Why We Broke Up (6 page)

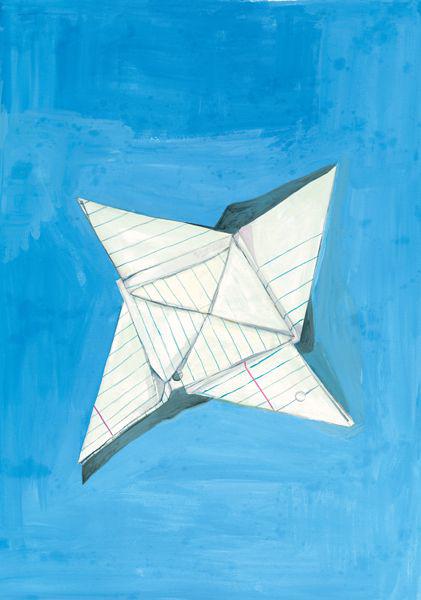

Here it is

. It took me forever to get it back to how it was, your amazing math scores all adding up in how this thing was folded. When I opened my locker Monday morning, it looked like an origami spaceship from the old Ty Limm sci-fis had landed on top of

Understanding Our Earth

, ready to unleash the electro-decimator onto Janet Bakerfield’s spinal column and destroy her brain. That’s what this did to me, too, when I unfolded the note and read it. I got all tingly and it made me stupid.

Maybe you waited for me that first morning at school, I never asked you. Maybe you wrote it last minute after second

bell and slipped it through the slats before the Olympic dash to homeroom all the jocks always do, leaving the slowpokes spinning as you bound past their backpacks like pinball toys. You didn’t know I never go to my locker until after first. You never really learned my schedule, Ed. It is a mystery, Ed, how you never knew how to find me but always found me anyway, because our paths tug-of-warred away from each other for the whole loud and tedious stretch of school, the mornings with me hanging out with Al and usually Jordan and Lauren on the right-side benches while you shot warm-up hoops on the back courts with your backpack waiting with the others and skateboards and sweatshirts in a bored heap, not a single class in common, your Early Lunch trash-dunking your apple core like it’s part of the same game, my Late Lunch on the weird corner of the lawn, hemmed in by the preppies and the hippies bickering over the airwaves with competing sound tracks except on hot days, when they truce it with reggae. In

Ships in the Night

, Philip Murray and Wanda Saxton meet in the last scene under the rainy awning, their wrong wife and fiancé finally story-lined away, and walk out together into the downpour—we know from the first scene, Christmas Eve, that both of them like walking in the rain but don’t have anybody who will do it with them—and it’s the miracle of the ending. But there are no crisscross intersections for us, a blessing now that I live in fear of bumping into you. We’d only meet on purpose, after

school before practice, you changing quick and shooing away your warm-upping teammates until you had to go, one more kiss, had to, one more, OK now really, I really really have to go.

And this note was a jittery bomb, ticking beneath my normal life, in my pocket all day fiercely reread, in my purse all week until I was afraid it would get crushed or snooped, in my drawer between two dull books to escape my mother and then in the box and now thunked back to you. A note, who writes a note like that? Who were you to write one to me? It boomed inside me the whole time, an explosion over and over, the joy of what you wrote to me jumpy shrapnel in my bloodstream. I can’t have it near me anymore, I’m grenading it back to you, as soon as I unfold it and read it and cry one more time. Because me too, and fuck you. Even now.

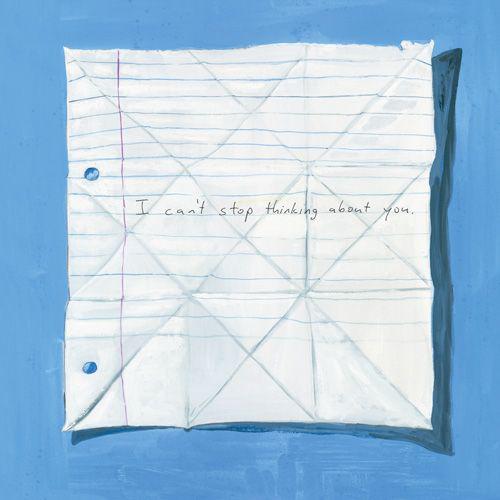

When I look at this

ripped in half, I think of the travesty of what you did and the travesty of how I didn’t care at the time. I can’t look at this while I write about it, because I’m afraid Al will see and we’ll have to talk about it all over again, like you’ve ripped it in half all over again and all over again I said nothing. You probably think this is from the night we went to the Ball, but it isn’t. You probably think it got ripped in half by accident, for no reason, just the way things happen with all the posters for all the events that end up pulped by rain or untaped by the janitors to make room for the next one, like the Holiday Formal posters that are

everywhere up now, with Jean Sabinger’s careful drawing of one of those glass ornaments which, if you look real close, has people dancing all funhouse-curved in a reflection, replacing the skulls and bats and jack-o’-lanterns on this poster, but you did it, bastard. You did it and made a scene.

Al had the posters in a huge orange stack on his lap on the right-hand benches when I arrived at school with my hair ridiculous damp and my Advanced Bio homework not done in my backpack. Jordan and Lauren were there, too, each holding—it took me a sec to get it—a roll of tape.

“Oh no,” I said.

“Morning, Min,” Al said.

“Oh no. Oh no. Al, I forgot.”

“Told you,” Jordan said to him.

“I totally forgot, and I need to find Nancie Blumineck and

beg

to copy her bio. I can’t! I can’t do it. Plus, I don’t have any tape.”

Al took out a roll of tape, he’d known all along. “Min, you swore.”

“I know.”

“You swore it to me three weeks ago over a coffee

I bought

you

at Federico’s, and Jordan and Lauren were witnesses.”

“True,” Jordan said. “We are. We were.”

“I notarized a statement,” Lauren said solemnly.

“But I

can’t

, Al.”

“You swore,” Al said, “on Theodora Sire’s gesture when she throws her cigarette into what’s-his-name’s bathwater.”

“Tom Burbank. Al—”

“You swore to help me. When I was informed that it was mandatory that I join the planning committee for the All-City All Hallows’ Ball, you didn’t have to swear to attend all the meetings like Jordan did.”

“So

boring

,” Jordan said, “my eyes are still rolled into the back of my head. These are glass replicas, Min, placed in the gaping bored holes in my skull.”

“Nor did you have to swear, as Lauren did, to hold Jean Sabinger’s hand through six drafts of the poster as each of the decorations subcommittee submitted their comments, two of which made her cry, because Jean and I still can’t talk after the Freshman Dance Incident.”

“It’s true, the crying,” Lauren said. “I have personally wiped her nose.”

“Not true,” I said.

“Well, it’s true she cried. And Jean Sabinger is a

crier

. It’s these artistic temperaments, Min.”

“All you swore to do,” Al said, “in order to get your free tickets by being a listed member of my subcommittee, was to spend one morning taping up posters.

This

morning, actually.”

“Al—”

“And don’t tell me it’s stupid,” Al said. “I am Hellman

High junior treasurer. I work in my dad’s store on weekends. My entire life is stupid. The All-City All Hallows’ Ball is stupid. Being on the planning committee for

anything

is the height of stupidity, even when, especially when, it’s mandatory. But stupidity is no excuse. Although I myself have no opinion—”

“Uh-oh,” Jordan said.

“—some would argue, for instance, that a certain amount of stupidity is exhibited by anyone who finds it necessary to chase after Ed Slaterton, and yet I abused my power just yesterday, as a member of the student council, and looked up his phone number in the attendance office at your request, Min.”

Lauren pretended to faint dead away. “

Al!

” she said, in her mother’s voice. “That is a violation of the student council honor code! It will be a very long time before I trust you ever, ever—OK, I trust you again.”

They all looked at me now. Ed, you never cared for a sec about any of them. “OK, OK, I’ll tape up posters.”

“I knew you would,” Al said, handing me his tape. “I never doubted you for a second. Pair up, people. Two will do gym through library, the others the rest.”

“I’m with Jordan,” Lauren said, taking half the stack. “I know better than to interfere with the sexual tension festival you and Min have going on this morning.”

“

Every

morning,” Jordan said.

“You think everything’s sexual tension,” I said to Lauren, “just because you were raised by Mr. and Mrs. Super-Christian. We Jews know that underlying tensions are always due to low blood sugar.”

“Yeah, well, you killed my Savior,” Lauren said, and Jordan saluted good-bye. “Don’t let it happen again.”

Al and I headed for the east doors, stepping over the legs of Marty Weiss and that Japanese-looking girl who holds hands with him by the dead planters, and we spent the morning excused from homeroom taping these posters up like they meant something, Al holding them flat and me zipping out pieces of tape over the corners. Al told me some long story about Suzanne Gane (driver’s ed, bra clasp) and then said, “So, you and Ed Slaterton. We haven’t talked much about it, really. What’s—what’s—?”

“I don’t know,” I said,

tape tape

. “He’s—it’s going well, I think.”

“OK, none of my business.”

“Not that, Al. It’s just, it’s, you know, he’s—fragile.”

“Ed Slaterton is fragile.”

“No,

we

are. I mean. Him and me, it feels that way.”

“OK,” Al said.

“I don’t know what will happen.”

“So you won’t become one of those sports girlfriends in the bleachers?

Good shot, Ed!

”

“You don’t like him.”

“I have no opinion.”

“Anyway,” I said, “they don’t call it

shot

.”

“Uh-oh, you’re learning basketball terminology.”

“Layups,” I said, “is what they say.”

“The caffeine withdrawal is going to be hard,” Al said. “No after-school coffee served in the bleachers.”

“I’m not giving up Federico’s,” I said.

“Sure, sure.”

“I’ll see you there

today

.”

“Forget it.”

“You don’t like him.”

“No opinion, I said. Anyway, tell me later.”

“But Al—”

“Min, behind you.”

“What?”

And there you were.

“Oh!”

It was too loud, I remember.

“Hey,” you said, and gave a little nod to Al that of course embarrassed him with his Halloween stack.

“Hey,” I said.

“You’re never around here,” you said.

“I’m on the subcommittee,” but you just blinked at that.

“OK, will I see you after?”

“After?”

“After school, are you going to watch me practice?”

After a sec I laughed, Ed, and tried the ambidextrous

thing of looking at Al with a

Can you believe this guy?

and you with a

Let’s talk later

at the same time. “

No

,” I said. “I’m not going to

watch you practice

.”

“Well, then call me later,” you said, and your eyes flitted around the stairwell. “Let me give you the best number,” you said, and without a thought, Ed, the travesty occurred, and you ripped down a strip from the poster we’d just put up. You didn’t think it, Ed, of course you didn’t, for Ed Slaterton the whole world, everything taped up on the wall, was just a surface for you to write on, so you took a marker from behind Al’s ear before he could even sputter, and gave me this number I’m giving back, this number I already had, this number that’s still a poster in my head that’ll never tear down, before giving back the pen and ruffling my hair and bounding down the stairs, leaving this half in my hand and the other wounded on the wall. Watching you go, Al watching you go, watching Al watching you go, and realizing I had to say you were a jerk to do that and not being able to make those words work. Because right then, Ed, the day of my last coffee after school with Al at Federico’s before, yes, goddamnit, I started to sit in the bleachers and watch you practice, the number in my hand was my ticket out of the taped-up mornings of my life, my usual friends, a poster announcing what everybody knows will happen because it happens every year.

Call me later

, you’d said, so I could call you later, at night, and it is

those nights I miss you, Ed, the most, on the phone, you beautiful bastard.