Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective (23 page)

Read Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective Online

Authors: Geoffrey Beattie

Tags: #Behavioral Sciences

Margaret Thatcher famously gave a ‘V for Victory’ sign to a group of journalists after her 1979 General Election win, but with the back of the hand facing the journalists, they were in a position to query the exact message that she was sending (and apparently some of them did query it, but not with the great woman herself!). It could, of course, have been her unconscious desires breaking through into overt behaviour. She might have been telling the journalists exactly what she thought of them.

But the spontaneous imagistic gestures that accompany everyday talk do not have standards of form like this. You cannot stop someone mid-flow and ask them why they used a particular imagistic movement. With these movements human beings create meaning spontaneously and unconsciously for other human beings without the benefit of a dictionary, and they seem to do this effortlessly and extremely frequently.

Stemming from the initial research of McNeill, the role of gesture in communication is now being extensively studied, opening up a new field within psychology. Such

research has consistently revealed that in order for the receiver to obtain the full meaning of an utterance, the two channels of communication need to be combined in order to form a more complete, overall representation of the message (Beattie and Shovelton 1999a, 1999b, 2001, 2002a, 2002b, 2006, 2009). So in one set of experiments we asked people to tell us what was going on in a set of cartoon stories and we filmed them telling these stories. We then played parts of their speech, with or without gestures, to another set of participants who were then quizzed about the original story (‘Was Billy sliding to the left?’). We found that where experimental participants were played either extracts of speech on their own or extracts of speech accompanied by the iconic gestures (played back on a video-screen), there was a clear advantage to seeing the gestures in addition to hearing the speech in terms of gaining information about the original stories (even though our participants often reported that they didn’t really

notice

the often small and insignificant gestures that occurred with the speech and weren’t aware of trying to decode them in any way). From these studies it became clear not only that significant information is encoded in the gestures that accompany speech, but also that receivers are able to decode this information successfully and quickly and combine this information with that encoded in the speech itself, and they are able to do this without any conscious awareness of where they got the information from.

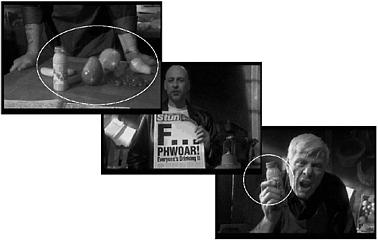

There are, of course, clear practical applications of this theoretical perspective. If significant semantic information is naturally split between the speech and the gestural channels, is it most effective to communicate information about (say) a commercial product using both channels, and how effective are these gestures at communicating aspects of the product compared to other types of images? With Heather Shovelton (Beattie and Shovelton 2005) I applied this theoretical perspective to television advertising (with the financial support of Carlton Television) to see whether gestures were more effective at communicating certain core properties of a product than the kinds of images that advertisers might traditionally use. We made some specific ads to promote an imaginary, but plausible, fruit drink

(indeed, so plausible was it that it subsequently came onto the market!). In the ad two characters talked to camera about a new fruit drink ‘F’ (‘with your five portions of fruit in one tiny little drink’). For one version of the ad, the speech– image advertisement, an advertising agency created its own images to convey three core properties of the product (

freshness

– juice sparkling on the fruit;

everyone is drinking it

– the

Stun

(

sic

) newspaper displaying the headline ‘Phwoar! Everyone’s drinking it’;

the size of the bottle

– the image of the actual bottle with respect to the hand), as shown in

Figure 11.7

.

For the other version of the ad, the speech–gesture advert, we included three iconic gestures that represented core aspects of the product, including: that the fruit was ‘fresh’ (hands together in front of chest, they move away from each other abruptly as fingers stretch and become wide apart), that ‘everyone’ was drinking it (right hand and arm move away from the body making a large sweeping movement) and the ‘size’ of bottle (hands move towards each other until they represent the size of the bottle), as shown in

Figure 11.8

. These gestures were selected on the basis of the fact that they were the kinds of unconscious movements that

Figure 11.7

Images representing ‘freshness’, ‘everyone’ and ‘size’.

Figure 11.8

Gestures representing ‘freshness’, ‘everyone’ and ‘size’.

people habitually make to represent these features when talking about these kinds of things. There tended to be a high degree of commonality in these representations across individuals (even without a dictionary of possible gestural representations to draw on).

We played these different versions of the ads to two independent groups of participants, and discovered that the use of speech and gesture together (including both the concrete ‘iconic’ gesture for ‘size’ and the more abstract ‘metaphoric’ gestures for ‘freshness’ and ‘everyone’) were more effective at communicating the core semantic features of the product than the speech and image version. So, it turns out that not only are these gestures highly informative, they are significantly more informative than other types of images that we might select (consciously and deliberately and with great creative thought) to represent core aspects of the product.

What is also interesting about the relationship between gestures and speech is that listeners interpret the gestures, and extract the critical information contained within them,

without any apparent conscious awareness. Ask them afterwards how they managed to pick up the critical details when they are only contained within the accompanying gestural movements, and generally speaking they don’t have a clue. They normally seem to assume that the speaker included that information in the speech itself, and only in the speech (‘there was someone waving his hand about, but I didn’t pay too much attention to that’ is a fairly common response).

However, there are times in everyday conversation where the speech and gesture channels do not gel in the normal way but rather the two channels may appear to contradict one another; this has become known as a ‘gesture–speech mismatch’ (Church and Goldin-Meadow 1986). Mismatches may occur for a variety of reasons. I have argued elsewhere that they occur when a speaker is trying to conceal critical information from a listener (see Beattie 2003). The basic idea here is that speakers control and edit their speech (because it is a conscious and reflective medium) when they are trying to tell a lie, but since they have less conscious control over their imagistic gesture, the spontaneous imagistic gesture emerges untarnished and reveals their underlying thought regardless. Hence, on occasion we find gestures and speech that do not match because the speech has been changed; the gesture has not.

Here are some examples of gesture–speech mismatches from various television programmes that I have worked on (Beattie,

Big Brother

2000–2009, Channel 4, UK; Beattie,

The Body Politic on News at Ten Thirty

, 2005, ITV, UK) with a possible explanation of why they occurred in the first place. The first example comes from one of the housemates, Adele, in the UK’s

Big Brother

Series 3. Here Adele is asked by the anonymous voice of ‘Big Brother’ who she thinks will be evicted by the public vote that evening. She uses a list structure (see Jefferson 1990) to give the order of who she thinks will go, starting with a contestant called Jade (soon to become very famous but who has since tragically died of cancer), then herself, then Jonny, then Kate. In other words, in her speech she is saying that she herself is very likely to be

evicted from the Big Brother house (she is saying, in effect, that she thinks she is in second position to Jade, and therefore has a high probability of going). But her gesture seems to be communicating something quite different here, as described in

Figure 11.9

.

One hand (the left hand) represents Jade, the right hand represents herself and the other two contestants (the square brackets indicate the start and end points of the meaningful part of the gesture, the so-called stroke phase). The gesture shows that she actually thinks that Jade is by far the most likely to be evicted from the house and that the other three (represented by a different hand, indicating considerable psychological distance between Jade going and the other three) are all safe. This interpretation is supported by the fact that when Adele was actually evicted that very evening, she was genuinely surprised by her eviction and the public vote. This is a gesture–speech mismatch because the speech seems to imply that she thought that she was likely to be evicted; the gesture does not show this.

The second example of a gesture–speech mismatch comes from the UK’s

Celebrity Big Brother

Series 2, and involves a well-known comedian called Les Dennis. Here, Les was the only housemate in a position to nominate for the forthcoming eviction (because he got zero on a Big Brother quiz) and he was explaining to Big Brother why the situation that he was in was so difficult for him. It’s important to remember that he knew that he wouldn’t have looked so good to the great British public if he had said it was going to be

Adele: [So Jade, then me, then Jonny, then Kate], I think that’s the order. |

Iconic: Hands and arms are wide apart and resting on the arms of a chair. Left hand rises slightly with index finger pointing forwards as she says ‘Jade’. Right hand then rises slightly as she says ‘then me’, index finger points forwards, finger moves slowly to the right and as it does so it makes three slight up-and-down movements. |

Figure 11.9

Adele’s gestures revealing what she is actually thinking.

easy to make the nominations (‘what a heartless man!’). This was his essential dilemma. So while Les was saying in his speech that the housemates were all really close (thus making it very difficult to nominate any of them), his gestures would suggest a very different interpretation. You would expect that if Les did, in fact, think the housemates were really close then his hands would have been much closer together during the generation of the gesture, reflecting this degree of closeness (because people do use positioning in the gestural space in front of the body in a consistent and meaningful way). However, in the critical gesture the hands were much further apart than one would expect, indicating that the housemates were not as close as Les was suggesting in his speech. Indeed the gesture was away from the other hand and away from the body. The hands were, in fact, signalling a significant psychological or emotional distance between the housemates, as described in

Figure 11.10

. Talking to Les, after the show was over, suggested that this interpretation was correct.

I have also identified mismatches in the talk of many politicians, including speeches of Tony Blair (then Prime Minister of the UK). In one particular speech (at the launch of the Labour manifesto in the run-up to the General Election in 2005), Blair was talking about possible rises in

Les: We [are all six of us, very, very, close] |

Metaphoric: Left hand is in front of left shoulder, palm is pointing forwards and fingers are straight and apart. Hand moves quickly to the left away from the body and then moves quickly back to its position in front of shoulder. This whole movement is repeated twice. The first half of the movement is then produced for a third time and the hand now remains away from the body. |

[really close] |

Metaphoric: Hands are wide apart, palms point towards each other. Hands move rapidly towards each other to an area in front of stomach but hands don’t touch – they stop when they are about six inches apart. |

Figure 11.10

Les’ gestures indicate a psychological distance between the housemates.