When a Billion Chinese Jump (37 page)

Read When a Billion Chinese Jump Online

Authors: Jonathan Watts

Tags: #Political Science, #General, #Public Policy, #Environmental Policy

People were increasingly drawn to Urumqi because it was becoming the center of oil and gas production in central Asia.

31

The old Silk Road had been reinforced with pipelines, railways, and highways.

32

Driving back along the road from the glacier to the regional capital, the dominance of the high-carbon economy was evident in cooling towers, smokestacks, oil drums, and gas pipes.

On the outskirts of the city, massive refineries, vast storage drums, and a tangle of pipes marked the presence of the world’s first trillion-dollar company, PetroChina.

33

With overseas partners, this state-run firm populated the Turpan and Tarim basins with

ketouji

(lit., “kowtowing machines”), the “nodding donkeys” that bow back and forth hypnotically as they pump millions of tons of oil from under the sand.

Viewed from Urumqi, the government’s “Go West” campaign to redistribute wealth to poorer inland regions looks more like a “Take East” extraction of energy resources. The flow of oil from the desert and melt-water from the mountains has created a boomtown, but most of the new money has been sucked up by Han settlers.

In the 1950s, Urumqi was a gritty sprawl of 100,000 Uighurs living in two-or three-story mud-brick homes arranged in narrow sand-colored curling alleyways. Poverty was so widespread and health care so rudimentary that people would count themselves lucky to live beyond forty years of age. Traveling here in the 1930s, the English missionary Mildred Cable uncharitably described it as a place possessing “no beauty, no style, no dignity.”

34

Similar terms could be used in the modern age, but for a very different cityscape. As the local economy tore along at a 20–30 percent annual growth rate, Urumqi extended farther across the plains and up into the sky, sucking up water supplies along the way. As the Han settlers poured in, Uighur alleyways gave way to six-lane city streets, square high-rises, and concrete squares. Among the big new water-guzzling developments are the Snow Lotus Mountain Golf Club and the Silk Road International Ski Resort.

35

The thirst of these luxury sports facilities is slaked by the extra runoff from Urumqi Number One and the 154 other glaciers that feed the river basin. The melt doubled in the twenty years after 1985 and is likely to continue rising for several decades. After that, if the glaciologists are right, Urumqi is at risk of evaporating along with its water supply.

The central government has long been aware of the risks, but it is only in recent years that it has identified the planetary causes. In 2007, it issued the country’s first national plan on climate change, spelling out policies for afforestation, recyclable energy development, and a raft of other countermeasures nationwide. Xinjiang’s planners have also realized that they need to find somewhere other than golf greens and artificial pistes to invest their water bonanza. They built an eco-park to promote a more sustainable lifestyle among residents, announced plans to build fifty-nine reservoirs to catch glacier meltwater, and were considering augmenting this with subterranean storage pools.

36

But a still more radical plan was also under consideration. To explore it fully, Premier Wen Jiabao dispatched a special envoy with a reputation for earthshakingly ambitious ideas.

Qian Zhengying was very short, very old, and extremely controversial. A former minister of water conservancy and power, she had been in the senior ranks of government throughout the Great Leap Forward. Even after retirement she was a driving force in the Three Gorges Dam project. Few politicians generated such a mix of hatred and respect.

37

We met for an interview shortly after she had finished a fact-finding tour of Turpan. She had been there to see if Xinjiang’s rich coal seams could be exploited. But what she found was China’s worst water problem. “We studied every glacier. Because of global warming, we found the small glaciers are melting quickly. So until 2020 the water in the rivers may well

increase, but what happens after that when the meltwater is gone?” asked the tiny, wizened figure who managed to fill a giant government chamber with her presence.

As a quarter of the region’s water was supplied by glaciers, she said it was vital that the bonus meltwater be used wisely. “We have to be responsible for future generations so we should not start developing at a time when the water income is unusually large. Because later, when water declines, we won’t have enough to sustain things.”

She had advised Premier Wen that the priority was to restore dried-up lakes, depleted aquifers, and other environmental damage wrought in the past. To do this, she said, farmers should be paid to cease irrigation of their fields because so much water was wasted.

“In Xinjiang, close to 96 percent of the water is used for agriculture. This is the highest share in the world,” Qian told me. “This has already caused the destruction of the freshwater ecosystem. In some lower reaches of rivers, there is no longer any water. Some wetlands and lakes have degraded and in some areas the water is severely overused.”

I was stunned by her admission that the dash to transform desert into farmland over the past forty years had resulted in a massive waste of water resources and environmental damage. This was an incredible volte-face for the Maoist who had been part of a government that urged Han Chinese pioneers to cultivate Xinjiang and ease the country’s food shortages.

Now she wanted to shift farmers off the land and into the cities to raise the efficiency of water utilization. Compared with the relocation program needed for her previous megaprojects, Qian predicted the demographic reengineering would be straightforward. “For the Three Gorges project, moving one person cost 40,000 yuan and it was complicated. In Xinjiang, all that is required is to move people very close to cities and provide them with housing. It will be easier.”

That was a dangerous assumption. Water, heat, and migration were a volatile mix. Many Uighurs already felt they were being driven out of a homeland degraded by overcultivation and increasingly fraught with ethnic tension.

38

Both were growing worse. In July 2009, the worst day of racial violence in modern Chinese history left 197 dead and 1,721 injured.

39

The vast majority of the victims were Han settlers. In the future, a changing climate is likely to add to the tension as it forces more people to migrate and increases competition for water and food supplies.

Qian’s more immediate concern was the economy. The uncertainties of climate change were making it more difficult to allocate water resources in China. Huge reservoirs she had helped to design near Beijing and Tianjin were getting barely more than a third of the expected runoff.

40

In northern China, she said, the accumulated water deficit was 9 billion cubic meters, which had led to massive depletion of aquifers. Xinjiang’s melting glaciers and overused rivers were a particular headache. Instead of trying to feed the nation, Qian said, the region should just grow enough for itself. “In the past, the government officials in Xinjiang were very kind. They felt the country had a food-security problem, so they wanted to produce an agricultural surplus. But now, given Xinjiang’s water problem, they should only be required to supply sufficient food for their own use.”

Her comments did not mark a late-life conversion to Taoism. Qian’s conclusions were based in true Marxist style on economic productivity. Despite the expansion of farming and the mass diversion of water over the past fifty years, Xinjiang’s agricultural output remained modest relative to its size.

41

The former minister, who had made a career out of diverting rivers from one area to another, felt the water would be more efficiently allocated to industry and to one sector in particular: coal mining.

“The Turpan area has rich coal deposits but they don’t have the water to develop them,” she said. “Our study concludes that we should divert some of the water that has been used until now for agriculture.”

The diversion of Xinjiang’s water from oxygen-producing crops to carbon-emitting fuel is a terrifying prospect for a world already worried about food shortages and global warming, But Qian’s vision is in line with China’s strategic goals. Economic growth must not be allowed to slow down despite growing concern about climate change. This outlook underlies all of its actions. Ahead of international climate talks in Copenhagen in 2009, the government set its first carbon target. It was an important step, but the intensity goal was a promise to slow the growth of emissions rather than to cut them. Until at least 2030, China expects to be the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gas.

More and more of it will come from Xinjiang, which contains 40 percent of the country’s known coal reserves. They have not been exploited until now because of the difficulties of extraction and the cost of transport. But engineers plan to turn that coal into gas or liquid so it can be pumped east through pipelines. The region, which is already feeling many of the

most dramatic effects of climate change, is on course to become one of the biggest sources of carbon entering the world’s atmosphere.

42

Miners and power companies are completing the mission the glacier melters abandoned fifty years earlier. Instead of sprinkling coal dust on the ice, they pump carbon into the air. As Urumqi Number One shows, this is alarmingly effective. Long after we stopped trying, mankind has mastered glacier melting. Unfortunately, when it comes to putting ice back on the mountains, we still do not have the first idea.

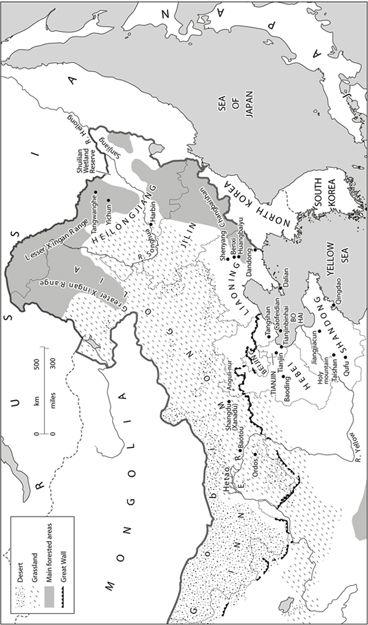

In Xinjiang the evidence of climate change and environmental degradation is undeniable, but that is at least a spur for action. Policymakers have started to realize that the current path of economic growth leads toward a dead end. Even Madame Qian is talking about ecological restoration. Elsewhere in China too, scientists and entrepreneurs are looking for climate solutions and profits. Architects, engineers, and urban planners are trying to find a technological substitute to the hydrocarbon economy. Civil society activists are promoting a more sustainable lifestyle. The Scientific Outlook on Development espoused by President Water and Premier Earth aims to create an eco-civilization. But how much progress has China made toward an alternative model of development? In search of an answer I headed to Dongbei, the northeast, to assess the country’s capacity for reinvention.

Alternatives

Science versus Math

Tianjin, Hebei, and Liaoning

China is a country where once they realize, “Gee, we have to do

something,” then they leap forward.

—Suntech founder Shi Zhengrong, the world’s first solar billionaire

The egghead leading China’s charge toward an efficient, low-carbon future almost never made it to university. Professor Li Can grew up during the Cultural Revolution with a politically unfortunate habit: he loved to study. This went down well with his high school teachers, but, in those days, it was not much good being a top-level student if you were a second-rate revolutionary.

By 1975, the nation’s universities had been closed for almost a decade. Business was still frowned upon. For a bright young man, the only career tracks were through the Communist Party or the government. Lacking the ideological zeal for either, Li’s only choice after graduation was to return to his home in a remote corner of Gansu and become a barefoot doctor. His high school education was all the qualification he needed to perform acupuncture and rudimentary medicine around local villages near the old Silk Road.

This was a period of massive transition for China, but the changes almost passed Li by. After Mao died, a new leadership took over. Soon after, they announced the full reopening of the universities. Li did not hear about it for weeks because nobody in his village had a telephone or a radio.

Fortunately, the deputy headmaster of his old school remembered the

brilliant pupil who had been forced to return to the desert, He cycled 30 kilometers to Li’s home to tell him the news and recommended he join the first wave of students to take the Gaokao entrance exam. There was barely any time to prepare and few teaching materials. In those conditions, the future head of China’s clean energy research lab did well to come forty-ninth out of 150 students in his region. None of the prestigious universities would accept him. Desperate to secure a place, he applied for a course at a second-rate university in a field he had little interest in.