Why the West Rules--For Now (74 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

For nomads this was an unmitigated disaster. Those who survived the wars were increasingly hemmed in. Free movement, the foundation of their way of life, came to depend on the whims of distant emperors, and from the eighteenth century onward the once-proud steppe warriors were increasingly reduced to hired hands, thugs such as the Cossacks, deployed to keep unruly peasants in line.

For the empires, though, closing the steppe highway was a triumph. Inner Asia, so long a source of danger, became a new frontier. As nomad raids declined, a million or two Russians and five or ten million Chinese drifted from the crowded cores to new lands along the edges of the steppe frontier. Once there, those tough enough to make it carved up the landscape for farming, mining, and logging, sending raw materials and taxes back to the empires’ heartlands. Closing the steppe highway did not just avert collapse; it also began a steppe bonanza, cracking the hard ceiling that had for millennia limited social development to the low forties on the index.

OPENING THE OCEANS

As the Russians and Chinese were closing the old steppe highway, western Europeans were opening a new oceanic highway that would change history even more dramatically.

For a century after western Europeans first crossed the Atlantic and entered the Indian Ocean, their maritime empires did not seem so very unusual. Venetians had been enriching themselves by tapping Indian

Ocean trade since the thirteenth century; by sailing around Africa’s southern tip rather than haggling their way across the Turkish Empire, Portuguese sailors simply did the same thing more cheaply and quickly. In the Americas the Spaniards had entered a wholly New World, but what they did there was really quite like what the Russians would later do in Siberia.

Both Spaniards and Russians outsourced everything possible. Ivan the Terrible gave the Stroganov family a monopoly on everything east of the Urals in return for a cut of the takings; Spain’s kings gave more or less anyone who asked the right to keep whatever they could find in the Americas so long as the Habsburgs got 20 percent. In both Siberia and America tiny bands of desperadoes fanned out, scattering stockades built at their own expense across mind-boggling expanses of unmapped territory and constantly writing home for more money and more European women.

Where fur fever drove Russians, bullion fever drove Spaniards. Cortés set Spain on this path by sacking Tenochtitlán in 1521, and Francisco Pizarro speeded them further along it. In 1533 he kidnapped the Inca king Atahualpa and as ransom ordered his subjects to stuff a room twenty-two feet long, seventeen feet across, and nine feet high with treasure. Pizarro melted the accumulated artistic triumphs of Andean civilization into ingots—13,420 pounds of gold and 26,000 pounds of silver—and then strangled Atahualpa anyway.

The relatively easy pickings ran out by 1535, but dreams of El Dorado, the Golden King of a realm where treasure lay all around, kept the cutthroats coming. “

Every day

they did nothing else but think about gold and silver and the riches of the Indies of Peru,” one chronicler lamented. “They were like a man in desperation, crazy, mad, out of their minds with greed for gold and silver.”

The madness found a new outlet in 1555, when improved techniques for extracting silver suddenly made New World mining highly profitable. Output was prodigious: some fifty thousand tons of American silver reached Europe between 1540 and 1700, two-thirds of it from Potosí, a mountain in what is now Bolivia that turned out to be virtually solid ore. By the 1580s Europe’s stock of silver had doubled and the Habsburg take had grown tenfold—even though, as a Spanish visitor to Potosí claimed in 1638, “

Every peso

coin minted in Potosí has cost the life of ten Indians.” In another parallel with Russia, the

Habsburgs came to look on their conquest of the wild periphery chiefly as a way to finance wars to build a land empire in Europe. “

Potosí lives

in order to serve the imposing aspirations of Spain,” one visitor wrote. “It serves to chastise the Turk, humble the Moor, make Flanders tremble, and terrify England.”

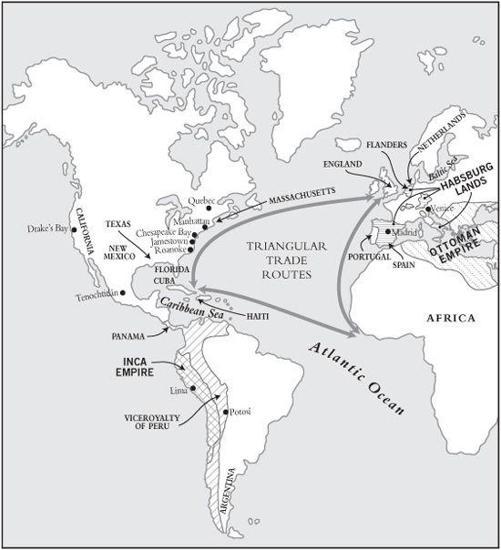

Figure 9.6. The oceanic empires, 1500–1750. The arrows show the major “triangular trades” of slaves, sugar, rum, food, and manufactured goods around the Atlantic.

The Habsburgs used most of their New World silver to pay their debts to Italian financiers, from whose hands much of the bullion made its way to China, where the booming economy needed all the silver coins it could get. “

The king of China

could build a palace with the

silver bars from Peru which have been carried to his country,” one trader thought. Yet although the Habsburg Empire exported silver and the Ming Empire imported it, they otherwise had much in common, worrying more about enlarging their own slice of the economic pie than about enlarging the pie itself. Both empires restricted overseas trade to a chosen few who held easy-to-tax state-backed monopolies.

In theory, Spain allowed just one great galleon full of silver to cross the Atlantic each year, and (again, in theory) regulated trade in other goods just as strictly. In practice, the outcome was like that along China’s troubled coasts: those excluded from official sweetheart deals created a huge black market. These “interlopers,” like China’s smuggling pirates, undersold official dealers by ignoring taxes and shooting anyone who argued.

The French, who bore the brunt of the Habsburgs’ European wars in the 1520s–30s, were first into the fray. The earliest recorded pirate attack was in 1536; by the 1550s they were common. “

Along the whole coast

of [Haiti] there is not a single village that has not been looted by the French,” one official complained in 1555. In the 1560s English smugglers also started selling duty-free slaves or landing and robbing mule trains of silver, as opportunities presented themselves. The pickings were good, and within twenty years western Europe’s wildest and most desperate men (and a few women) were flocking to join them.

Spain, like China, reacted slowly and halfheartedly. Both empires usually found that ignoring pirates was cheaper than fighting them, and only in the 1560s did Spain, like China, really push back. A decades-long global war on piracy broke out, fought with cutlass and cannon from China to Cuba (and by the Ottomans in the Mediterranean too). In 1575 Spanish and Chinese ships even collaborated against pirates off the Philippines.

By then the Ming and Ottomans had more or less won their pirate wars, but Spain was struggling with the altogether more serious threat of privateering—state-sponsored piracy. Privateers were captains whose rulers gave them licenses and sometimes even ships to plunder the Spaniards, and their nerve knew no limits. In the 1550s the ferocious French privateer Peg-Leg Le Clerc sacked Cuba’s main towns and in 1575 England’s John Oxenham sailed into the Caribbean, beached his ship near Panama, and dragged two of its cannons across the isthmus. When he reached the Pacific side he cut down trees, built a new ship,

took on a crew of runaway slaves, and for a couple of weeks terrorized Peru’s defenseless coast.

Oxenham ended up dangling from a rope in Lima, but four years later his old shipmate Francis Drake—equal parts liar, thief, and visionary; in short, the consummate pirate—was back with the even wilder plan of sailing around the bottom of South America and plundering Peru properly. Only one of his six ships made it around Cape Horn, but it was so heavily armed that it instantly established English naval supremacy in the Pacific. Drake proceeded to capture the biggest haul of silver and gold (over twenty-five tons) ever taken from a Spanish vessel, and then, realizing that he could not go back the way he had come, calmly circumnavigated the globe with his loot. Piracy paid: Drake’s backers realized a 4,700 percent return on their investment, and using just three-quarters of her share Queen Elizabeth cleared England’s entire foreign debt.

Emboldened by success, Spain’s rivals sent their own would-be conquistadors to the New World. That went less well. In an extraordinary triumph of hope over experience, France planted a colony at Quebec in 1541 in the expectation of finding gold and spices. Quebec being rather short of both, the colony failed. Nor did the next French effort prosper: copying the Spaniards even more closely, colonists settled almost next door to a Spanish fort in Florida and were promptly massacred.

The first English ventures were equally unrealistic. After terrorizing Peru in 1579 Francis Drake sailed up America’s west coast and landed in California (perhaps at the picturesque inlet near San Francisco now known as Drake’s Bay). There he informed the locals who met him on the beach that their homeland was now called Nova Albion—New England—and belonged to Queen Elizabeth; whereupon he set off again, never to return.

In 1585 Drake’s great rival Walter Raleigh (or Walter Raw Lie, as rivals liked to call him) founded his own colony, Roanoke, in what is now North Carolina. Raleigh was more realistic than Drake and did at least land actual settlers, but his plan to use Roanoke as a pirate lair for raiding Spanish shipping was disastrous. Roanoke was poorly placed, and when Drake sailed past the next year its starving colonists hitched a ride home with him. One of Raleigh’s lieutenants dropped a second party at Roanoke (he was supposed to take them to a better site on

Chesapeake Bay, but got lost). No one knows what happened to them; when their governor returned in 1590 he found everyone gone and just a single word—Croatan, their name for Roanoke—carved on a tree.

Life was cheap on this new frontier, and the lives of Native Americans especially so. Spaniards liked to joke that their imperial overlords in Madrid were so inefficient that “

if death came

from Spain, we would all live forever,” but Native Americans probably did not find that very funny. For them death

did

come from Spain. Shielded by the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, they had evolved no defenses against Old World germs, and within a few generations of Columbus’s landfall their numbers fell by at least three-quarters. This was the “Columbian Exchange” mentioned in

Chapter 6

: Europeans got a new continent and Native Americans got smallpox. Although European colonists sometimes visited horrifying cruelty on the people they encountered, death came to natives mostly unseen, as microbes on the breath or in body fluids. It also raced far ahead of the Europeans themselves, transmitted from colonists to natives and then spread inland every time an infected native met one who was still healthy. Consequently, when white men did show their faces, they rarely had much trouble dispossessing the shrunken native populations.

Wherever the land was good, colonists created what the historian and geographer Al Crosby calls “Neo-Europes”—transplanted versions of their homelands, complete with familiar crops, weeds, and animals. And where colonists did not want the land—as in New Mexico, which contained nothing, a Spanish viceroy claimed, but “

naked people

, false bits of coral, and four pebbles”—their ecological imperialism (another of Crosby’s fine phrases) transformed it anyway. From Argentina to Texas, cattle, pigs, and sheep ran off, went wild, bred herds millions strong, and took over the plains.

Better still, colonists created

improved

Europes, where instead of squeezing rent out of surly peasants they could reduce the surviving natives to bondage or—if natives were unavailable—ship in African slaves (the first are attested in 1510; by 1650 they outnumbered Europeans in Spanish America). “

Even if you are poor

you are better off here than in Spain,” one settler wrote home from Mexico, “because here you are always in charge and do not have to work personally, and you are always on horseback.”

By building improved Europes the colonists began yet another revolution in the meaning of geography. In the sixteenth century, when traditional-minded European imperialists had treated the New World primarily as a source of plunder to finance the struggle for a land empire in Europe, the oceans separating America from the Old World had been nothing but an annoyance. In the seventeenth century, though, geographical separation began to seem like a plus. Colonists could exploit the ecological differences between the New World and the Old to produce commodities that either did not exist in Europe or performed better in the Americas than at home, then sell them back to European markets. Instead of being a barrier, the Atlantic was beginning to look like a highway allowing traders to integrate different worlds.

In 1608 French settlers returned to Quebec, this time as fur traders, not treasure hunters. They flourished. English settlers at Jamestown almost starved until they discovered in 1612 that tobacco thrived in Virginia. The leaf was not as fine as what the Spaniards grew in the Caribbean, but it was cheap, and soon fortunes were being made. In 1613 Dutch fur traders settled on Manhattan, then bought the whole island. In the 1620s religious refugees who had fled England for Massachusetts got in on the act too, sending timber for ships’ masts back home. By the 1650s they were sending cattle and dried fish to the Caribbean, where sugar—white gold—was setting off a whole new frenzy. Settlers and slaves dribbled, then flooded, westward across the Atlantic, and exotic commodities and taxes washed back eastward.