When a Billion Chinese Jump (2 page)

Read When a Billion Chinese Jump Online

Authors: Jonathan Watts

Tags: #Political Science, #General, #Public Policy, #Environmental Policy

The environment had become a national security issue and the government started to respond. The leadership—the hydroengineer Hu Jintao and the geologist Wen Jiabao, or President Water and Premier Earth, as I came to think of them—started to shift the communist rhetoric from red to green. They wanted science to save nature. Instead of untrammeled economic expansion, they pledged sustainability. If their goals were achieved, China could emerge as the world’s first green superpower. Alternatively, if they failed and the world’s most populous nation continued to leap recklessly onward, our entire species could tip over the environmental precipice.

These were the extremes. The truth was probably somewhere in between—but where? That became the biggest question of my time in China. For the first five years as a news correspondent for the

Guardian,

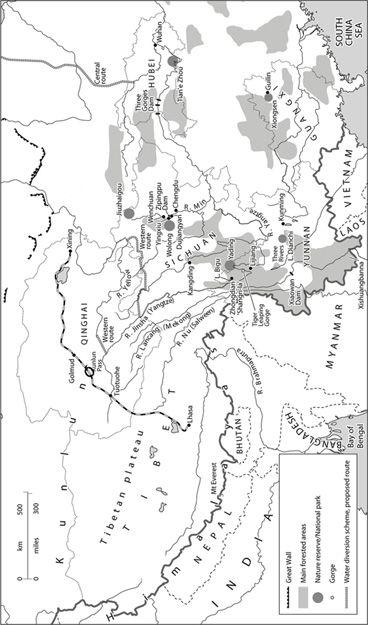

the environment was my primary concern. After that it became such an obsession that I took six months off for private research trips and then returned to a new post as Asia environment specialist. Traveling more than 100,000 miles from the mountains of Tibet to the deserts of Inner Mongolia, I witnessed environmental tragedies, consumer excess, and inspiring dedication. I went to Shangri-La and Xanadu, along the Silk Road, down coal mines, through dump sites, and into numerous cancer villages. I saw the richest community, the most polluted city, and the foulest sea. On the way I talked to leading conservationists, politicians, lawyers, authors, and China’s top experts on energy, glaciers, deserts, oceans, and the climate. Most compelling were the stories of ordinary people affected in extraordinary ways by a burst of human development and climate change the like of which the world had never seen before.

This, then, is a travelogue through a land obscured by smog and transformed by cranes; one that examines how rural environments are being affected by mass urban consumption. What are we losing and how? Where are the consequences? Can we fix them? It projects mankind’s modern development on a Chinese screen.

Though the chapters progress through regions and themes, the structure is polemical rather than geographic. When I had to choose between a strong case study and a line on the map, I opted for the former even if that occasionally meant leapfrogging provinces, returning to some places twice, and cutting across boundaries. Lest anyone fear that I am asserting a new territorial claim by Dongbei on Inner Mongolia, or by the southeast on Chongqing, I should state their place in these pages is determined by the powerful trends they illustrate. Similarly, my apologies to anyone who feels slighted or frustrated by my selective approach. Omission of a province is not intended to dismiss its importance any more than inclusion is meant to indicate a paradigm case.

The choice of location and topics in these pages is determined purely by my own experience. Even over many years and miles, that is limited. China is simply too vast and changing too fast to capture in its entirety. Starting from the world’s high, wild places and descending into the crowded polluted plains, the book tracks mankind’s modern development and my own growing realization: now China has jumped, we must all rebalance our lives.

Nature

Useless Trees

Shangri-La

A man with a beard is respected. The same applies to mountains. A person with a beard and hair is like a mountain covered with forest and grass. In the same vein, a mountain sheltered in forest and grass is like a person well clothed. A barren mountain is no different from a naked person, exposing its flesh and bone. An unsheltered mountain with poor soil painfully resembles a penniless and rugged man.

—Inscription on monument found in Yunnan, dated 1714

1

Paradise is no longer lost. According to the Chinese government, Shangri-La can be found at 28° north latitude, 99° east longitude, and an elevation of 3,300 meters at the foot of the Himalayas in northwest Yunnan Province. I started my journey at this self-proclaimed mountain idyll with the intention of working my way down and across China, tracking the progress of development on the way. Shangri-La seemed a fitting place to begin. Environmentalists considered it pristine, economists thought it backward. I planned to search here for natural and philosophical ideals, for untouched origins. But I may have arrived too late. Bumping along a dirt road through the mountains, I spied muddy hovels and forests spoiled by the blackened aftermath of logging teams. Gray drizzle doused a blaze of purple azaleas and white rhododendron shrubs. A track cut through a field of flowers to an alpine pool scarred on one side by the stumps of dozens of felled trees. The landscape, once one of the most stunning in China, had been violated.

For millennia, Bigu Lake in the heart of the region was protected by its remoteness. Although worshipped by local Tibetan communities, it was not mentioned in the extensive canons of Chinese literature. Government administrators and poetic wanderers rarely made it this far. It was too poor, too little known, too difficult to exploit.

All that changed in December 2001, when the Chinese authorities found a new way to sell northwest Yunnan’s beauty: they renamed the region Shangri-La. As well as being a brilliant piece of marketing, the appropriation of a fictional Utopia dreamed up seventy years earlier on the other side of the world was a remarkable act of chutzpah for a government that was, in theory at least, communist, atheist, and scientifically oriented.

The tourist trickle quickly became a flood. Road builders, dam makers, and hotel operators added to the height of the swell. Beauty was marketed as fantasy, often with disastrous consequences. When the Oscar-nominated filmmaker Chen Kaige wanted a spectacular location for a new kung fu blockbuster,

The Promise,

he came to Bigu Lake and completely reconfigured the idyllic landscape. With the enthusiastic support of the local government, the director’s team built a road through the field of azaleas, drove 100 piles into the lake for a bridge, and erected a five-story “Flower House” for the love scenes. Nobody took responsibility for the consequences.

2

After he ended shooting, the concrete-and-timber house was left dilapidated; the ground was strewn with plastic bags, polystyrene lunch boxes, and wine bottles. The lake was split in half by a bridge nobody needed. A temporary toilet and road besmirched the landscape, and locals demanded compensation for sheep that choked to death on the refuse.

I had come with one of the environmental activists who exposed the scandal and forced a cleanup. Zeren Pingcuo was a thickset Tibetan who worked as a nature photographer and conservationist. He was a man of few words, but what he said was usually to the point.

“Sacred places are no longer sacred,” he said, showing me before-and-after pictures of development in which lakesides and pastureland quickly filled with tourists, cars, and hotels.

He showed me older pictures of his Himalayan home: breathtaking scenes of hillsides decked with azaleas in spring, lush green valleys in summer, a forest in glorious autumn reds and golds, and mountain snowscapes in winter. There were intimate portraits of Naxi children and Tibetan monks, and lively scenes from monasteries, markets, and festivals. That

idyll had first been disturbed in the eighties and nineties by logging teams, then by tourism.

As our car climbed the steep mountain road, the destruction became more evident. Vast tracts of spruce forest were chopped and burned. The hillsides were filled with the blackened, stumpy corpses of trees and the withered brown saplings that were supposed to replace them but had failed to take.

“This all used to be virgin forest, but now it is an ecological war zone,” said Zeren. “The timber companies came here and cleared the hillsides.”

His home village of Jisha, which nestled in a high mountain valley, was suffering the results. He explained: “With less forest cover, there are fewer birds. With fewer birds there are more insects. And more insects means more damage to the crops.”

Although many locals believed their home was Shambala—a form of heaven on earth—Zeren was no romantic about the past. Before development, life for locals was tough and often short. But, even among his own people, the long-term trends disturbed him.

“Tibetans have lived in harmony with nature for hundreds of years. But now we consume in a decade what we used to use in a century.”

I too was here to get a taste of Shangri-La, albeit for work. I had come to look at beliefs. At the time, commentators in China complained their nation was mired in a grimy materialist mind-set that lacked an ideal of what a better world might look like. I wanted to see the alternatives. In such a diverse nation there were many: Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, nature worship, romantic escapism, and political utopianism. Shangri-La seemed as good a place as any to start.

But as I soon came to realize, searching for paradise was a complicated business, particularly when there were furiously competing claims to be the “real” Shangri-La. The word first appeared in the 1933 fantasy

Lost Horizon

by the British novelist James Hilton. After a crash landing on the Tibetan Plateau, the Western survivors stumble across the idyll of Shangri-La:

A strange and half-incredible sight … It was superb and exquisite. An austere emotion carried the eye upwards from milk-blue roofs to the gray rock bastion above … Beyond that, in a dazzling pyramid, soared the snow slopes of Karakal … the loveliest mountain on earth. (p. 66)

This resonated with visions of an earthly paradise found in other religions. The elements are remarkably consistent: fertility, diversity, color, tranquillity, and sparse, peaceful populations. These tropes form a baseline of sorts for man’s ideal view of the world. In economic terms, paradise is a place where natural supply exceeds human demand, where there is plenty of everything.

Hilton’s interwar fantasy was conceived not in southwest China but in northeast London, in Woodford Green, a Sunday afternoon’s drive away from my home in Barnet. Hilton never revealed the source of his inspiration, but the closest the author ever got to the Himalayan or Kunlun ranges was Pakistan. His descriptions of the mountain Utopia were widely—though probably not accurately—believed to be based on scientific studies and

National Geographic

reports about Yunnan by the eccentric U.S. botanist-adventurer Joseph Rock.

3

The Shangri-La myth of a land that could reseed human civilization after the planet was destroyed by war struck a chord in the 1930s, when development seemed geared only toward industrial destruction. After the award-winning Hollywood director Frank Capra released a film version in 1937, it became the ultimate escapist fantasy for a world on the brink of military conflict. Franklin D. Roosevelt named his newly converted presidential retreat in Maryland Shangri-La.

4

Hilton’s utopian dream was later transformed into a marketing gimmick. In 1992, Asia’s biggest luxury hotel group was founded in Hong Kong with the Shangri-La name. Market research suggested that the majority of Western tourists to Tibet and Nepal came seeking a Shangri-La experience.

5

China’s communist authorities started to take notice. Although the state had spent years dismissing Hilton’s fantasies as romantic nonsense, local governments suddenly began competing with one another to be recognized as Shangri-La. The fiercer the rivalry, the more distorted the utopian ideal became.

I headed to Lijiang, Joseph Rock’s base from 1922 to 1949. Like all of northwest Yunnan, the setting was idyllic. In the old town, traditional wood buildings sloped up the hillside, the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain towered in the distance, and the streets thronged with a colorful ethnic mix. The city was historically rich. Kublai Khan’s troops crossed the river here. The Red Army passed through on their Long March. For decades, the spectacular setting, Naxi-minority architecture, and canal-lined

streets attracted artists, writers, and adventurers. After 1996, when it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it became a fixture on the banana-pancake trail of foreign backpackers.

6

After the rebranding of northwest Yunnan as Shangri-La, this swelled into a wave of domestic travelers.

7