Why the West Rules--For Now (78 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Few Western rulers shared Qianlong’s faith in isolation. The world they lived in was not dominated by a single great empire like Qing China; rather, it was a place of squabbles and constantly shifting balances of power. As most Western rulers saw things, even if the world’s wealth was fixed, a nation could always grab a bigger slice of the pie. Every florin, franc, or pound spent on war would pay for itself, and as long as some rulers felt that way, all rulers had to be ready to fight. Western Europe’s arms race never stopped.

Europe’s merchants of death constantly improved the tools of their trade (better bayonets, prepackaged gunpowder cartridges, faster firing mechanisms), but the real breakthroughs came from organizing violence more scientifically. Discipline—things such as uniforms, agreed-on ranks, and firing squads for officers who just did what they liked (as opposed to ordinary soldiers, who had always been punished brutally)—worked wonders, and adding year-round training created fighting machines that performed complex maneuvers and fired their weapons steadily.

Such orderly dogs of war delivered more kills for the guilder. First the Dutch and then their rivals eliminated the cheap but nasty tradition of outsourcing war to private contractors who hired rabbles of killers, paid them irregularly or never, then turned them loose to extort income from civilians. War remained hell, but acquired at least a few limits.

The same was true at sea, where the curtain came down on the age of the Jolly Roger, walking the plank, and buried treasure. England led the way in a new war on piracy, which, like China’s in the sixteenth century, was as much about corruption as about swashbuckling. When the notorious Captain Morgan had ignored an English peace treaty with Spain and sacked Spanish colonies in the Caribbean in 1671, his well-placed backers had helped him to a knighthood and the governorship of Jamaica. By 1701, though, the equally notorious Captain Kidd found himself hauled to London merely for robbing an English ship, and upon arriving learned that his own well-placed backers (including the king) could or would not help him. Spending his last shilling on rum, Captain Kidd was dragged to the gallows, roaring, “

I am the innocentest

person of all!”—only for the rope to break. Once upon a time that might have saved him, but not now. A second noose did the job. By 1718, when the navy closed in on Blackbeard (Edward Teach), no one even tried to help. Blackbeard took even more killing than Kidd—five musket balls and twenty-five sword strokes—but kill him the sailors did. That year there were fifty pirate raids in the Caribbean; by 1726 there were just six. The age of rampage was over.

All this cost money, and the advances in organization depended on even greater advances in finance. No government could actually afford to feed, pay, and supply soldiers and sailors year-round, but the Dutch again found the solution: credit. It takes money to make money, and because the Netherlands had such steady income from trade and such solid banks to handle its cash, its merchant rulers could borrow bigger sums, faster, at lower interest rates, and pay them back over longer periods than spendthrift rivals.

Once more England followed the Dutch lead. By 1700 both countries had national banks, managing a public debt by selling long-term bonds on a stock exchange, with their governments calming lenders’ jitters by committing specific taxes to pay interest on the bonds. The

results were spectacular. As Daniel Defoe (the author of

Robinson Crusoe

, that epic of the new oceanic highways) explained,

Credit makes war

, and makes peace; raises armies, fits out navies, fights battles, besieges towns; and, in a word, it is more justly called the sinews of war than the money itself … Credit makes the soldier fight without pay, the armies march without provisions … and fills the Exchequer and the banks with as many millions as it pleases, upon demand.

Limitless credit meant war without end. Britain had to fight for twenty years to win the biggest slice of the trade pie from the Dutch, but that victory just paved the way for an even greater struggle. France’s rulers seemed bent on achieving the kind of land empire that had eluded the Habsburgs, and, British politicians feared, “

France will undo us

at sea when they have nothing to fear on land.” The only answer, Britain’s prime minister William Pitt (the Elder) insisted, was to “

conquer America

through Germany,” bankrolling continental coalitions to keep the French tied up in Europe while Britain snapped up its colonies overseas.

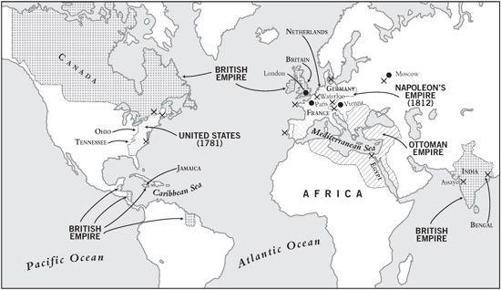

Anglo-French wars filled more than half the years between 1689, when France’s first attempt to invade England failed, and 1815, when Wellington finally defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. This epic struggle was nothing less than a War of the West, fought for domination of the European core. Great armies volleyed and charged in Germany and dug trenches in Flanders; men-of-war blasted and boarded each other off the stormy French coast and in the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean; and in the forests of Canada and Ohio, the plantations of the Caribbean, and the jungles of west Africa and Bengal, European and (especially) local allies fought dozens of bitter, self-contained little wars that added up to make the War of the West the first worldwide struggle.

There was daring and treachery enough to fill many a book, yet the real story was told in pounds, shillings, and pence. Credit constantly replenished Britain’s armies or fleets, but France could not pay its bills. “

Our bells are threadbare

with ringing of victories,” one well-placed Briton bragged in 1759, and in 1763 the exhausted French had no option but to sign away most of their overseas empire (

Figure 9.8

).

Figure 9.8. All the world’s a stage: the global setting of the War of the West, fought by Britain and its allies against France between 1689 and 1815. Crossed swords mark some of the major battles; the British Empire as it was in 1815 is marked by dots.

The War of the West, though, was barely half done. Even Britain was feeling the financial strain, and when a poorly thought-out scheme to get the American colonists to pick up part of the check for the war set off a revolt in 1776, France was there with the cash and ships that made all the difference for the rebels. Not even Britain’s credit could master determined rebels three thousand miles from home

and

another great power.

Finance could, though, take away the sting of defeat. In any reasonable world, losing America to revolutionaries who celebrated their pursuit of happiness in language inspired by the French Enlightenment should have bankrupted Britain’s Atlantic economy and ushered in a French imperium in Europe. Pitt feared as much, warning that if Britain lost he expected every gentleman in England to sell up and ship out to America, but trade and credit again came to the rescue. Britain paid down its debts, kept its fleets patrolling the sea-lanes, and went on carrying the goods Americans still needed. By 1789 Anglo-American trade was back to prerevolution levels.

For France, however, 1789 was a disaster. To win the American war Louis XVI had run up debts he could not pay, so he now convened his nobles, clergy, and rich commoners to ask for new taxes, only for the commoners to turn the Enlightenment against him, too. Proclaiming the Rights of Man (and, two years later, those of Woman), rich commoners found themselves half stage-managing and half trying to stay out of the way of an unpredictable spiral of revolt and civil war. “

Make terror

the order of the day!” the radicals shouted, then executed their king, his family, and thousands of their fellow revolutionaries.

Once again reasonable expectations were confounded. Instead of leaving Britain master of the West, the revolution opened the way for new forms of mass warfare, and for a few heady years it looked as if Napoleon, its general of genius, would finally create a European land empire. In 1805 he mustered his Grand Army for the fourth French attempt to invade Britain since 1689; “

Let us be masters

of the Channel for six hours,” he told the troops, “and we are masters of the world!”

Napoleon never got his six hours, and although he made British traders’ worst nightmares come true by shutting them out of every harbor in Europe, he could not break their financial power. In 1812 Napoleon controlled a quarter of Europe’s population and a French army was in Moscow; two years later he was out of power and a Russian

army (on the British payroll) was in Paris; and in 1815 diplomats at the great Congress of Vienna thrashed out terms that would damp down the War of the West for the next ninety-nine years.

Did all these wars in the end make much difference? In a way, yes. In 1683, on the eve of the Anglo-French conflict, Vienna was again under siege by a Turkish army, but by the time the great and the good convened there in 1815 the War of the West had pushed western European firepower, discipline, and finance far ahead of anything else in the world, and Turkish armies came no more. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 the Ottomans had to rely on Britain to throw him out, and in 1803 fewer than five thousand British troops (half of them recruited locally and trained in European musketry) would scatter ten times their number of South Asians at Assaye. The balance of military power had shifted, spectacularly, toward western Europe.

But in another way, no. Despite all the battles and bombardments, real wages kept falling after 1750. Beginning in the 1770s, a new breed of scholars, calling themselves political economists, brought all the tools of science and enlightenment to bear on the problem. The news they brought back from their researches was not good: there were, they claimed, iron laws governing humanity. First, although empire and conquest might raise productivity and income, people would always convert extra wealth into more babies. The babies’ empty bellies would then consume all the extra wealth, and, worse still, when the babies grew up and needed jobs of their own, their competition would drive wages back down to the edge of starvation.

There appeared to be no way out of this cruel cycle. Had the political economists known about the index of social development they would probably have pointed out that although the hard ceiling had been pushed up a little, it remained as hard as ever. They might have been fascinated to learn that the West’s score had caught up with the East’s in 1773, but would surely have said it did not really matter, because the iron laws forbade either score from rising much further. Political economy had proved scientifically that nothing could ever really change.

But then it did.

10

THE WESTERN AGE

WHAT ALL THE WORLD DESIRES

Once in a while a single year seems to shift the ground under our feet. In the West, 1776 was such a moment. In America a tax revolt turned into a revolution; in Glasgow, Adam Smith finished his

Wealth of Nations

, the first and greatest work of political economy; in London, Edward Gibbon’s

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

hit the bookstores and became an overnight sensation. Great men were doing great things. Yet on March 22 James Boswell—Ninth Laird of Auchinleck, thwarted man of letters, and ambitious hanger-on around the rich and famous—was to be found not in some wit-filled salon but in a coach splashing through the mud toward Soho, an estate outside Birmingham in the English Midlands (

Figure 10.1

).

From a distance Soho’s clock tower, carriageway, and Palladian façade made it look like just the kind of country house Boswell might want to visit for tea and pleasantries, but on closer approach a clattering hubbub of crashing hammers, screeching lathes, and cursing laborers dispelled any such illusions. This was no setting for a Jane Austen novel; it was a factory. And Boswell, despite his privilege and pretensions, wanted to see it, for there was nothing quite like Soho anywhere else in the world.