Why the West Rules--For Now (93 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

For thirty years brinksmanship and blunders produced an agonizing sequence of glimpses of the outer darkness, but the worst never came to the worst. Since 1986 the number of warheads in the world has fallen by two-thirds, with further big reductions agreed upon in 2010. The thousands of weapons that the Americans and Russians still have could kill everyone on earth with megatons to spare, but Nightfall now seems far less likely than it did during the forty years of Mutual Assured Destruction. Biology, sociology, and geography continue to weave their webs; history goes on.

FOUNDATION

Asimov’s story “Nightfall” has not, so far at least, provided a very good model for explaining the onward march of history, but perhaps his

Foundation

novels can do better. Far, far in the future, says Asimov, a young

mathematician named Hari Seldon takes a spaceship to Trantor, the mighty capital of a Galactic Empire that has endured for twelve thousand years. There he delivers a scholarly paper at the Decennial Mathematics Convention, explaining the theoretical basis for a new science called psychohistory. In principle, Seldon claims, if we combine regular history, mass psychology, and advanced statistics, we can identify the forces that drive humanity and then project them forward to predict the future.

Promoted from his provincial home planet to a chair at Trantor’s greatest university, Seldon works out psychohistory’s methods. His major conclusion is that the Galactic Empire is about to fall, leading to a thirty-thousand-year dark age before a Second Empire rises. The emperor promotes Seldon to first minister, from which illustrious position he plans a think tank called the Foundation. While gathering all knowledge into an

Encyclopedia Galactica

its scholars will mastermind a secret plan to restore the empire after just one thousand years.

The

Foundation

novels have delighted science fiction fans for half a century, but Hari Seldon is a standing joke among those professional historians who have heard of him. Only in Asimov’s feverish imagination, they maintain, could knowing what has already happened tell you what is going to happen. Many historians deny that there are any big patterns to find in the past, while those who do think there may be such patterns nevertheless tend to feel that detecting them is beyond our powers. Geoffrey Elton, for instance, who held not only the Regius Chair in Modern History at Cambridge University but also famously strong opinions on all matters historical, perhaps spoke for the majority: “

Recorded history

,” he insisted, “amounts to no more than about two hundred generations. Even if there is a larger purpose in history, it must be said that we cannot really expect so far to be able to extract it from the little bit of history we have.”

I have tried to show in this book that historians are selling themselves short. We do not have to limit ourselves to the two hundred generations in which people have been writing documents. If we widen our perspective to encompass archaeology, genetics, and linguistics—the kinds of evidence that dominated my first few chapters—we get a whole lot more history. Enough, in fact, to take us back five hundred generations. From such a big chunk of time, I have argued, we really can extract some patterns; and now, like Seldon, I want to suggest that once we do this we really can use the past to foresee the future.

12

… FOR NOW

IN THE GRAVEYARD OF HISTORY

At the end of

Chapter 3

we left Ebenezer Scrooge staring in horror at his own untended tombstone. Clutching the hand of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, he cried out: “Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of the things that May be, only?”

I suggested that we might well ask the same about

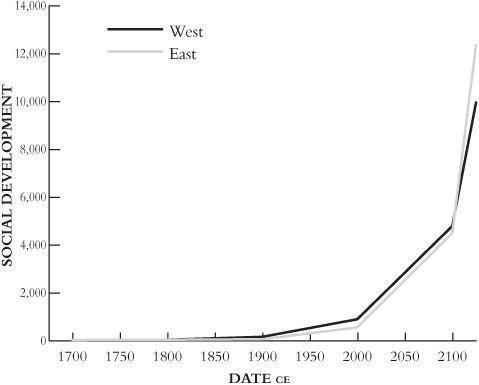

Figure 12.1

, which shows that if Eastern and Western social development keep on rising at the same speed as in the twentieth century, the East will regain the lead in 2103. But since the pace at which social development has been rising has actually been accelerating since the seventeenth century,

Figure 12.1

is really a conservative

estimate

; the graph might be best interpreted as saying that 2103 is probably the

latest

point at which the Western age will end.

Eastern cities are already as large as Western, and the gap between the total economic output of China and the United States (perhaps the easiest variable to predict) is narrowing rapidly. The strategists on America’s National Intelligence Council think China’s output will catch up with the United States’ in 2036. The bankers at Goldman Sachs think it will happen in 2027; the accountants at PricewaterhouseCoopers, in 2025; and some economists, such as Angus Maddison

of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the Nobel Prize winner Robert Fogel, opt for even closer dates (2020 and 2016, respectively). It will take longer for the East’s war-making capacity, information technology, and per capita energy capture to overtake the West’s, but it seems reasonable to suspect that after 2050 Eastern social development will catch up quickly.

Figure 12.1. Written in stone? If Eastern and Western social development scores carry on rising at the same speed as in the twentieth century, Western rule will end in 2103.

Yet nagging doubts do remain. All the expert predictions mentioned above were offered in 2006–2007, on the eve of a financial crisis that these same bankers, accountants, and economists had managed not to foresee; and we should also bear in mind that the whole point of

A Christmas Carol

is that Scrooge’s fate is

not

written in stone. “

If the courses

be departed from,” Scrooge assures the Ghost, “the ends will change,” and, sure enough, Scrooge pops out of bed on Christmas morning a new man. “He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man,” said Dickens, “as the good old City knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.”

Will the West, Scrooge-like, reinvent itself in the twenty-first century and stay on top? In this final chapter, I want to suggest a rather surprising answer to this question.

I have argued throughout this book that the great weakness of most attempts to explain why the West rules and to predict what will happen next is that the soothsayers generally take such a short perspective, looking back just a few hundred years (if that) before telling us what history means. It is rather as if Scrooge tried to learn his lessons solely by talking to the Ghost of Christmas Present.

We will do better to follow Scrooge’s actual method, hanging on the words of the Ghost of Christmas Past, or to imitate Hari Seldon, who interrogated millennia of history before peering into the Galactic Empire’s future. Like Scrooge and Seldon, we need to identify not only where current trends are taking us but also whether these trends are generating forces that will undermine them. We need to factor in the paradox of development, identify advantages of backwardness, and foresee not only how geography will shape social development but also how social development will change the meanings of geography. And when we do all these things, we will find that the story still has a twist in its tail.

AFTER CHIMERICA

We have been cursed to live in interesting times.

Since about 2000 a very odd relationship has developed between the world’s Western core and its Eastern periphery. Back in the 1840s the Western core went global, projecting its power into every nook and cranny in the world and turning what had formerly been an independent Eastern core into a new periphery to the West. The relationship between core and periphery subsequently unfolded along much the same lines as those between cores and peripheries throughout history (albeit on a larger scale), with Easterners exploiting their cheap labor and natural resources to trade with the richer Western core. As often happens on peripheries, some people found advantages in backwardness, and Japan remade itself. In the 1960s several East Asian countries followed it into the American-dominated global market and prospered, and after 1978, when it finally settled into peace, responsibility,

and flexibility, so did China. The East’s vast, poor populations and indigenous intelligentsias that had struck earlier Western observers as forces of backwardness now began to look like huge advantages. The industrial revolution was finally spreading across the East, and Eastern entrepreneurs were building factories and selling low-cost goods to the West (particularly the United States).

Nothing in this script was particularly new, and for a decade or more all went well (except for Westerners who tried to compete with low-cost East Asian goods). By the 1990s, however, manufacturers in China were discovering—as people on so many peripheries had done before them—that not even the richest core could afford to buy everything that a periphery could potentially export.

What has made the East-West relationship so unusual is the solution to this problem that emerged after 2000. Even though the average American was earning nearly ten times as much as the average Chinese worker, China effectively lent Westerners money to keep buying Eastern goods. It did this by investing some of its huge current-account surplus in dollar-denominated securities such as United States Treasury Bonds. Buying up hundreds of billions of dollars also kept China’s currency artificially cheap relative to the United States’, making Chinese goods even less expensive for Westerners.

The relationship, economists realized, was rather like a marriage in which one spouse does the saving and investing, the other does the spending, and neither partner can afford a divorce. If China stopped buying dollars, the American currency might collapse and the 800 billion United States dollars that China already held would lose their value. If, on the other hand, Americans stopped buying Chinese goods, their living standards would slide and their easy credit would dry up. An American boycott might throw China into industrial chaos, but China could retaliate by dumping its dollars and ruining the U.S. economy.

The historian Niall Ferguson and the economist Moritz Schularick christened this odd couple “

Chimerica

,” a fusion of China and America that delivered spectacular economic growth but was also a chimera—a dream from which the world eventually had to wake up. Americans could not go on borrowing Chinese money to buy Chinese goods forever. Chimerica’s ocean of cheap credit inflated the prices of every kind of asset, from racehorses to real estate, and in 2007 the bubbles

started bursting. In 2008 Western economies went into free fall, dragging the rest of the world after them. By 2009, $13 trillion of consumer wealth had evaporated. Chimerica had fallen.

By early 2010, prompt government interventions had headed off a repeat of the 1930s depression, but the consequences of Chimerica’s collapse were nonetheless enormous. In the East unemployment spiked, stock markets tumbled, and China’s economy expanded barely half as fast in 2009 as it had done in 2007. But that said, China’s 7.5 percent

growth in 2009 remained well above what economies

in the Western core could hope for even in the best years. Beijing had to find $586 billion for a stimulus package, but it at least had the reserves to cover this.

In the West, however, the damage was far worse. The United States piled a $787 billion stimulus on top of its mountain of existing debt and still saw its economy shrink by more than 2 percent in 2009. The International Monetary Fund announced that summer that it expected Chinese economic growth to rebound to 8.5 percent in 2010, while the United States would manage just 0.8 percent. Most alarming of all, the

Congressional

Budget Office forecast that the United States would not pay off the borrowing for its stimulus package until 2019, by which time the entitlements of its aging population would be dragging its economy down even further.