Why the West Rules--For Now (89 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

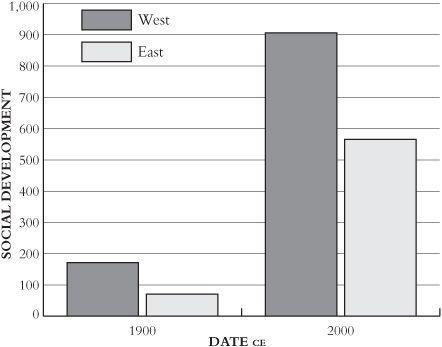

Figure 10.11. Knowing which way the wind blows: Was the twentieth century both the high point and the end point of Western rule? The West’s lead in social development increased from 101 points in 1900 to 336 in 2000, but the ratio between the Western and Eastern scores shrank by one-third, from 2.4:1 in 1900 to 1.6:1 in 2000.

________________________________

PART III

________________________________

11

WHY THE WEST RULES …

WHY THE WEST RULES

The West rules because of geography. Biology tells us why humans push social development upward; sociology tells us how they do this (except when they don’t); and geography tells us why the West, rather than some other region, has for the last two hundred years dominated the globe. Biology and sociology provide universal laws, applying to all humans in all times and places; geography explains differences.

Biology tells us that we are animals, and like all living things we exist only because we capture energy from our surroundings. When short of energy, we grow sluggish and die; when filled with it, we multiply and spread out. Like other animals, we are inquisitive but also greedy, lazy, and fearful; we are unlike other animals only in the tools we have for pursuing these moods—the faster brains, more pliable throats, and opposable thumbs that evolution gave us. Using these, we humans have imposed our wills on our environments in ways quite unlike other animals, capturing and organizing ever more energy, spreading villages, cities, states, and empires across the planet.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries plenty of Westerners thought biology was the whole answer to why the West rules. The white European race, they insisted, had evolved further than anyone

else. They were mistaken. For one thing, the genetic and skeletal evidence that I discussed in

Chapter 1

is unequivocal: there is one kind of human, which evolved gradually in Africa around a hundred thousand years ago and then spread across the globe, making older kinds of humans extinct. The genetic differences between modern humans in different parts of the world are trivial.

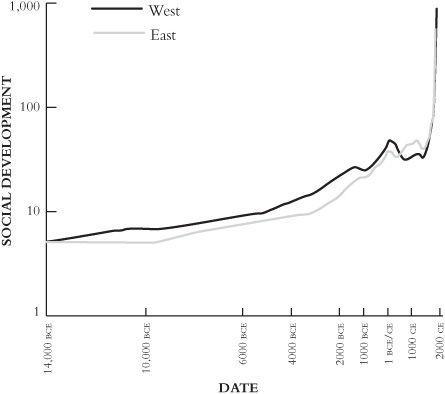

For another thing, if Westerners really were genetically superior to everyone else, the graphs of social development that fill

Chapters 4

–10 would look very different. After taking an early lead, the West would have stayed ahead. But that, of course, is not what happened (

Figure 11.1

). The West did get a head start at the end of the Ice Age, but its lead grew at some times and shrank at others. Around 550

CE

it disappeared altogether, and for the next twelve hundred years the East led the world in social development.

Figure 11.1. The shape of history revisited: Eastern and Western social development and the hard ceiling, 14,000

BCE

–2000

CE,

shown on a log-linear scale

Very few scholars nowadays propagate racist theories that Westerners are genetically superior to everyone else, but anyone who does want

to take this line will need to show that all the mettle was somehow bred out of Westerners in the sixth century

CE,

then bred back in in the eighteenth; or that Easterners bred themselves into superiority in the sixth century, then lost it in the eighteenth. That, to put it mildly, is going to be a tough job. Everything suggests that wherever we look, people—in large groups—are all much the same.

We cannot explain why the West rules without starting from biology, since biology explains why social development has kept moving up; but biology alone is not the answer. The next step is to bring in sociology, which tells us

how

social development has increased so much.

As

Figure 11.1

shows, this has not been a smooth process. In the introduction, I proposed a “Morris Theorem” (expanding an idea of the great science fiction writer Robert Heinlein) to explain the entire course of history—that change is caused by lazy, greedy, frightened people (who rarely know what they’re doing) looking for easier, more profitable, and safer ways to do things. I hope that the evidence presented in

Chapters 2

–10 has borne this out.

We have seen people constantly tinkering, making their lives easier or richer or struggling to hold on to what they already have as circumstances change, and, in the process, generally nudging social development upward. Yet none of the great transformations in social development—the origins of agriculture, the rise of cities and states, the creation of different kinds of empires, the industrial revolution—was a matter of mere tinkering; each was the result of desperate times calling for desperate measures. At the end of the Ice Age, hunter-gatherers became so successful that they put pressure on the resources that sustained them. Further efforts to find food transformed some of the plants and animals they preyed on into domesticates and transformed some of the foragers into farmers. Some farmers succeeded so well that they put renewed pressure on resources, and to survive—especially when the weather went against them—they transformed their villages into cities and states. Some cities and states succeeded so well that they, too, ran into resource problems and transformed themselves into empires (first land-based, later ruling the steppes and oceans, too). Some of these empires repeated the same cycle, putting pressure on their resources and turning themselves into industrial economies.

History is not just one damn thing after another. In fact, history is the same old same old, a single grand and relentless process of adaptations to the world that always generate new problems that call for further adaptations. Throughout this book I have called this process the paradox of development: rising social development creates the very forces that undermine it.

People confront and solve such paradoxes every day, but once in a while the paradox creates tough ceilings that will yield only to truly transformative change. It is rarely obvious what to do, let alone how to do it, and as a society approaches one of these ceilings a kind of race begins between development and collapse. Societies rarely—perhaps never—simply get stuck at a ceiling and stagnate, their social development unchanging for centuries. Rather, if they do not figure out how to smash the ceiling, their problems spiral out of control. Some or all of what I have called the five horsemen of the apocalypse break loose, and famine, disease, migration, and state collapse—particularly if they coincide with an episode of climate change—will drive development down, sometimes for centuries, even into a dark age.

One of these ceilings comes around twenty-four points on the social development index. This was the level where Western social development stalled and then collapsed after 1200

BCE.

The most important ceiling, though, which I have called the hard ceiling, comes around forty-three points. Western development hit this in the first century

CE,

then collapsed; Eastern development did the same a thousand or so years later. This hard ceiling sets a rigid limit on what agricultural empires can do. The only way to break it is to tap into the stored energy of fossil fuels, as Westerners did after 1750.

Adding sociology to biology explains much of the shape of history, telling us how people have pushed social development upward, why it rises quickly at some times and slowly at others, and why it sometimes falls. Yet even when we put them together, biology and sociology do not tell us why the West rules. To explain that, we need geography.

I have stressed a two-way relationship between geography and social development: the physical environment shapes how social development changes, but changes in social development shape what the physical environment means. Living on top of a coalfield meant very little two thousand years ago, but two hundred years ago it began meaning a lot.

Tapping into coal drove social development up faster than ever before—so fast, in fact, that soon after 1900 new fuels began to displace coal. Everything changes, including the meaning of geography.

So much for my thesis. I want to spend most of this chapter addressing some of the most obvious objections to it, but before turning to that it might be useful to recap the main details of the story that filled

Chapters 2

–10.

At the end of the Ice Age, around fifteen thousand years ago, global warming marked off a band of Lucky Latitudes (roughly 20–35 degrees north in the Old World and 15 degrees south to 20 degrees north in the New) where an abundance of large, potentially domesticable plants and animals evolved. Within this broad band, one region, the so-called Hilly Flanks of southwest Asia, was luckiest of all. Because it had the densest concentration of potential domesticates it was easier for people who lived there to become farmers than for people anywhere else. So, since people (in large groups) are all much the same, Hilly Flankers were the first to settle in villages and domesticate plants and animals, starting before 9000

BCE

. From these first farmers descended the societies of the West. About two thousand years later people in what is now China—where potential domesticates were also plentiful, though not so plentiful as in the Hilly Flanks—moved the same way; from them descend the societies of the East. Over the next few thousand years people independently began domesticating plants and/or animals in half a dozen other parts of the world, each time beginning another regional tradition.

Because Westerners were the first to farm, and because people (in large groups) are all much the same, Westerners were also the first to feel the paradox of development in a serious way and the first to learn what I have called the advantages of backwardness. Rising social development meant bigger populations, more elaborate lifestyles, and greater wealth and military power. Through various combinations of colonization and emulation, societies with relatively high social development expanded at the expense of those with lower development, and farming spread far and wide. To make farming work in new lands such as the sweltering river valleys of Mesopotamia, farmers were forced practically to reinvent it, and in the process of creating irrigation agriculture discovered advantages that made this rather backward frontier

even more fruitful than the original agricultural core in the Hilly Flanks. And some time after 4000

BCE,

with the biggest farming villages in the crowded Hilly Flanks struggling to manage, it was the Mesopotamians who worked out how to organize themselves into cities and states. About two thousand years later the same process played out in the East too, with the paradox of development exposing somewhat similar advantages of backwardness in the valleys that fed into the Yellow River basin.