Why the West Rules--For Now (22 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Other fragments of evidence suggest this is perfectly possible. The most extraordinary is a set of mummies from the Tarim Basin, almost totally unknown to Westerners until the magazines

Discover, National Geographic, Archaeology

, and

Scientific American

gave them a publicity blitz in the mid-1990s. The mummies’ Caucasoid features seem to prove beyond doubt that people did move from central and even western Asia into China’s northwest fringes by 2000

BCE

. In a coincidence that

seems almost too good to be true, not only did the people buried in the Tarim Basin have beards and big noses like the Anban figurines; they were also partial to pointed hats (one grave contained ten woolen caps).

It is easy to get overexcited about a few unusual finds, but even setting aside the wilder theories, it looks like religious authority was as important in early China as in the early Hilly Flanks. And if any doubts remain, two striking discoveries from the 1980s should dispel them. Archaeologists excavating at Xishuipo were astonished to find a grave of around 3600

BCE

containing an adult man flanked by images of a dragon and a tiger laid out in clamshells. More clamshell designs surrounded the grave. One showed a dragon-headed tiger with a deer on its back and a spider on its head; another, a man riding a dragon. Chang suggested that the dead man was a shaman and that the inlays showed animal spirits that helped him to move between heaven and earth.

A discovery in Manchuria, far to the northeast, surprised archaeologists even more. Between 3500 and 3000

BCE

a cluster of religious sites covering two square miles developed at Niuheliang. At its heart was what the excavators called the “Goddess Temple,” an odd, sixty-foot-long semisubterranean corridor with chambers containing clay statues of humans, pig-dragon hybrids, and other animals. At least six statues represented naked women, life size or larger, sitting cross-legged; the best preserved had red painted lips and pale blue eyes inset in jade, a rare, hard-to-carve stone that was becoming the luxury good of choice all over China. Blue eyes being unusual in China, it is tempting to link these statues to the Caucasian-looking figurines from Anban and the Tarim Basin mummies.

Despite Niuheliang’s isolation, half a dozen clusters of graves are scattered through the hills around the temple. Mounds a hundred feet across mark some of the tombs, and the grave goods include jade ornaments, one of them carved into another pig-dragon. Archaeologists have argued, with all the ingenuity that lack of evidence brings out in us, over whether the men and women buried here were priests or chiefs. Quite possibly they were both at once. Whoever they were, though, the idea of burying a minority of the dead—usually men—with jade offerings caught on all over China, and by 4000

BCE

actual worship of the dead was beginning at some cemeteries. It looks as if people in the

Eastern core were just as concerned about ancestors as those in the Hilly Flanks, but expressed their concern in different ways—by removing skulls from the dead and keeping them among the living in the West, and by honoring the dead at cemeteries in the East. But at both ends of Eurasia the greatest investments of energy were in ceremonies related to gods and ancestors, and the first really powerful individuals seem to have been those who communicated with invisible worlds of ancestors and spirits.

By 3500

BCE

agricultural lifestyles rather like those created in the West several millennia earlier—involving hard work, food storage, fortifications, ancestral rites, and the subordination of women and the young to men and the old—seem to have been firmly established in the Eastern core and were expanding from there. The Eastern agricultural dispersal also seems to have worked rather like that in the West; or, at least, the arguments among the experts take similar forms in both parts of the world. Some archaeologists think people from the core area between the Yellow and Yangzi rivers migrated across East Asia, carrying agriculture with them; others, that local foraging groups settled down, domesticated plants and animals, traded with one another, and developed increasingly similar cultures over large areas. The linguistic evidence is just as controversial as in Europe, and as yet there are not enough genetic data to settle anything. All we can say with confidence is that Manchurian foragers were living in large villages and growing millet by at least 5000

BCE

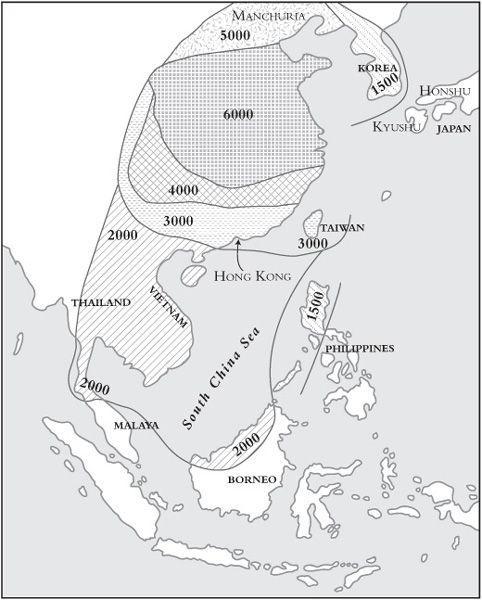

. Rice was being cultivated far up the Yangzi Valley by 4000, on Taiwan and around Hong Kong by 3000, and in Thailand and Vietnam by 2000. By then it was also spreading down the Malay Peninsula and across the South China Sea to the Philippines and Borneo (

Figure 2.8

).

Just like the Western agricultural expansion, the Eastern version also hit some bumps. Phytoliths show that rice was known in Korea by 4400

BCE

and millet by 3600, the latter reaching Japan by 2600, but prehistoric Koreans and Japanese largely ignored these novelties for the next two thousand years. Like northern Europe, coastal Korea and Japan had rich marine resources that supported large, permanent villages ringed by huge mounds of discarded seashells. These affluent foragers developed sophisticated cultures and apparently felt no urge to take up farming. Again like Baltic hunter-gatherers in the thousand years between

5200 and 4200

BCE

, they were numerous (and determined) enough to see off colonists who tried to take their land but not so numerous that hunger forced them to take up farming to feed themselves.

Figure 2.8. Going forth and multiplying, version two: the expansion of agriculture from the Yellow-Yangzi valleys, 6000–1500

BCE

In both Korea and Japan the switch to agriculture is associated with the appearance of metal weapons—bronze in Korea around 1500

BCE

and iron in Japan around 600

BCE

. Like European archaeologists who argue over whether push or pull factors ended the affluent Baltic foraging societies, some Asianists think the weapons belonged to invaders who brought agriculture in their train while others suggest that internal changes so transformed foraging societies that farming and metal weapons suddenly became attractive.

By 500

BCE

rice paddies were common on Kyushu, Japan’s southern island, but the expansion of farming hit another bump on the main island of Honshu. It took a further twelve hundred years to get a foothold on Hokkaido in the north, where food-gathering opportunities were particularly rich. But in the end, agriculture displaced foraging as completely in the East as in the West.

BOILING AND BAKING, SKULLS AND GRAVES

How are we to make sense of all this? Certainly East and West were different, from the food people ate to the gods they worshipped. No one would mistake Jiahu for Jericho. But were the cultural contrasts so strong that they explain why the West rules? Or were these cultural traditions just different ways of doing the same things?

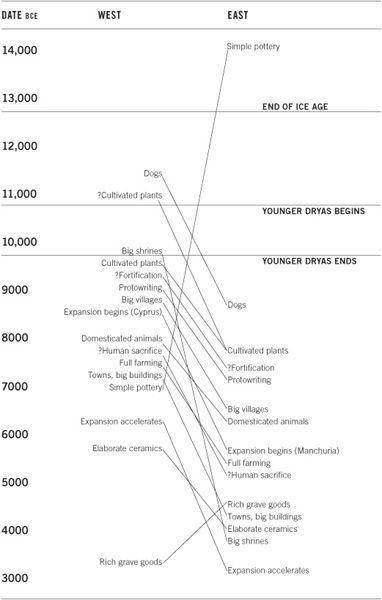

Table 2.1

summarizes the evidence. Three points, I think, jump out. First, if the culture created in the Hilly Flanks ten thousand years ago and from which subsequent Western societies descend really did have greater potential for social development than the culture created in the East, we might expect to see some strong differences between the two sides of

Table 2.1

. But we do not. In fact, roughly the same things happened in both East and West. Both regions saw the domestication of dogs, the cultivation of plants, and domestication of large (by which I mean weighing over a hundred pounds) animals. Both saw the gradual development of “full” farming (by which I mean high-yield, labor-intensive systems with fully domesticated plants and wealth and gender hierarchy), the rise of big villages (by which I mean more than a hundred people), and, after another two to three thousand years, towns (by which I mean more than a thousand people). In both regions people constructed elaborate buildings and fortifications, experimented with protowriting, painted beautiful designs on pots, used lavish tombs, were fascinated with ancestors, sacrificed humans, and gradually expanded agricultural lifestyles (slowly at first, accelerating after about two thousand years, and eventually swamping even the most affluent foragers).

Table 2.1. The beginnings of East and West compared

Second, not only did similar things happen in both East and West, but they also happened in more or less the same order. I have illustrated this in

Table 2.1

with lines linking the parallel developments in each region. Most of the lines have roughly the same slope, with developments coming first in the West, followed about two thousand years later by the East.

*

This strongly suggests that developments in the East and West shared a cultural logic; the same causes had the same consequences at both ends of Eurasia. The only real difference is that the process started two thousand years earlier in the West.

Third, though, neither of my first two points is

completely

true. There are exceptions to the rules. Crude pottery appeared in the East at least seven thousand years earlier than in the West, and lavish tombs one thousand years earlier. Going the other way, Westerners built monumental shrines more than six thousand years before Easterners. Anyone who believes that these differences set East and West off along distinct cultural trajectories that explain why the West rules needs to show why pottery, tombs, and shrines matter so much, while anyone (me, for instance) who believes they did not really matter needs to explain why they diverge from the general pattern.

Archaeologists mostly agree why pottery appeared so early in the East: because the foods available there made boiling so important. Easterners needed containers they could put on a fire and consequently mastered pottery very early. If this is right, rather than focusing on the pottery itself, we should perhaps be asking whether differences in food preparation locked East and West into different trajectories of development. Maybe, for instance, Western cooking provided more nutrients, making for stronger people. That, though, is not very convincing. Skeletal studies give a rather depressing picture of life in both the Eastern and Western agricultural cores: it was, as the seventeenth-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes more or less put it, poor, nasty, and short (though not necessarily brutish). In East and West alike early farmers were malnourished and stunted, carried heavy parasite loads, had bad teeth, and died young; in both regions, improvements

in agriculture gradually improved diet; and in both regions, fancier elite cuisines eventually emerged. The Eastern reliance on boiling was one among many differences in cooking, but overall, the similarities between Eastern and Western nutrition vastly outweigh the differences.

Or maybe different ways of preparing food led to different patterns of eating and different family structures, with long-term consequences. Again, though, it is far from obvious that this actually happened. In both East and West the earliest farmers seem to have stored, prepared, and perhaps eaten food communally, only to shift across the next few millennia toward doing these things at the family level. Once more, East-West similarities outweigh differences. The early Eastern invention of pottery is certainly an interesting difference, but it does not seem very relevant to explaining why the West rules.

What of the early prominence of elaborate tombs in the East and the even earlier prominence of elaborate shrines in the West? These developments, I suspect, were actually mirror images of each other. Both, as we have seen, were intimately linked to an emerging obsession with ancestors at a time when agriculture was making inheritance from the dead the most important fact of economic life. For reasons we will probably never understand, Westerners and Easterners came up with different ways to give thanks to and get in contact with the ancestors. Some Westerners apparently thought that passing their relatives’ skulls around, filling buildings with bulls’ heads and pillars, and sacrificing people in them would do the trick; Easterners generally felt better about burying carved jade animals with their relatives, worshipping their tombs, and eventually beheading other people and throwing them in the grave too. Different strokes for different folks; but similar results.