Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective (21 page)

Read Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective Online

Authors: Geoffrey Beattie

Tags: #Behavioral Sciences

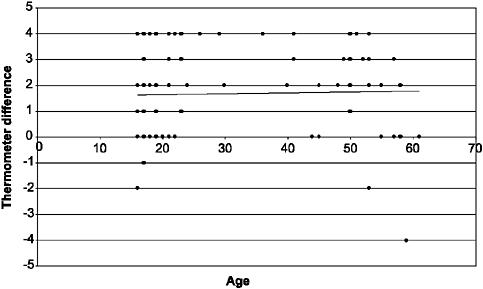

Figure 10.4

Age and thermometer difference correlations.

(the explicit measure) but not the other (the implicit measure). Of course, this latter finding is interesting because it suggests that as people get older they become more concerned about explicitly reporting their green credentials.

The fact that there was no significant correlation between the implicit and explicit measures also allows us to identify different sets of individuals with differing patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes.

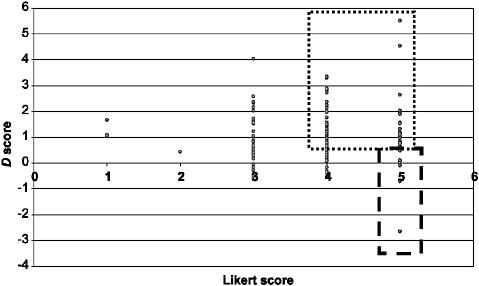

Figure 10.5

compares the Likert and

D

score results. While the majority of participants showed some degree of convergence between implicit and explicit attitudes with

D

scores > 0.8 and Likert scores of 4 and 5 (outlined by a dashed line in

Figure 10.5

), there were 13 participants in this first sample of 100 who, despite saying explicitly that they were very pro-low carbon with Likert scores of 5, had implicit attitudes that were not as positive, with

D

scores < 0.8 (outlined by a bold dashed line in

Figure 10.5

).

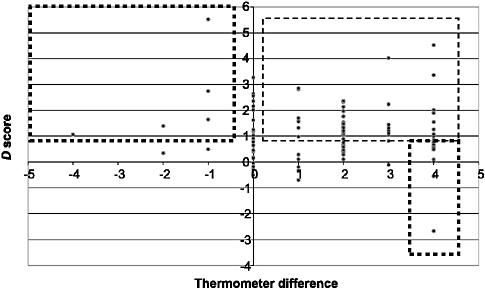

Figure 10.6

compares the thermometer difference and

D

score results. Again, the majority of participants displayed convergent attitudes, expressing a preference for low-carbon-footprint products at both the implicit and explicit levels (outlined by a dashed line on the right-hand side of

Figure 10.5

Likert and

D

score comparisons.

Figure 10.6

Thermometer difference and

D

score comparisons.

Figure 10.6

). However, there were two sets of participants that showed attitudinal divergence at both extremes. Overall, twelve participants (a similar number to those who displayed divergent attitudes using the Likert scale) explicitly stated that they were pro-low carbon with thermometer difference scores of 4, but their implicit attitudes were much less positive, with

D

scores < 0.8 (outlined by a bold dashed

line on the right-hand side of

Figure 10.6

). Interestingly, a second set consisting of five participants (outlined in bold to the left of

Figure 10.6

) expressed explicit attitudes that demonstrated a preference for high carbon (using the criterion of < 0 for thermometer difference scores); however, implicitly their attitudes appeared to be much more positive towards low carbon (with

D

scores > 0.8).

To recap, although the explicit measures of attitude (the feeling thermometer and Likert scale) were significantly correlated, the explicit and implicit measures were not correlated. This discrepancy seems to reflect some kind of ‘dissociation’, and has been reported previously in a number of other domains (see Banaji and Hardin 1996; Blair and Banaji 1996; Bosson, Swann and Pennebaker 2000; Devine 1989; Fazio, Jackson, Dunton and Williams 1995; Greenwald, McGhee and Schwartz 1998), although in other domains measures of implicit and explicit attitudes appear to be positively related (see Greenwald and Nosek 2001; Hofmann et al. 2005; Nosek and Banaji 2002; Nosek, Banaji and Greenwald 2002; Nosek and Smyth 2005).

Nosek (2007) has argued that ‘measurement innovations [such as the IAT] have spawned dual-process theories that, among other things, distinguish between the mind as we experience it (explicit), and the mind as it operates automatically, unintentionally, or unconsciously (implicit)’ (2007:184). So we have here the distinct possibility of two largely independent subsystems in the human mind, one that is familiar and one that is not. (Whether we have

any

‘conscious’ awareness at all of our implicit thinking, and whether the implicit process is always truly unconscious or whether we have some inkling of the underlying evaluation, remain to be properly investigated. The fact that something cannot be consciously controlled and manipulated does not of course mean that it resides purely and totally in the unconscious.) But how does this divergence between implicit and explicit attitude manifest itself within the individual, and does it have any effect on any aspects of observable behaviour? After all, a hundred years ago or so Freud showed how unconscious (and repressed) thoughts could find articulation through the medium of everyday speech in

the form of slips of the tongue. And how might this dissociation impact on people’s willingness or ability to actually do something about climate change? These are potentially important questions from both a theoretical and a practical point of view. It surprised me that nobody until now had attempted to answer them.

Speech and revealing movement

In order to make a first attempt at an answer here, we have to accept a major challenge and start thinking afresh about the very nature of everyday communication in which people express their underlying thoughts and ideas. After all, if we want to see the unconscious at work we must know where to look. When human beings talk, you will have noticed that they make many bodily movements, but in particular they make frequent (and largely unconscious) movements of the hands and arms. They do this in every possible situation – in face-to-face communication, on the telephone, even when the hands are below a desk and thus out of sight of their interlocutor (I have many recordings of these and similar occurrences). It is as if human beings are neurologically programmed to make these movements while they talk, and these visible movements would seem to be (in evolutionary terms) a good deal more primitive than speech itself, with language evolving on the back of them. These gestures are imagistic in form and closely integrated in time with the speech itself. They are called ‘iconic gestures’ because of their mode of representation. Words have an arbitrary relationship with the things they represent (and thus are ‘non-iconic’). Why do we call a particular object a ‘shoe’ or that large four-legged creature a ‘horse’? They could just as well be called something completely different (and, of course, they are called something completely different in other languages). But the unconscious gestural movements that we generate when we talk do not have this arbitrary relationship with the thing they are representing: their

imagistic form somehow captures certain aspects of the thing that they are representing (hence they are called ‘iconic’) and there is a good deal of cross-cultural similarity in their actual form (see Beattie 2003,

Chapter 6

).

Just visualise someone speaking, when they are fully engrossed in what they are saying, in order to understand the essential connections here between speech and hand movement. Below is a speaker who seems pretty engrossed in what he is saying. It is taken from a clip on the internet. It is Steve Ballmer, the CEO of Microsoft, and he is talking in an interview about future development of the PC and other ‘intelligent edge devices’:

|

|

Steve: The PC is an important part of the [overall ecosystem] that people are using... | Steve: I think there’s gonna be [two places of innovation] for development over the next few years. |

Iconic: Hands are close together, forming a sphere. | Iconic: Hands are closed into fists, a foot apart. |

Figure 11.1

Examples of the iconic gestures that accompany talk.

Just look at the elaborate hand movements, drawing out images in the space in front of his body. These imagistic gestures do not merely ‘illustrate’ the content of the speech; rather they are a core part of the underlying message. Steve Ballmer does not say what he intends to say and then try to make it clearer with a gestural illustration, after a brief pause. Rather he uses speech and movement simultaneously; the movements and the words both derive from the same underlying mental representation at exactly the same time (actually the beginning of the gestural movement slightly precedes the speech so that the hands can be in exactly the

Steve: I think that [people got very excited], appropriately, about the internet, html and browsers.

Iconic: Hands start off in front of the body and make a fast sweeping motion to the right of the body.

Figure 11.2

Further examples of the iconic gestures that accompany talk.