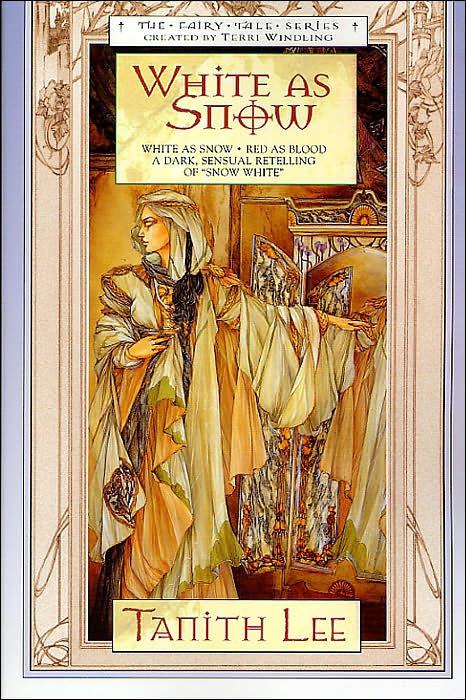

White As Snow (Fairy Tale)

Read White As Snow (Fairy Tale) Online

Authors: Tanith Lee

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

The author would like to extend most grateful thanks to Barbara Levick, of St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, for her invaluable help and enlightenment on the Latin fringes of this book.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Tor Copyright Notice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

BOOK ONE

-

Tam Atra Quam Ebenus Black as Ebony

Tor Copyright Notice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

BOOK ONE

-

Tam Atra Quam Ebenus Black as Ebony

by Terri Windling

Once upon a time fairy tales were told to audiences of young and old alike. It is only in the last century that such tales were deemed fit only for small children, stripped of much of their original complexity, sensuality, and power to frighten and delight. In the Fairy Tale series, some of the finest writers working today are going back to the older versions of tales and reclaiming them for adult readers, reworking their themes into original, highly unusual fantasy novels.

This series began many years ago, when artist Thomas Canty and I asked some of our favorite writers if they would create new novels based on old tales, each one to be published with Tom’s distinctive, Pre-Raphaelite-inspired cover art. The writers were free to approach the tales in any way they liked, and so some recast the stories in the modern settings, while others used historical landscapes or created enchanted imaginary worlds. The first volumes in the series (originally published by Ace Books) were

The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars

by Steven Brust;

Jack the Giant-killer

(later expanded into

Jack of Kinrowan

) by Charles

de Lint; and

The Nightingale

by Kara Dalkey. The series then moved to its present home at Tor Books, where we’ve published

Snow White and Rose Red

by Patricia C. Wrede;

Tam Lin

by Pamela Dean; and

Briar Rose

by Jane Yolen.

The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars

by Steven Brust;

Jack the Giant-killer

(later expanded into

Jack of Kinrowan

) by Charles

de Lint; and

The Nightingale

by Kara Dalkey. The series then moved to its present home at Tor Books, where we’ve published

Snow White and Rose Red

by Patricia C. Wrede;

Tam Lin

by Pamela Dean; and

Briar Rose

by Jane Yolen.

Now, after a long hiatus (during which we produced six volumes of adult fairy tale short stories in the

Snow White, Blood Red

series, co-edited with Ellen Datlow), we’re back to offer more fairy tale novels, beginning with a splendid retelling of Snow White by a modern master of the form: English writer Tanith Lee. We’re particularly pleased to welcome Tanith into this series because she’s one of the first writers in the fantasy field to work extensively with fairy tale material, in her groundbreaking collection of stories

Red as Blood: Tales from the Sisters Grimmer

(1983). Lee has been called “the Angela Carter of fantasy literature”—and like Carter, her approach to fairy tales is very dark, sensual, and thoroughly steeped in the folklore tradition. She has worked with the Snow White theme twice before, in her haunting short stories “Red as Blood” and “Snow-Drop.” Now she takes a very different approach in a brutal, mystical version of the story invoking the Demeter-Persephone myth and old pagan religions of the forest.

Snow White, Blood Red

series, co-edited with Ellen Datlow), we’re back to offer more fairy tale novels, beginning with a splendid retelling of Snow White by a modern master of the form: English writer Tanith Lee. We’re particularly pleased to welcome Tanith into this series because she’s one of the first writers in the fantasy field to work extensively with fairy tale material, in her groundbreaking collection of stories

Red as Blood: Tales from the Sisters Grimmer

(1983). Lee has been called “the Angela Carter of fantasy literature”—and like Carter, her approach to fairy tales is very dark, sensual, and thoroughly steeped in the folklore tradition. She has worked with the Snow White theme twice before, in her haunting short stories “Red as Blood” and “Snow-Drop.” Now she takes a very different approach in a brutal, mystical version of the story invoking the Demeter-Persephone myth and old pagan religions of the forest.

To most people today, the name Snow White evokes visions of dwarves whistling as they work, and a wide-eyed, fluttery princess singing, “Some day my prince will come.” (A friend of mine claims this song is responsible for the problems of a whole generation of American women.) Yet the Snow White theme is one of the darkest and strangest to be found in the fairy tale canon—a chilling tale of murderous rivalry, adolescent sexual ripening, poisoned gifts, blood on snow, witchcraft, and ritual cannibalism … in short, not a tale originally intended for children’s tender ears.

Disney’s well-known film version of the story, released in 1937, was ostensibly based on the German tale popularized by the Brothers Grimm. Originally titled “Snow-drop” and published in

Kinder- und Hausmärchen

in 1812, the Grimms’ “Snow

White” is a darker, chillier story than the musical Disney cartoon, yet it too had been cleaned up for publication, edited to emphasize the good Protestant values held by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Although legend has them roaming the countryside collecting stories from stout German peasants, in truth the Grimm brothers acquired most of their tales from a middle-class circle of friends, who in turn were recounting tales learned from nurses, governesses, and servants, not all of them German. Thus the “German folktales” published by the Grimms included those from the oral folk traditions of other countries, and were also influenced by the literary fairy tales of writers like Straparola, Basile, D’Aulnoy, and Perrault in Italy and France.

Kinder- und Hausmärchen

in 1812, the Grimms’ “Snow

White” is a darker, chillier story than the musical Disney cartoon, yet it too had been cleaned up for publication, edited to emphasize the good Protestant values held by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Although legend has them roaming the countryside collecting stories from stout German peasants, in truth the Grimm brothers acquired most of their tales from a middle-class circle of friends, who in turn were recounting tales learned from nurses, governesses, and servants, not all of them German. Thus the “German folktales” published by the Grimms included those from the oral folk traditions of other countries, and were also influenced by the literary fairy tales of writers like Straparola, Basile, D’Aulnoy, and Perrault in Italy and France.

Variants of Snow White were popular around the world long before the Grimms claimed it for Germany, but their version of the story (along with Walt Disney’s) is the one that most people know today. Elements from the story can be traced back to the oldest oral tales of antiquity, but the earliest known written version was published in Italy in 1634. This version was called The Young Slave, published in Giambattista Basile’s

Il Pentamerone

, and is believed to have influenced subsequent retellings—including a German text published by J. K. Musaus in 1784 and the Grimms’ text in 1812. In Basile’s story, a baron’s unmarried sister swallows a rose leaf and finds herself pregnant. She secretly gives birth to a beautiful baby girl, and names her Lisa. Fairies are summoned to bless the child, but the last one stumbles in her haste and utters an unfortunate curse instead. As a result, Lisa dies at the age of seven while her mother is combing her hair. The grieving mother has the body encased in seven caskets made of crystal, hidden in a distant room of the palace under lock and key. Some years later, lying on her deathbed, she hands the key to her brother, the baron, but makes him promise that he will never open the little locked door. More years pass, and the baron takes a wife. One day he is called to a hunting party, so he gives the key to his wife with strict instructions not to use it. Impelled by suspicion and jealousy, she heads immediately

for the locked room; there she discovers a beautiful young maiden who seems to be fast asleep. (Basile explains that Lisa has grown and matured in her enchanted state.) The baroness seizes Lisa by the hair—dislodging the comb and waking her. Thinking she’s found her husband’s secret mistress, the jealous baroness cuts off Lisa’s hair, dresses her in rags, and beats her black and blue. The baron returns and inquires after the ill-used young woman cowering in the shadows. His wife tells him that the girl is a kitchen slave, sent by her aunt. One day the baron sets off for a fair, having promised everyone in the household a gift, including even the cats and the slave. Lisa requests that he bring back a doll, a knife, and a pumice stone. After various troubles, he procures these things and gives them to the young slave. Alone by the hearth, Lisa talks to the doll as she sharpens the knife to kill herself—but the baron overhears her sad tale, and learns she’s his own sister’s child. The girl is then restored to beauty, health, wealth, and heritage—while the cruel baroness is cast away, sent back to her parents.

Il Pentamerone

, and is believed to have influenced subsequent retellings—including a German text published by J. K. Musaus in 1784 and the Grimms’ text in 1812. In Basile’s story, a baron’s unmarried sister swallows a rose leaf and finds herself pregnant. She secretly gives birth to a beautiful baby girl, and names her Lisa. Fairies are summoned to bless the child, but the last one stumbles in her haste and utters an unfortunate curse instead. As a result, Lisa dies at the age of seven while her mother is combing her hair. The grieving mother has the body encased in seven caskets made of crystal, hidden in a distant room of the palace under lock and key. Some years later, lying on her deathbed, she hands the key to her brother, the baron, but makes him promise that he will never open the little locked door. More years pass, and the baron takes a wife. One day he is called to a hunting party, so he gives the key to his wife with strict instructions not to use it. Impelled by suspicion and jealousy, she heads immediately

for the locked room; there she discovers a beautiful young maiden who seems to be fast asleep. (Basile explains that Lisa has grown and matured in her enchanted state.) The baroness seizes Lisa by the hair—dislodging the comb and waking her. Thinking she’s found her husband’s secret mistress, the jealous baroness cuts off Lisa’s hair, dresses her in rags, and beats her black and blue. The baron returns and inquires after the ill-used young woman cowering in the shadows. His wife tells him that the girl is a kitchen slave, sent by her aunt. One day the baron sets off for a fair, having promised everyone in the household a gift, including even the cats and the slave. Lisa requests that he bring back a doll, a knife, and a pumice stone. After various troubles, he procures these things and gives them to the young slave. Alone by the hearth, Lisa talks to the doll as she sharpens the knife to kill herself—but the baron overhears her sad tale, and learns she’s his own sister’s child. The girl is then restored to beauty, health, wealth, and heritage—while the cruel baroness is cast away, sent back to her parents.

The Young Slave contains motifs we recognize not only from Snow White but also Sleeping Beauty (the fairy’s curse), Bluebeard (the locked room), Beauty and the Beast (the troublesome gift), and other tales. An aunt-by-marriage plays the villain here—but a scheming stepmother is front and center in another peculiar Italian tale, titled “The Crystal Casket.” In this second Snow White variant, a lovely young girl is persuaded to introduce her teacher to her widowed father. Marriage ensues, but instead of gratitude, the teacher treats her stepdaughter cruelly. An eagle helps the girl to escape and hides her in a palace of fairies. The stepmother hires a witch, who takes a basket of poisoned sweetmeats to the girl. She eats one and dies. The fairies revive her. The witch strikes again, disguised as a tailoress with a beautiful dress to sell. When the dress is laced up, the girl falls down dead, and this time the fairies will not revive her. (They’re miffed that she keeps ignoring their warnings.) They place her body in a gem-encrusted casket, rope the casket to the back of a horse,

and send it off to the city. Horse and casket are found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful “doll” and takes her home. “But my son, she’s dead!” protests the queen. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, “consumed by love.” Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. His mother ignores the macabre creature—until a letter arrives warning her of the prince’s impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden’s dress. The queen thinks quickly. “Take off the dress! We’ll have another one made, and my son will never know.” As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his “wife.” (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) “My son,” says the Queen, “that girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her.” He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The girl is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

and send it off to the city. Horse and casket are found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful “doll” and takes her home. “But my son, she’s dead!” protests the queen. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, “consumed by love.” Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. His mother ignores the macabre creature—until a letter arrives warning her of the prince’s impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden’s dress. The queen thinks quickly. “Take off the dress! We’ll have another one made, and my son will never know.” As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his “wife.” (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) “My son,” says the Queen, “that girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her.” He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The girl is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

In a third Italian version of the tale, it’s the girl’s own mother who wishes her ill—an innkeeper named Bella Venezia who cannot stand a rival in beauty. First she imprisons her blossoming child in a lonely hut by the sea; then she seduces a kitchen boy and demands that he murder the girl. “Bring back her eyes and a bottle of her blood,” she says, “and I’ll marry you.” The servant abandons the girl in the woods, returning with the eyes and blood of a lamb. The girl wanders through the forest and soon finds a cave where twelve robbers live. She keeps house for the burly men, who love her and deck her in jewels every night—but her mother eventually gets wind of this, and is now more jealous than ever. Disguised as an old peddler woman, she sells her daughter a poisoned hair broach. When the robbers return, they find the girl dead, so they bury her in a hollow tree. At

length the fair corpse is discovered by a prince, who takes it home and fawns over it. The queen is appalled, but the prince insists upon marrying the beautiful maiden. Her body is bathed and dressed for a wedding. The royal hairdresser is summoned. As the girl’s hair is combed, the broach is discovered, removed, and she comes back to life.

length the fair corpse is discovered by a prince, who takes it home and fawns over it. The queen is appalled, but the prince insists upon marrying the beautiful maiden. Her body is bathed and dressed for a wedding. The royal hairdresser is summoned. As the girl’s hair is combed, the broach is discovered, removed, and she comes back to life.

In a Scottish version of the story, a trout in a well takes the role we now associate with a magical mirror. Each day a queen asks, “Am I not the loveliest woman in the world?” The trout assures the queen that she is … until her daughter comes of age, surpassing the mother in beauty. The queen falls ill with envy, summons the king, and demands the death of their daughter. He pretends to comply, but sends the girl off to marry a foreign king. Eventually the trout informs the queen that the princess is still alive—so she crosses the sea to her daughter’s kingdom, and kills her with a poisoned needle. The young king, grieving, locks his beloved’s corpse away in a high tower. Eventually he takes another wife, who notes that he always seems sad. “What gift,” she asks, “could I give to you, husband, so that you would know joy and laughter again?” He tells her that nothing can bring him joy but his first wife restored to life. She sends her husband up to the tower, where he finds his beloved alive and well—for his second wife had discovered the girl, and removed the poisoned needle from her finger. The lovers thus reunited, the good-hearted second wife offers to go away. “Oh! indeed you shall not go away,” says the king, “but I shall have both of you now.” They live happily together until (blast that trout!) the jealous queen gets wind of the fact that her daughter has come back to life. She crosses the ocean once again, bearing a poisoned drink this time. The clever second wife takes matters in hand. She greets the wicked queen on the shore, and tricks the woman into drinking from the poisoned cup herself. After this, the young king and his two wives enjoy a long, peaceful life. (I’ve always particularly liked this rendition, contrasting the toxic

mother-daughter relationship with the envy-free bond forged between the two wives.)

mother-daughter relationship with the envy-free bond forged between the two wives.)

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected their version of Snow White from Jeannette and Amalie Hassenpflug, family friends in the town of Cassel. (Ludwig Grimm, their brother, was engaged to marry a third Hassenpflug sister.) The Hassenpflug’s tale contains several elements from the earlier Italian stories, combined with imagery distinct to the lore of northern Europe. Dwarfs do not appear in the Italian variants, for instance, as dwarfs play little part in the Italian folk tradition. The Nordic and Germanic traditions, by contrast, contain a wealth of magical lore about burly little men who toil under the earth, associated with gems, iron ore, alchemy, and the blacksmith’s craft. The Grimms’ version starts, as so many fairy stories, with a barren queen who longs for a child. It’s a winter’s tale in this northern clime, set in a landscape of vast, icy forests. The queen stands sewing by an open window. She pricks her finger. Blood falls on the snow. “Would that I had a child,” she sighs, “as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame.” Her wish is granted, but the gentle queen expires as soon as her baby is born … or so most readers now believe. Yet the death of the queen, the “good mother,” was a plot twist introduced by the Grimms. In their earliest versions of the tale (the manuscript of 1810, and the first edition of 1812), it is Snow White’s natural mother whose jealousy takes a murderous bent. She was turned into an evil stepmother in editions from 1819 onward. “The Grimm Brothers worked on the

Kinder

-

und Hausmärchen

in draft after draft after the first edition of 1812,” Marina Warner explains (in her excellent fairy tale study,

From the Beast to the Blonde

), “Wilhelm in particular infusing the new editions with his Christian fervor, emboldening the moral strokes of the plot, meting out penalties to the wicked and rewards to the just to conform with prevailing Christian and social values. They also softened the harshness—especially in family dramas. They could not

make it disappear altogether, but in Hansel and Gretel, for instance, they added the father’s miserable reluctance to an earlier version in which both parents had proposed the abandonment of their children, and turned the mother into a wicked stepmother. On the whole, they tended towards sparing the father’s villainy, and substituting another wife for the natural mother, who had figured as the villain in versions they were told … . For them, the bad mother had to disappear in order for the ideal to survive and allow Mother to flourish as symbol of the eternal feminine, the motherland, and the family itself as the highest social desideratum.” It should also be noted that early Grimms’ fairy tales were not published with children in mind—they were published for scholars, in editions replete with footnotes and annotations. It was later, as the tales became popular with lay readers, families, and children, that the brothers took more care to delete material they deemed inappropriate, editing, revising, and sometimes rewriting the tales altogether.

Kinder

-

und Hausmärchen

in draft after draft after the first edition of 1812,” Marina Warner explains (in her excellent fairy tale study,

From the Beast to the Blonde

), “Wilhelm in particular infusing the new editions with his Christian fervor, emboldening the moral strokes of the plot, meting out penalties to the wicked and rewards to the just to conform with prevailing Christian and social values. They also softened the harshness—especially in family dramas. They could not

make it disappear altogether, but in Hansel and Gretel, for instance, they added the father’s miserable reluctance to an earlier version in which both parents had proposed the abandonment of their children, and turned the mother into a wicked stepmother. On the whole, they tended towards sparing the father’s villainy, and substituting another wife for the natural mother, who had figured as the villain in versions they were told … . For them, the bad mother had to disappear in order for the ideal to survive and allow Mother to flourish as symbol of the eternal feminine, the motherland, and the family itself as the highest social desideratum.” It should also be noted that early Grimms’ fairy tales were not published with children in mind—they were published for scholars, in editions replete with footnotes and annotations. It was later, as the tales became popular with lay readers, families, and children, that the brothers took more care to delete material they deemed inappropriate, editing, revising, and sometimes rewriting the tales altogether.

Other books

La biblia de los caidos by Fernando Trujillo

The Demetrios Bridal Bargain by Kim Lawrence

stargirl by Jerry Spinelli

Gabrielle: Bride of Vermont (American Mail-Order Bride 14) by Emily Claire

Manolito on the road by Elvira Lindo

Ghost Sniper: A Sniper Elite Novel by Scott McEwen, Thomas Koloniar

The Angst-Ridden Executive by Manuel Vazquez Montalban

Girl on the Best Seller List by Packer, Vin

Sanctuary by T.W. Piperbrook