Why the West Rules--For Now (9 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

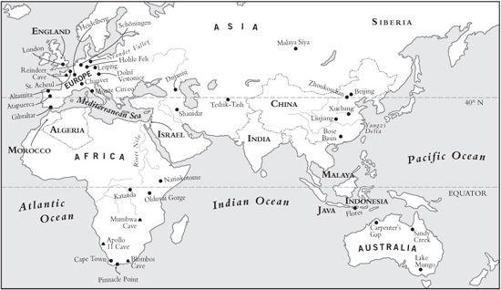

Figure 1.1. Before “East” and “West” meant much: locations in the Old World mentioned in this chapter

For 25,000 generations Handy Men scampered and swung through the trees in this little corner of the world, chipping stone tools, grooming each other, and mating. Then, somewhere around 1.8 million years ago, they disappeared. So far as we can tell this happened rather suddenly, although one of the problems in studying human evolution is the difficulty of dating finds precisely. Much of the time we depend on the fact that the layers of rock containing the fossil bones or tools may also contain unstable radioactive isotopes whose rate of decay is known, so that measuring the ratios between the isotopes gives dates for the finds. These dates, however, can have margins of error tens of thousands of years wide, so when we say the world of

Homo habilis

ended suddenly, “suddenly” may mean a few lifetimes or a few thousand lifetimes.

When Charles Darwin was thinking about natural selection in the 1840s and 1850s he assumed that it worked through the slow accretion of tiny changes, but in the 1970s the biologist Stephen Jay Gould suggested instead that for long periods nothing much happens, then some event triggers a cascade of changes. Evolutionists nowadays divide over whether gradual change (evolution by creeps, as its critics call it) or Gould’s “

punctuated equilibrium

” (evolution by jerks) is better as a general model, but the latter certainly seems to make most sense of

Homo habilis

’s disappearance. About 1.8 million years ago East Africa’s climate was getting drier and open savannas were replacing the forests where

Homo habilis

lived; and at just that point, new kinds of ape-men

*

took Handy Man’s place.

I want to hold off putting a name on these new ape-men, and for now will just point out that they had bigger brains than

Homo habilis

, typically about 800 cc. They lacked the long, chimplike arms of

Homo habilis

, probably meaning that they spent nearly all their time on the ground. They were also taller. A million-and-a-half-year-old skeleton from Nariokotome in Kenya, known as the Turkana Boy, belongs to a five-foot-tall child who would have reached six feet had he survived to adulthood. As well as being longer, his bones were less robust than those of

Homo habilis

, suggesting that he and his contemporaries relied more on their wits and tools than on brute strength.

Most of us think that being smart is self-evidently good. Why, then, if

Homo habilis

had the potential to mutate in this direction, did they putter along for half a million years before “suddenly” morphing into taller, bigger-brained creatures? The most likely explanation lies in the fact that there is no such thing as a free lunch. A big brain is expensive to run. Our own brains typically make up 2 percent of our body weight but use up 20 percent of the energy we consume. Big brains create other problems too: it takes a big skull to hold a big brain—so big, in fact, that modern women have trouble pushing babies with such big heads down their birth canals. Women deal with this by in effect giving birth prematurely. If our babies stayed in the womb until they were almost self-sufficient (like other mammals), their heads would be too big for them to get out.

Yet risky childbirth, years of nurturing, and huge brains that burn up one fifth of our food intake are all fine with us—finer, anyway, than using the same amounts of energy to grow claws, more muscles, or big teeth. Intelligence is much more of a plus than any of these alternatives. It is less obvious, though, why a genetic mutation producing bigger brains gave ape-men enough advantages to make the extra energy costs worthwhile a couple of million years ago. If being smarter had not been beneficial enough to pay the costs of supporting these gray cells, brainy apes would have been less successful than their dumber relatives, and their smart genes would have quickly disappeared from the population.

Perhaps we should blame it on the weather. When the rains failed and the trees the ape-men lived in started dying, brainier and perhaps more sociable mutants might well have gained an edge over their more apelike relatives. Instead of retreating ahead of the grasslands, the clever apes found ways to survive on them, and in the twinkling of an eye (on the timescale of evolution) a handful of mutants spread their genes through the whole pool and completely replaced the slower-witted, undersized, forest-loving

Homo habilis

.

THE BEGINNINGS OF EAST AND WEST?

Whether because their home ranges got crowded, because bands squabbled, or just because they were curious, the new ape-men were

the first such creatures to leave East Africa. Their bones have been found everywhere from the southern tip of the continent to the Pacific shores of Asia. We should not imagine great waves of migrants like something out of a cowboy movie, though; the ape-men were surely barely conscious of what they were doing, and crossing these vast distances required even vaster stretches of time. From Olduvai Gorge to Cape Town in South Africa is a long way—two thousand miles—but to cover this ground in a hundred thousand years (the length of time it apparently took) ape-men only needed, on average, to expand their foraging range by 35 yards each year. Drifting northward at the same rate would take them to the threshold of Asia, and in 2002 excavators at Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia found a 1.7-million-year-old skull that combines features of

Homo habilis

and the newer ape-men. Stone tools from China and fossil bones from Java (then still joined to the Asian mainland) may be almost as old, implying that after leaving Africa the ape-men picked up speed, averaging a cracking pace of 140 yards per year.

*

We can only realistically expect to distinguish Eastern and Western ways of life after ape-men left East Africa, spreading through the warm, subtropical latitudes as far as China; and an East-West distinction may be just what we do find. By 1.6 million years ago, there are obvious Eastern and Western patterns in the archaeological record. The question, though, is whether these contrasts are important enough that we should imagine distinct ways of life lying behind them.

Archaeologists have known about these East-West differences since the 1940s, when the Harvard archaeologist Hallam Movius noticed that the bones of the new, brainy ape-men were often found in association with new kinds of flaked stone tools. Archaeologists called the most distinctive of these tools “Acheulean hand axes” (“ax” because they look like axheads, even though they were clearly used for cutting, poking, and pounding as well as chopping; “hand” because they were handheld, rather than being attached to sticks; and Acheulean after the small French town of St. Acheul, where they were first found in large numbers). Calling these tools works of art might be excessive, but their simple symmetry is often much more beautiful than Handy Men’s

cruder flakes and chopping tools. Movius noticed that while Acheulean hand axes were common in Africa, Europe, and southwest Asia, none had been found in East or Southeast Asia. Instead, Eastern sites produced rougher tools much like the pre-Acheulean finds associated with

Homo habilis

in Africa.

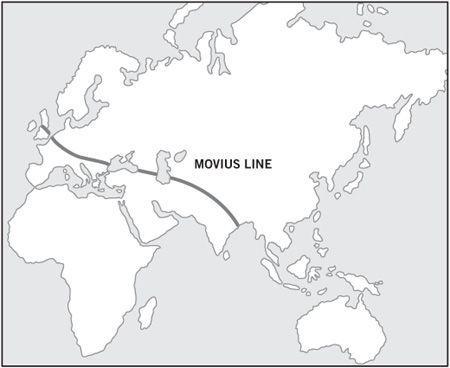

If the so-called Movius Line (

Figure 1.2

) really does mark the beginning of separate Eastern and Western ways of life, it could also provide an astonishingly long-term lock-in theory—one holding that almost as soon as ape-men moved out of Africa, they divided between Western/technologically advanced/Acheulean hand ax cultures in Africa and southwest Asia and Eastern/technologically less advanced/flake-and-chopper cultures in East Asia. No wonder the West rules today, we might conclude: it has led the world technologically for a million and a half years.

Figure 1.2. The beginnings of East and West? This map shows the Movius Line, which for about a million years separated Western hand-ax-using cultures from Eastern flake-and-chopper-using cultures.

Identifying the Movius Line, though, is easier than explaining it. The earliest Acheulean hand axes, found in Africa, are about 1.6 million years old, but there were already ape-men at Dmanisi in Georgia a hundred thousand years before that. The first ape-men clearly left Africa before the Acheulean hand ax became a normal part of their toolkit, carrying pre-Acheulean technologies across Asia while the Western/African region went on to develop Acheulean tools.

A quick glance at

Figure 1.2

, though, shows that the Movius Line does not divide Africa from Asia; it actually runs through northern India. This is an important detail. The first migrants left Africa

before

Acheulean hand axes were invented, so there must have been subsequent waves of migration out of Africa, bringing hand axes to southwest Asia and India. So we need to ask a new question: Why did these later waves of ape-men not take Acheulean technology even farther east?

The most likely answer is that rather than marking the boundary between a technologically advanced West and a less-advanced East, the Movius Line merely separates Western regions where access to the sort of stones needed for hand axes is easy from Eastern areas where such stones are rare and where good alternatives—such as bamboo, which is tough but does not survive for us to excavate—are easily available. According to this interpretation, as hand-ax users drifted across the Movius Line they gradually gave Acheulean tools up because they could not replace broken ones. They carried on producing choppers and flakes, for which any old pebble would do, but perhaps started using bamboo for tasks previously done with stone hand axes.

Some archaeologists think finds from the Bose Basin in south China support this thinking. About 800,000 years ago a huge meteor crashed here. It was a disaster on an epic scale, and intense fires burned millions of acres of forest. Before the impact, ape-men in the Bose Basin had used choppers, flakes, and (presumably) bamboo, like other East Asians; but when they returned after the fires they started making hand axes rather like the Acheulean ones—perhaps, the theory runs, because the fires had burned off all the bamboo, in the process exposing usable cobbles. After a few centuries, as the vegetation grew back, the locals gave up hand axes and went back to bamboo.

If this speculation is right, East Asian ape-men were perfectly capable of making hand axes when conditions favored these tools, but

normally did not bother because alternatives were more easily available. Stone hand axes and bamboo tools were just two different tools for doing the same jobs, and ape-men all lived in much the same ways, whether they found themselves in Morocco or Malaya.

That makes reasonable sense, but, this being prehistoric archaeology, there are other ways of looking at the Movius Line too. So far I have avoided giving a name to the ape-men who used Acheulean hand axes, but at this point the name we give them starts to matter.

Since the 1960s most paleoanthropologists have called the new species that evolved in Africa about 1.8 million years ago

Homo erectus

(“Upright Man”) and have assumed that these creatures wandered through the subtropical latitudes to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. In the 1980s, however, some experts began focusing on subtle differences between

Homo erectus

skulls found in Africa and those found in East Asia. They suspected that they were in fact looking at two different species of ape-men. They coined a new name,

Homo ergaster

(“Working Man”), for those who evolved in Africa 1.8 million years ago and then spread all the way to China. Only when

Homo ergaster

reached East Asia, they suggested, did

Homo erectus

evolve from them.

Homo erectus

was therefore a purely East Asian species, distinct from the

Homo ergaster

who filled Africa, southwest Asia, and India.

If this theory is correct, the Movius Line was not just a trivial difference in tool types: it was a genetic watershed that split early ape-men in two. In fact, it raises the possibility of what we might call the mother of all long-term lock-in theories: that East and West are different because Easterners and Westerners are—and have been for more than a million years—different kinds of human beings.