Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (35 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

From the beginning of the campaign for nomination, Humphrey was in trouble. For three years, despite private misgivings, he had publicly supported administration policies in Vietnam. If he continued to back the idea of military victory, he would not enjoy any support from insurgent Democrats ready to split the party in two. But if he made public his personal opposition to escalation, he risked Lyndon Johnson’s wrath. Johnson no longer had the power to designate his successor, but he could veto Humphrey. In any event, as the campaign developed Humphrey would come to be defined as the surrogate for the president who had taken pleasure in despising him.

Further roiling the Democratic party were peace negotiations with the Vietnamese communists, now at last under way. The talks began in Paris on May 13, 1968. W. Averell Harriman represented the United States. North Vietnam sent Xuan Thuy. One of the earliest anti-French Vietnamese nationalists, Thuy had spent years in French prisons. Between 1963 and 1965 he served as foreign minister of North Vietnam. Nguyen Thi Binh represented the National Liberation Front, the political arm of the Vietcong. She had been a strident student nationalist, imprisoned between 1951 and 1954. She joined the National Liberation Front in 1960 and was soon traveling the world promoting Vietcong goals, a political journey that had now taken her to Paris. South Vietnam sent Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky to head its delegation.

Saigon was in no mood to compromise. Any accommodation with the communists, the South Vietnamese leaders knew, would eventually send them to labor camps or worse. The United States approached the talks believing it held the advantage in Vietnam, while the North Vietnamese were just as certain that the Americans had suffered a strategic defeat. From the beginning Johnson insisted that Harriman take the hard line: Leave the Thieu-Ky government in place, deny representation for the National Liberation Front, implement mutual withdrawal of all North Vietnamese and American troops, and exchange prisoners of war. Xuan Thuy, just as adamantly, articulated the North Vietnamese position: Cease all bombing raids over North Vietnam, withdraw all American troops from South Vietnam, remove the Thieu-Ky government, and create a coalition government in Saigon that included the National Liberation Front.

The American delegation spent the first few weeks quartered in the plush fifth floor of the Crillon Hotel, but after a few meetings with Xuan Thuy, the delegates moved down to the cheaper first floor and brought their wives from Washington. It was going to be a long stay. Throughout 1968 the impasse found expression in a debate over the size and shape of the negotiating table. Ky refused to sit at the same table with Nguyen Thi Binh, especially if her place indicated equal status with him. Binh, of course, insisted on equal status. Harriman had to think of a table design that would satisfy both. The world press corps descended on Paris to report the talks but ended up taking pictures again and again of the table. Art Buchwald observed that once they finished the six-month debate over the shape of the table, the diplomats would have all of 1969 to decide on “butcher block, Formica, or wood finish.”

Harriman considered Nguyen Cao Ky an impossible, petulant hack who made the communists look like paragons. One member of the American delegation drew a laugh out of Harriman when he suggested that they solve the problem of the size and shape of the table by using “different size chairs, with the baby’s high chair reserved for Ky.” More than one observer noted that during debate about the table, 8,000 Americans died along with 50,000 North Vietnamese and perhaps another 50,000 South Vietnamese civilians. Throughout 1968 the Paris peace talks spent their energies in pointless procedural arguments, deepening the cynicism with which Americans viewed the war.

The presidential candidates running against the war made the most of the stalled negotiations.

Senator Robert Kennedy of Boston, Humphrey’s strongest opponent, was then in his mid-forties. Kennedy had graduated from Harvard and from the University of Virginia Law School. He masterminded his brother’s successful 1960 bid for the presidency and then became attorney general. Robert Kennedy was a man of intense passion and brutal honesty. Tact was not his strong suit. Joseph Kennedy, the patriarch of the family, who considered John too forgiving of other people, said of Bobby that “when he hates you, you stay hated.” After his brother’s assassination, Kennedy served as attorney general for a few more months, but his dislike for Lyndon Johnson was matched only by Johnson’s loathing for him. Much in agreement in their domestic-policy liberalism, they were nevertheless hopelessly divided in personality, the newly genteel Irish wealth of Massachusetts against the earthy poverty of the Hill Country. Kennedy left the Justice Department in 1964 and won a United States Senate seat from New York.

After the assassination, Robert Kennedy was a different man. Well before, he had lost his cockiness and became introspective, reading deeply in philosophy, tragedy, and religion. He questioned the existence of God in a world that killed the innocent. Moved by the writings of Albert Camus, he wrote in his notebook, “Perhaps we cannot prevent this world from being a world in which children are tortured, but we can reduce the number of tortured children.” By 1966 he was concluding that the war had gotten out of control, that the United States was seeking a military solution to a political problem. “I have tried in vain to alter our course in Vietnam before it further saps our spirit and our manpower, further raises the risks of a wider war, and further destroys the country and the people it was meant to save,” he said on March 26, 1968, in his announcement for the presidency. His campaign was an immediate success. The Kennedy mystique was a powerful force in 1968, as were Kennedy money and ties to the party machine. Eugene McCarthy commanded the respect of the antiwar movement, but its heart was with Kennedy. Kennedy defeated McCarthy in the California primary in June, but on the night of his victory he was assassinated in Los Angeles. His death put the nomination in the hands of Humphrey, who had gathered delegates from states where the party establishment rather than the voters made the selection. The Democrats then headed for their national convention in Chicago.

The Republican campaign was also fixing on the war. Nelson Rockefeller, heir to the Standard Oil fortune and governor of New York, hoped for the GOP nomination. But Republican conservatives hated him, not only for his moderate liberalism but for his clear distaste for the nomination of Barry Goldwater in the election of 1964. Governor George Romney of Michigan, a former president of American Motors, was another liberal Republican. Although GOP conservatives rejected many of Romney’s positions, they did not detest him as they did Rockefeller. But Romney made one devastating rhetorical slip. During the New Hampshire primary campaign in late February, he confessed to having been “brainwashed” by MACV during a visit to Vietnam in which he was assured of the war’s progress. Politicians cannot speak of themselves with so naïve and simple an openness. Romney lost the New Hampshire primary. Out of the squabblings among the Republicans emerged Richard M. Nixon.

Between 1953 and 1961 Nixon had served as vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower. After losing the 1960 presidential election to John F. Kennedy and suffering another loss in the 1962 California gubernatorial election, he practiced law and spoke on behalf of Republican candidates, building up a long list of political IOUs that he called in during the 1968 election. In the vaguest terms, Nixon criticized Johnson’s conduct of the war and promised that he could do better. On the eve of the New Hampshire primary he made his “pledge to [the voters] that new leadership will end the war and win the peace in the Pacific.” When Humphrey demanded that he spell out his peace plan, Nixon responded, “No one with this responsibility who is seeking office should give away any of his bargaining position in advance . . . . Under no circumstances should a man say what he would do next January.” The remark did not awaken the skepticism it came close to inviting. Nixon easily won the nomination.

Neither Nixon’s vague peace plans nor Humphrey’s equally vague promises satisfied the nation’s young peace activists. For three years their calls for an end to the war had increased in stridency. Government officials and agents ignored their demands, infiltrated their organizations, and expressed contempt for their political and cultural style. For a brief time some saw a glimmer of hope in Eugene McCarthy and Bobby Kennedy. But McCarthy seemed almost determined to distance himself from the public he was soliciting, and Kennedy was dead. At his funeral Tom Hayden, a leader of SDS, wept. Across the country other students shared his grief. “As I look back on the 60s,” mused Michael Harrington, whose writings a few years earlier had brought poverty back to the attention of Americans basking in the prosperity following World War II, Robert Kennedy “was the man who actually could have changed the course of American history.”

The passing of Kennedy deprived young protesters of their only powerful political voice. He might have been elected president. He might have made a difference. The remaining politicians were establishment figures who cared little for the dreams of the young. To register their protests—to voice their disenchantment with the political process that was excluding them—members of various student organizations decided to go to the National Democratic Convention in Chicago. Some represented factions of the New Left. Many were committed Marxists, wedded to revolutionary change. Others were apostles of the counterculture whose politics were as nebulous as their religious beliefs. The only conviction they shared was the notion that liberal politics were moribund.

The establishment Democrats should have known what was in store. When Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in April 1968, racial rebellion broke out in the nation’s cities. Late in April, when Columbia University’s president Grayson Kirk held a memorial service for King, the local SDS disrupted the gathering, accusing Columbia of being insensitive to the needs of black people and of supporting the Vietnam War through its membership in the Institute for Defense Analysis. As anger swept the university, students occupied several buildings on campus, including Kirk’s office, and pictures of them smoking his cigars and drinking his sherry made all the wire services. The dispute went on for three weeks before New York City police forcibly cleared the campus.

The protest movement then shifted to Chicago. Orthodox urban politicians there as throughout the country cared little for the creeds of the New Left and the politically outrageous. Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley mobilized 12,000 police and prepared to call out national guardsmen. He denied demonstrators the right to protest or march. Short, barrel-chested, with the jowls of a big city boss, Daley promised that he would not allow any “long-haired punks” to dirty the city where he attended mass every day and decent people lived. The novelist Norman Mailer caught Daley’s disdain for the eastern press and the counterculture: “No interlopers for any network of Jew-Wasp media men were going to dominate the streets of his parochial city, nor none of their crypto-accomplices with long hair, sexual liberty, drug license and unbridled mouths.”

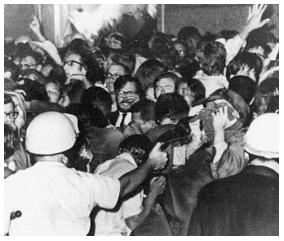

Given Daley’s attitude and the determination of the protesters, violence was certain. The Youth International party, or Yippies, led by Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, urged people to “vote Pig in’68.” They nominated their own candidate—“Pigasus,” a fat pig they paraded through the streets. They demanded legalization of marijuana and “all other psychedelic drugs,” an “end to all censorship,” total disarmament of all people “beginning with the police,” and abolition of money and work. “We believe,” Point 15 of their manifesto stated, “that people should fuck all the time, anytime, whomever they wish.” Such appeals were not part of the establishment’s vision of a better nation, and it was emphatically not Mayor Daley’s. Police repeatedly clashed with the demonstrators. They fired tear gas into groups of protesters. “We walked along,” as Sol Lerner of the

Village Voice

would remember it, “hands outstretched, bumping into people and trees, tears dripping from our eyes and mucus smeared across our faces.” The police, armed with clubs, waded into the demonstrators, one of whom “saw a cop hit a guy over the head and the club break. I turned to the left and saw another cop jab the guy right in the kidneys.” Demonstrators fought back, threw rocks, overturned cars, set trash cans on fire. Reporters and photographers became victims of what was later termed a “police riot.” Nicholas von Hoffman of the

Wash

ington Post

reported police attacks on news photographers: “Pictures are unanswerable evidence in court. [The police had] taken off their badges, their name plates, even the unit patches on their shoulders to become a mob of identical, unidentifiable club swingers.” But the television cameras did not blink, and the violence became entertainment in millions of homes. Disgusted by the police, Walter Cronkite told his prime-time viewers, “I want to pack my bags and get out of this city.”