When a Billion Chinese Jump (15 page)

Read When a Billion Chinese Jump Online

Authors: Jonathan Watts

Tags: #Political Science, #General, #Public Policy, #Environmental Policy

Yet the story never made the front pages. Tragic as the news was, the baiji was just the latest species on the eco-scrap heap. Nobody felt affected. Nobody felt personally responsible. The West blamed China.

China blamed illegal behavior. Everyone blamed economic development, but who wanted to sacrifice that for a dolphin with squinty eyes?

Growth, it seemed, had a price. Modernization was messy. The development model—pioneered in the UK, then Europe, North America, and Japan—was to get rich first, clean up later. Sometimes, as in the case of the baiji, the fix came too late, but the idea of progress was based on the assumption that humanity would eventually get it right. According to this view, the left-behind flag bearer was just an unfortunate casualty of development.

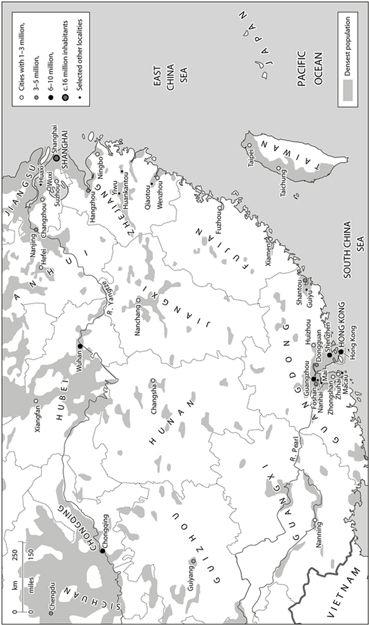

But I was no longer convinced by such reassurances. Progress no longer sounded quite so admirable. I would travel farther along the trajectory of modernization to look in more detail at where it was taking us, and why. The drivers of development could be found on the fast-evolving coast of the southeast. Perhaps at my next destination, Guangdong Province, I would discover how the export of blame, waste, and responsibility had become one of the dirtiest businesses of globalization. The rules and regulations intended to curb this weren’t working, but what did this have to do with the rest of us?

Man

Made in China?

Guangdong

Guangdong is where China and your life intersect.

—Alexandra Harney

1

The children at Mai Middle School had probably never heard of Tesco and they could only imagine the luxuries offered by Britain’s biggest supermarket chain. But though their village was five thousand miles away from the nearest UK High Street, they could see, feel, and smell the consequences of globalized consumer culture.

On a tree near their classrooms, a snagged blue-and-white Tesco shopping bag fluttered in the warm semitropical breeze like the flag of a distant empire. The gates of a neighboring factory were decorated with huge plastic banners advertising a discount that would be worth a week’s wages in Mai: “£20 Off Tesco Mobile Phones If You Spend More Than £40 in the Store.” The stream beside their school was choked with carrier bags and plastic wrappers from the other side of the world. Staring up from the fetid water and filthy banks were logos for Tesco, Wal-Mart, Argos, and even Help the Aged. A bold mission statement on the charity shop’s green-and-white bag vowed to fight “Poverty, Isolation and Neglect.”

It was a decent sentiment, I thought, as I stood in the midst of the illegally dumped garbage. I could imagine my mother feeling good filling a shopping bag like that with secondhand clothes. She would think her shopping was making the world a better place; that it was a form of recycling that helped the aged and the planet at the same time. It would

upset her to think people on the other side of the world were paying an environmental price for her charity.

Nobody in Mai was asking for handouts, though the average income was considerably less than Britain’s state pension. Locals wanted something far more basic: clean air and water.

“The river is foul—we can smell it from our classrooms,” Wang Yanxia, a pupil at the middle school, told me during a noisy breaktime. “When it rains, the water floods onto the path and the stench is everywhere.”

Her friend Cui Yun said it had been like this since she had entered the school three years earlier. “My mother worries about my health. Lots of people get sick.”

The school was on a street full of small recycling firms that served as the intestine of the global economy, breaking down the world’s discarded plastic bags, bottles, and wrappers into tiny reusable parts. Most of the firms were little bigger than sheds, outside which stood blackboards detailing the type, color, and quality of the plastic they dealt in. Migrant workers from Anhui, Sichuan, and Guangxi sifted by hand through hundreds of thousands of tiny plastic pellets, picking out discolored flecks and bits of fluff. The recycled plastic was suitable only for weaving into low-grade sheeting, such as the ubiquitous red-white-and-blue coverings on building sites and the cheap carryalls used by migrants when they travel. One of the traders told me she bought semiprocessed bags for 9,000 yuan a ton (around $1,286) and, after painstakingly cleaning up the contents, sold the plastic for 10,500 yuan.

The cost was ditches full of garbage and a population full of health concerns. The village doctor said the area had an unusually high incidence of respiratory diseases that might be attributable to pollution. But he said locals were willing to pay the price. “This is a sensitive topic. Of course we want a gardenlike environment, but people here have to make a living.” A migrant laborer who was walking past the filthy stream agreed. “I don’t care about the environment. If your stomach isn’t full, how can you worry about your health?”

I was in Guangdong to examine the environmental price China had paid since opening up to global capital and markets. In 1979, this southeastern province was the first to trade with the outside world, and it had since become one of the richest regions in China. Much of its wealth was generated by regurgitating the muck of the global economy either in

the form of garbage for recycling or outsourced dirty manufacturing. Fittingly for our globalized age, it was part economic miracle, part environmental tragedy. This was where most of the planet’s toys and shoes were made, where Apple outsourced much of the production of its iPods, where Wal-Mart filled its shelves, where Britain’s shoes and America’s toys and everyone’s Christmas decorations were made. Since the start of China’s economic reforms in 1978, Guangdong’s economy had grown more than a hundredfold to the point where it was bigger than that of Turkey, South America, and Finland.

2

If it were a country, it could join the G20 of the world’s richest nations. It was also home to many of the dirtiest and most polluted places on the mainland. The expression “filthy rich” could have been made for Guangdong.

My intention was to sift through the province’s rubbish dumps to see where the filth came from. It was a muckraking exercise in both senses, a very deliberate search for the dark and dirty side of development, both in China and overseas. Digging for dirt is as much a part of a reporter’s role as reflecting background trends and describing the details of everyday life. Getting a balance between these elements is one of the biggest challenges of the job. To have any chance of achieving that, it is necessary to get out of the office and into the field. Stories rarely turn out as expected.

There was no shortage of places to investigate in Guangdong. Among the palm trees and factories of this semitropical manufacturing region were clusters of contemporary

Sanford & Son

businesses that dealt with

yang laji,

or foreign rubbish. Shopping bags and bottles were shipped to Shunde and Heshan from London, Rotterdam, and Hong Kong for chopping, melting, and remolding into pellets. In the electronic waste communities of Guiyu and Qingyuan, old computers, televisions, and home appliances from the United States, Japan, and South Korea were stripped down and broken up. On a bigger scale in Dongguang, Zhang Yin’s waste-paper empire has made her the richest self-made woman in the world, overtaking Oprah Winfrey and J. K. Rowling.

3

There seemed to be little stigma attached to waste. As I left Mai, my driver told me he was grateful for the foreign garbage. “In Guangdong, when we call someone a rubbish man, it’s a compliment,” he told me. “It means they have money.”

On a long, flat gray road, we passed the gates and buildings of countless factories and industrial parks, most of them joint ventures with foreign

investors. Major international brands had home appliances, textiles, shoes, furniture, plastic bags, toys, and knickknacks manufactured and packaged far more cheaply here than in their home countries. When the goods were sold overseas, most of the profit went to the foreign brand owner and the retailer. A tiny share of the revenue remained in Guangdong, though the original product and its wrapping often made its way back here after it was used and discarded in the West.

After an hour’s drive, we reached the outskirts of Shunde, where the compressed bales of Dutch Kinder Eggs, Italian diapers, French Lego, and other European trash were stacked on the roadside. Reflecting the close proximity of Hong Kong and its British legacy, much of it was from the UK—Tesco milk cartons, Marks & Spencer’s cranberry juice, Kellogg’s cornflakes boxes, Walkers crisp packets, Snickers wrappers, and Persil powder containers. It was not just a compression of paper and plastic but of marketing slogans: “They’re G-r-r-reat!” “Aah! Bisto,” “Whiter Than White.”

In trade terms, it made perfect sense for the waste to be shipped across the world for recycling. Historically, British and other foreign merchants had always found it easy to fill their ships with goods on the route from China, but they often sailed in the opposite direction with empty cargo holds. When the economist and demographer Thomas Malthus foresaw the rise of Chinese manufacturing in his 1798

Essay on the Principle of Population,

he correctly predicted that this would lead to a trade imbalance because Britain would have little to offer in return. The gap, he said, would have to be made up with “luxuries collected from around the world.”

What that meant in practice was that my country became the world’s biggest drug dealer. British and Dutch merchants had already begun selling Indian-grown opium in Guangdong, then known as Canton, which was at the time the only open trading port in China. In the twenty years up to 1839, imports of this “luxury” narcotic surged fivefold, prompting the Qing emperor to impose a ban. The British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, responded as any self-respecting underworld boss would do by using force to protect and expand his business.

4

Using coal-powered gunboats for the first time, the Royal Navy seized Hong Kong, blockaded the Pearl River, sank dozens of Chinese ships, and forced the Qing emperor to open up Shanghai and several other ports to foreign trade. For China, the crushing defeat in the First Opium War was a rude introduction to carbon-capital power. The ancient civilization never entirely recovered from the shock.

At the time of my visit, there was once again a huge trade imbalance. But this time, the shortfall was being made up not by drugs but by garbage.

5

The economics were logical. It was cheaper to send a container of waste from London to Guangdong on an otherwise empty ship than it was to truck it to Manchester.

6

Adam Smith, the father of capitalism, would probably have considered this business as usual. In the eighteenth century, he described how China’s poor were so wretched they ate rubbish: “They are eager to fish up the nastiest garbage thrown overboard from any European ship. Any carrion, the carcase of a dead dog or cat, for example, is as welcome to them as the most wholesome food to the people of other countries.”

7

But sending waste to the other side of the world was fraught with environmental, health, and ethical hazards. Although recycling could save more carbon emissions than simply dumping the waste in a landfill, the rubbish shipments put an irresponsible distance between consumption and its consequences.

8

People in other countries were being exposed to risks and pollution that wealthy foreign consumers were not willing to accept themselves.

The garbage had been building up for decades. In the mid-sixties, the philosopher Alan Watts was among the first to anticipate a global waste crisis as he contemplated the incipient consumer culture of the United States and western Europe: “Can any melting or burning imaginable get rid of these ever-rising mountains of ruin—especially when the things we make and build are beginning to look more and more like rubbish even before they are thrown away?”

9

Since then, landfill sites in Europe, North America, and Japan have been filling up almost as fast as they were dug. The alternatives were not much better. Incinerators might reduce rubbish to ash, but, unless operated at very high temperatures, they foul the air with dioxins and other toxins. Meanwhile, we—the global consumer class—were buying ever more goods in ever more layers of wrapping.