Why the West Rules--For Now (83 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

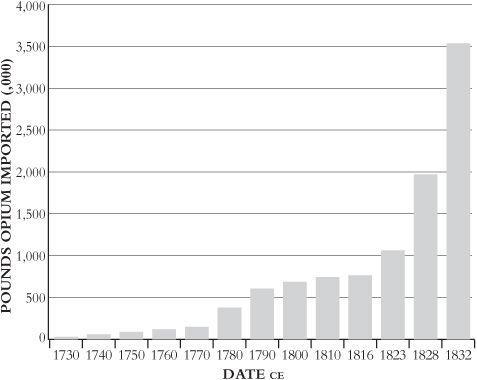

Figure 10.5. Just say yes: the British East India Company’s soaring opium sales in Guangzhou, 1730–1832

The dealers insisted that opium “

simply did

for the upper levels of Chinese society what brandy and champagne did for the same levels in England,” but that was not true, and they knew it. Opium left a trail of broken lives as grim as anything in today’s inner cities. It also hurt peasants who had never even seen an opium pipe, because the outflow of silver to the drug lords increased the value of the metal, forcing farmers to sell more crops to raise the silver they needed to pay their taxes. By 1832 taxes were effectively twice as high as they had been fifty years before.

Some of Emperor Daoguang’s advisers recommended a cynical market solution: legalize opium so that homegrown poppies would undercut British imports, stanching the outflow of silver and increasing tax revenues. But Daoguang was a good Confucian, and instead of caving in to his subjects’ baser urges, he wanted to save them from themselves. In 1839 he declared war on drugs.

I said a few words about this first war on drugs in the introduction. At first it went well. Daoguang’s drug czar confiscated tons of opium,

burned it, and dumped it in the ocean (after writing a suitably classical poem of apology to the sea god for polluting his realm). But then it went less well. The British trade commissioner, recognizing that where the magic of the market would not work that of the gun might do better, dragged his unwilling homeland into a shooting war with China.

What followed was a shocking demonstration of the power of industrial-age warfare. Britain’s secret weapon was the

Nemesis

, a brand-new all-iron steamer. Even the Royal Navy had reservations about such a radical weapon; as her captain admitted, just “

as the

floating

property of wood, without reference to its shape or fashion, rendered it the most natural material for the construction of ships, so did the

sinking

property of iron make it appear, at first sight, very ill adapted for a similar purpose.”

These worries seemed well-founded. The iron hull made the compass malfunction; the

Nemesis

hit a rock even before leaving England; and she almost cracked in two off the Cape of Good Hope. Only by hanging overboard in a howling gale and bolting odd bits of lumber and iron to her sides did her captain keep her afloat. But on reaching Guangzhou all was forgiven. The

Nemesis

lived up to her name, steaming up shallow passages where no wooden ship could go and blasting all opposition to pieces.

In 1842 the British ships closed the Grand Canal, bringing Beijing to the verge of famine. Governor-General Qiying, charged with negotiating peace, assured his emperor that he could still “

pass over these

small matters and achieve our larger scheme,” but in reality he handed the British—then the Americans, then the French, then other Westerners—the access to Chinese ports that they demanded. And when Chinese hostility toward these foreign devils (

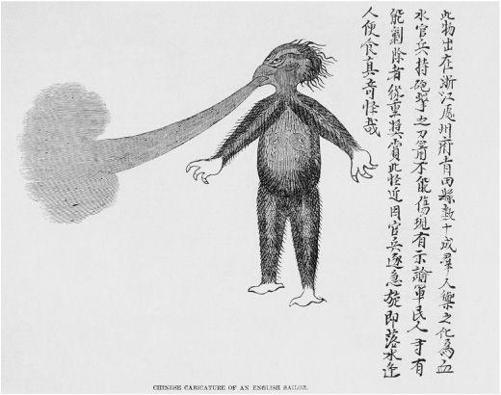

Figure 10.6

) made the concessions less profitable than expected, Westerners pushed for more.

The Westerners also pushed one another, terrified that a commercial rival would gain some concession that would shut their traders out of the new markets. In 1853 their rivalry spilled over into Japan. Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Edo Bay and demanded the right for American steamships bound for China to refuel there. He brought just four modern ships, but they carried more firepower than all the guns in Japan combined. His ships were “

castles that moved

freely on the waters,” one amazed witness said. “What we’d taken for a conflagration on the sea was really black smoke rising out of [their] smokestacks.” Japan granted

Americans the right to trade in two ports; Britain and Russia promptly demanded—and received—the same.

Figure 10.6. Cultural dissonance: a Chinese sketch of a fire-breathing British sailor, 1839

The jockeying for position did not stop there. In an appendix to their 1842 treaty with China, British lawyers had invented a new status, “most favored nation,” meaning that anything China gave another Western power, it had to give Britain too. The treaty the United States had signed with China in 1843 included a provision allowing for renegotiation after twelve years, so in 1854 British diplomats claimed the same right. The Qing stalled and Britain went back to war.

Even the British Parliament thought this was a little much. It censured Prime Minister Palmerston; his government fell; but the voters returned him with an increased majority. In 1860 Britain and France occupied Beijing, burned the Summer Palace, and sent Looty back to Balmoral. Not to be outdone in renegotiation, America’s consul general bullied Japan into a new treaty by threatening that the alternative was for British ships to open the country to opium.

The West bestrode the world like a colossus in 1860, its reach seemingly unlimited. The ancient Eastern core, which just a century before had boasted the highest social development in the world, was becoming a new periphery to the Western core, just like the former cores in South Asia and the Americas; and North America, now heavily settled by Europeans, was pushing into the core in its own right. Responding to this massive reorganization of geography, Europeans opened still newer frontiers. Their steamships carried the white plague of settlers to South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, and returned with their holds full of grain and sheep. Africa, still largely a blank space on Western maps as late as 1870, was almost entirely under European rule by 1900.

Looking back on these years in 1919, the economist John Maynard Keynes remembered them as a golden age when

for … the [West’s]

middle and upper classes, life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth … and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world; … He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or any other formality … and could then proceed abroad to foreign quarters, without knowledge of their religion, language, or customs, bearing coined wealth upon his person, and would consider himself greatly aggrieved and much surprised at the least interference.

But things looked rather different to the novelist Joseph Conrad after he had spent much of 1890 in the Congo Basin. “

The conquest

of the earth, which mostly means taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much,” he observed in his anti-colonialist classic

Heart of Darkness

.

The Congo was certainly the extreme case: King Leopold of Belgium seized it as his personal property and made himself a billionaire by torturing, mutilating, and murdering 5 million or more Congolese

to encourage the others to provide him with rubber and ivory. It was hardly unique, though. In North America and Australia white settlers almost exterminated the natives, and some historians blame European imperialism for turning the weak monsoons of 1876–79 and 1896–1902 into catastrophes. Even though crops failed, landlords kept on exporting food to Western markets, and from China to India and Ethiopia to Brazil hunger turned to famine. Dysentery, smallpox, cholera, and the Black Death itself came in its wake, carrying off perhaps 50 million weakened people. Some Westerners raised aid for the starving; some pretended nothing was happening; and some, like

The Economist

magazine, grumbled that famine relief merely taught the hungry that “

it is the duty

of the Government to keep them alive.” Small wonder that the dying whisper of Mr. Kurtz, the evil genius whom Conrad pictured carving out a personal kingdom in the jungle, has come to stand as the epitaph of European imperialism: “

The horror! The horror!

”

*

The East avoided the worst, but still suffered defeat, humiliation, and exploitation at Western hands. China and Japan fell apart as motley crews of patriots, dissidents, and criminals, blaming their governments for everything, took up arms. Religious fanatics and militiamen murdered Westerners who strayed outside their fortified compounds and bureaucrats who appeased these intruders; Western navies bombarded coastal towns in retaliation; rival factions played the Westerners against one another. European weapons flooded Japan, where a British-backed faction overthrew the legitimate government in 1868. In China civil war cost 20 million lives before Western financiers decided that regime change would hurt returns, whereupon an “Ever-Victorious Army” with American and British officers and gunboats helped save the Qing.

Westerners told Eastern governments what to do, seized their assets, and filled their council chambers with advisers. These, not surprisingly, kept down tariffs on Western imports and prices on goods Westerners wanted to buy. Sometimes the process even made Westerners uncomfortable. “

I have seen things

that made my blood boil in the

way the European powers attempt to degrade the Asiatic nations,” Ulysses S. Grant told the Japanese emperor in 1879.

Most Westerners, however, concluded that things were just as they should be, and against this background of Eastern collapse, long-term lock-in theories of Western rule hardened. The East, with its corrupt emperors, groveling Confucians, and billion half-starved coolies, seemed always to have been destined for subjection to the dynamic West. The world appeared to be reaching its final, predestined form.

THE WAR OF THE EAST

The arrogant, self-congratulatory champions of nineteenth-century long-term lock-in theories overlooked one big thing—the logic of their own market-driven imperialism. Just as the market had led British capitalists to build up the industrial infrastructure of their own worst rivals in Germany and the United States, it now rewarded Westerners who poured capital, inventions, and know-how into the East. Westerners stacked the deck in their own favor whenever they could, but capital’s relentless quest for new profits also presented opportunities to Easterners who were ready to seize them.

The speed with which Easterners did so was astonishing. In the 1860s Chinese “self-strengthening” and Japanese “civilization and enlightenment” movements set about copying what they saw as the best of the West, translating Western books on science, government, law, and medicine into Chinese and Japanese and sending delegations to the West to look for themselves. Westerners rushed to sell their latest gadgets to Easterners, and Chinese and Japanese Gradgrinds dirtied the countryside with factories.

In a way, this was not so surprising. When Easterners grabbed at the tools that had driven Western social development so high, they were doing just the same thing that Westerners had done six centuries earlier with Eastern tools such as compasses, cast iron, and guns. But in another way, it was very surprising. The Eastern reaction to Western rule differed sharply from the reactions in the former cores in the New World and South Asia, incorporated as Western peripheries across the previous three centuries.

Native Americans never developed indigenous industries and South Asians were much slower to do so than East Asians. Some historians think culture explains this, arguing (more or less explicitly) that while Western culture strongly encourages hard work and rationality, Eastern culture does so only weakly, South Asian culture even less, and other cultures not at all. But this legacy of colonialist mind-sets cannot be right.