Why the West Rules--For Now (84 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

When we look at reactions to Western rule within a longer time frame, we in fact see two striking correlations. The first is that those regions that had relatively high social development before Western rule, like the Eastern core, tended to industrialize themselves faster than those that had relatively low development scores; the second, that those regions that avoided direct European colonization tended to industrialize faster than those that did become colonies. Japan had high social development before 1853 and was not colonized; its modernization took off in the 1870s. China had high development and was partly colonized; its modernization took off in the 1950s. India had moderate development and was fully colonized; its modernization did not take off until the 1990s. Sub-Saharan Africa had low development and full colonization, and is only now starting to catch up.

Because the nineteenth-century East was (by preindustrial standards) a world of advanced agriculture, great cities, widespread literacy, and powerful armies, plenty of its residents found ways to adapt Western methods to a new setting. Easterners even adopted Western debates about industrialism. For every Eastern capitalist there was an aging samurai to grumble, “

Useless beauty

had a place in the old life, but the new asks only for ugly usefulness,” and although real wages were creeping up in the cities by 1900, Chinese and Japanese dissenters eagerly formed socialist parties. By 1920 their members included the young Mao Zedong.

Eastern debates over industrialization varied from country to country. Just as happened in the West, there was little or nothing that great men, bungling idiots, culture, or dumb luck could have done to prevent an industrial takeoff once the possibility arose, but—again paralleling the West—these forces had everything to do with deciding which country led the way.

When W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan presented their comic opera

The Mikado

in London in 1885, they took Japan as the very model

of the exotic orient, just the sort of place where little birds died for love and lord high executioners had to cut their own heads off. In reality, though, Japan was already industrializing faster than any previous society in history. Adroitly stage-managing the young new emperor installed in 1868 after the civil war, clever operators in Tokyo managed to keep their country out of wars with Western powers, finance industrialization largely from native capital, and dissuade the angry people from provocative attacks on foreigners. Clumsy operators in Beijing, by contrast, tolerated and even encouraged violence against missionaries, blundered into war with France in 1884 (losing most of their expensive new fleet in an hour), and borrowed—and embezzled—on a ruinous scale.

Japan’s elite faced up to the fact that liberalization was a package deal. They put on top hats or crinolines; some discussed adopting the Latin script; others wanted Japan to speak English. They were ready to consider anything that might work. China’s Qing rulers, however, were division personified. For forty-six years the dowager empress Cixi ruled from behind the bamboo curtain, opposing any modernization that might endanger the dynasty. Her one flirtation with Western ideas was to divert money intended for rebuilding the fleet into a marble copy of a Mississippi paddleboat for her summer palace (still there and well worth seeing). When her nephew Guangxu tried to rush through a hundred-day reform program in 1898 (streamlining the civil service, updating the examinations, creating modern schools and colleges, coordinating tea and silk production for export, promoting mining and railroads, and Westernizing the army and navy), Cixi announced that Guangxu had asked her to come back as regent, then locked him in the palace and executed his modernizing ministers. Guangxu remained a reformer to his bitter end, poisoned by arsenic as Cixi lay on her own deathbed in 1908.

While China stumbled toward modernity, Japan raced. In 1889 Japan published a constitution giving wealthy men the vote, allowing Western-style political parties, and creating modern government ministries. China approved a constitution only in Cixi’s dying days, allowing limited male voting in 1909, but Japan made mass education a priority. By 1890 two-thirds of Japanese boys and one-third of girls received free primary schooling, while China did virtually nothing to educate the masses. Both countries laid their first railroads in 1876, but

Shanghai’s governor tore out China’s tracks in 1877, fearing that rebels might use them. In 1896 Japan had 2,300 miles of railway; China, just 370. Much the same story could be told about iron, coal, steam, or telegraph lines.

Throughout history, the expansion of cores has often set off ferocious wars on the peripheries to decide which part of the fringe would lead resistance (or assimilation) to the great powers. In the first millennium

BCE

, for instance, Athens, Sparta, and Macedon warred for a century and a half on the fringes of the Persian Empire; and Chu, Wu, and Yue did the same in southern China as the core in the Yellow River valley grew. In the nineteenth century

CE

, the process repeated itself when the East became a periphery to the West.

Ever since Japan’s abortive effort to conquer China in the 1590s, rulers in the Eastern core had assumed that the costs of interstate war would outweigh the benefits, but the coming of the West turned that assumption on its head. Whichever Eastern nation industrialized, reorganized, and rearmed fastest would be able not just to hold the Western imperialists off but also to hold the rest of the East down.

It was ultimately Japanese industrialization, not British warships, that was China’s nemesis. Japan lacked resources; China had plenty. Japan needed markets; China was full of them. Arguments in Tokyo over what should be done were furious and even murderous, but across two generations the country gradually committed to forcing its way into China’s materials and markets. By the 1930s Japan’s most militant officers had determined to take over the entire Eastern core, turn China and Southeast Asia into colonies, and expel the Western imperialists. A War of the East had begun.

The great difference between this War of the East and the eighteenth-century War of the West, though, was that the War of the East took place in a world where the West already ruled. This complicated everything. Thus in 1895 when Japan swept aside Chinese resistance to its advances in Korea, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II reacted by sending his cousin Tsar Nicholas II of Russia a rather awful drawing called “The Yellow Peril” (

Figure 10.7

), urging him “

to cultivate

the Asian Continent and to defend Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race.” Nicholas responded by confiscating much of the territory Japan had seized from China.

Figure 10.7. “The Yellow Peril,” an 1895 drawing based on a sketch by Kaiser Wilhelm II, aimed, he explained, to encourage Europeans “

to unite

in resisting the inroad of Buddhism, heathenism, and barbarism for the Defense of the Cross.”

Other Westerners, though, saw advantages in working with Japan, using its burgeoning power to police the East for them. The first opportunity came in 1900, when a Chinese secret society called the Boxers United in Righteousness rose up against Western imperialism (claiming, among other things, that a hundred days of martial-arts training would make its members bulletproof). It took twenty thousand foreign troops to suppress them; and most of the soldiers—though you would not know it from Western accounts (particularly the 1963 Hollywood blockbuster

55 Days in Peking

)—were Japanese. So pleased was Britain with this outcome that in 1902 it signed a naval alliance recognizing Japan’s great-power status in the East. Confident of British neutrality, in 1904 Japan took its revenge on Russia, sinking its Far Eastern fleet and overwhelming its army in the biggest land battle ever fought. When Tsar Nicholas sent his main fleet twenty thousand miles around the Old World to put matters right, Japanese battleships sank it, too.

Fewer than fifty years had passed since Looty relocated to London, but the old Eastern core had responded so dynamically that it could already defeat a Western empire. “

What happened

… in 1904–5,” the disgraced Russian commander Aleksei Nikolaevich Kuropatkin concluded, “was nothing more than a skirmish with the advance guard … Only with a common recognition that keeping Asia peaceful is a matter of importance to all of Europe … can we keep the ‘yellow peril’ at bay.” But Europe ignored his advice.

THE WARS OF THE WORLD

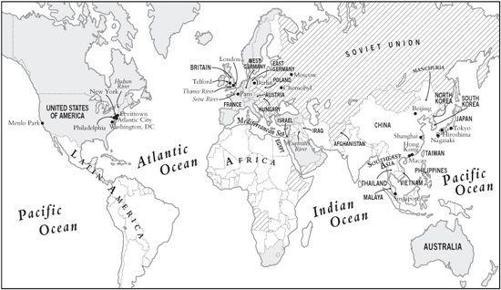

Between 1914 and 1991 the Western core fought the greatest wars in history: the First World War, between 1914 and 1918, to determine whether Germany would create a European land empire; the Second, between 1939 and 1945, over the same question; and the Cold War, between 1947 and 1991, to settle how the United States and Soviet Union would divide the spoils (

Figure 10.8

). Together these added up to a new War of the West that dwarfed the eighteenth-century version. It subsumed the War of the East, left a hundred million dead, and threatened humanity’s very survival. In 1991 the West still ruled, but it seemed to many that Kuropatkin’s fears were finally coming true: the East was poised to overtake it.

The story of how the new War of the West began has often been told—how the Ottoman Empire’s long decline filled the Balkans with terrorists/freedom fighters; how, through bungling and bad luck, a gang called the Black Hand murdered the heir to Austria’s Habsburg throne in June 1914 (the bomb tossed by the would-be assassin bounced off the Austrian archduke’s car, only for the chauffeur to take a wrong turn, back up, and stop right in front of a second assassin, who made no mistake); and how the web of treaties designed to keep Europe’s peace dragged everyone over the precipice together.

What followed is equally well known—how Europe’s modernized states called up their young men in unprecedented numbers, armed them with unprecedented weapons, and bent their vast energies to unprecedented slaughter. Before 1914, some intellectuals had argued that great-power war had become impossible because the world’s economies were now so interlinked that the moment war broke out all of them would collapse, ending the conflict. By 1918, though, the lesson seemed to be that only those states that could effectively harness their vast, complex economies could survive the strains of twentieth-century total war.

Figure 10.8. The world at war, 1914–1991. Gray shading shows the United States and its major allies around 1980; the Soviet Union and its major allies are indicated by diagonal lines.

The war seemed to have shown that the advantage lay with liberal, democratic states, whose citizens were most fully committed to the struggle. Back in the first millennium

BCE

, Easterners and Westerners had all learned that dynastic empires were the most effective organizations for waging war; now, in the space of a single decade, they learned that these dynastic empires—history’s most enduring form of government, with an unbroken heritage from Assyria, Persia, and Qin—were no longer compatible with war.

First to go was China’s Qing dynasty. Mired in debt, defeat, and disorder, the boy emperor Puyi’s ministers lost control of the army as early as 1911, but when the rebel general Yuan Shikai promoted himself to emperor in 1916—as rebel generals had been doing for two thousand years—he found that he could not hold the country together either. Another military clique restored Puyi in 1917, with no better results. China’s imperial history ended a few days later, if not with a whimper then with just a very small bang: a single airplane dropped a bomb on the Forbidden City in Beijing, Puyi was deposed again, and the country descended into anarchy.

Next was Russia’s Romanov dynasty. Defeat by Japan had almost toppled Tsar Nicholas in 1905, but the First World War finished the job. In 1917 liberals swept his family from power and in 1918 Bolsheviks shot them. Germany’s Hohenzollerns and Austria’s Habsburgs quickly followed, escaping the Romanovs’ fate only by fleeing their homelands. In Turkey the Ottomans limped on, but only until 1922.