Will Eisner (13 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Arnold also felt compelled to forward all complaints about

The Spirit

. Eisner openly admitted that

The Spirit

was a work in progress, a continually developing feature that in the beginning was hit or miss. (Ironically,

The Spirit

’s first two years, in retrospect, were tame in comparison with Eisner’s later work on the feature.) Arnold, worried that a paper might decide to cancel the supplement, constantly cautioned Eisner against using material that might frighten or disturb young readers, especially violence, blood and gore, or spooky facial expressions. When critical letters arrived at Arnold’s—or Henry Martin’s—office, Eisner was certain to hear about it. Arnold would attempt to mollify an unhappy editor, and then he’d confront Eisner, who was learning on an alarmingly regular basis that his hopes of writing for an adult audience were being undermined by editors who still regarded comics as the domain of children.

Fortunately for Eisner, Arnold rarely looked at

The Spirit

until after it had been published, and newspaper editors, although unhappy with some of the content, made no attempts to censor it. But when calls or letters from angry readers came in, the complaints were passed along, often with not-so-veiled threats of cancellations. One early

Spirit

entry—a two-part episode, “Orang the Ape-Man,” involving a talking ape that falls in love with young women, including Police Commissioner Dolan’s daughter, Ellen—brought in a flood of angry responses; another, in which an undercover Adolf Hitler visits the United States, did the same. At a moment in history when America was precariously close to entering World War II, hypersensitive editors objected to any name (such as “Kurt”) that might indicate German heritage.

Eisner continued to experiment with

The Spirit

, regardless of the uproar from Busy Arnold, Henry Martin, and the newspapers subscribing to the comic book insert. He toyed with unusual panel shapes and sizes, camera angles, and the use of shadows and black ink. Eisner would eventually deem these innovations a response to necessity, to an attempt to solve problems. His experimentation with panel sizes and shapes, he said, could be traced back to his days of working on

Hawks of the Seas

, when the feature was being marketed to different-sized publications; he’d had to cut and rearrange the panels to fit the smaller-sized formats, and from this he had learned how to compress story and action as well as create a visually appealing style. His interest in movies, dating from his childhood in the Bronx, also contributed to

The Spirit

’s cinematic feel. Finally, there was Eisner’s hyperactive creative mind: never content to stay put, he was constantly on the lookout for something new.

The Spirit

’s splash page, to the exasperation of the Register & Tribune Syndicate, became Eisner’s most creative and enduring innovation. In the beginning,

The Spirit

opened like a traditional newspaper comic strip—an opening panel plunging readers into the story—but after a few weeks, Eisner tried a single-page opening that served several functions. First and foremost, it acted as a cover for

The Weekly Comic Book

, giving the insert the feeling of a magazine independent of the other sections of the Sunday paper. In addition, it cast a mood to the story and gave readers an indication of what to expect. Finally, Eisner used the splash page as a clever, creative means of placing his comic’s title in front of readers.

“I knew if I didn’t get the reader’s attention as he flipped through the Sunday newspaper, I might lose him,” Eisner said of his splash pages. “So I began to innovate on the covers. Also, I had only eight pages—seven pages, later on—to tell the story, so I had to bring the reader in very quickly, set the scene very quickly.”

Newspaper marketing analysts, their eyes set to increasing circulation numbers, weren’t impressed with Eisner’s unusual approach.

Superman

, they argued, had a standard, eye-catching logo that readers could immediately spot on the page. Newspapers carrying the comic could plaster the logo on the sides of their delivery vans, and in an extremely competitive market that found newspapers trying to find ways to bump up their readerships, advertising a popular comic strip could goose newsstand sales. The way Eisner designed his splash page, the words

The Spirit

seemed to be intentionally hidden on the page. They might be part of a building or a portion of a page designed to look like the front page of a newspaper; readers, Eisner’s critics complained, would find this confusing.

Eisner strongly disagreed. Rather than turn away from the feature, readers would look forward to each new way he’d spell out

The Spirit

on the splash page. This opening page would become the feature’s identity and its strongest selling-tool.

“My audience was transitory,” he countered. “I had to catch people on the fly, so to speak. So I began to design the front cover, the first page, as dramatically as I could, and in a way that would intrigue people into the story, and tell a little bit of the story to begin with. I would tell them the kind of story they were getting.”

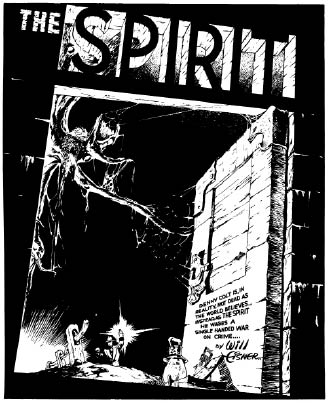

The Spirit

’s unique splash pages, such as this opening page for the December 8, 1940 entry, established Eisner’s reputation for being one of the most innovative comics artists of his time. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Eisner bore up under the criticism from Arnold and the papers, but he didn’t have an impenetrable shell. The artists in his shop watched for the telltale signs of Eisner’s mounting anger—he’d speak very softly, his pipe clenched in his teeth, then he’d speak even more softly—and the studio would lie low until it passed. He was far too busy to brood for too long.

On the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, Will Eisner was in his Tudor City studio, munching on a sandwich and listening to an opera on the radio, when an announcer broke into the broadcast with the news that Japan had attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base. That the United States was now entering its second global conflict in a quarter century (something Jerry Iger had foreseen two years earlier) came as no surprise. Servicemen and civilians alike had been gearing up for it for a long time. Like all men eligible for the draft, Eisner knew that it would be only a matter of time before he was called into the service.

“I was ambivalent,” he confessed when asked to recall his feelings about being drafted. “Everybody was very in favor of the war, particularly because of the Nazis and because of the fact that the country seemed to be in danger. So I was kind of eager to be part of it. I felt that I’d want to be a part of the war effort. On the other hand, this was a year after I had started

The Spirit

, which represented a whole new career for me. And I knew that if I went into the Army the whole thing would kind of fall apart on me.”

Prior to his being drafted into the service, Eisner had been trying to find a way to get a deferment from the military, mainly on the grounds that without him an entire business would be in jeopardy. He had been interviewed by the draft board back on July 29, and he’d shown authorities samples of his work and explained his case. The draft board demanded more—proof that without Eisner, the

Spirit

newspaper section might not survive and that a large number of people would lose their jobs if the newspaper section fell through. Busy Arnold and the Des Moines Register & Tribune Syndicate had pleaded Eisner’s case as well, and Eisner had been left alone until the United States officially entered the war.

With the declaration of war, Eisner was called up, and he was operating on borrowed time, having been granted time to make arrangements for others to cover for him while he was away. All during this period, Eisner struggled with his emotions. As a Jew, he felt strongly about Hitler and his murder of European Jews; had they not emigrated, his parents—and he himself—could have been these very people. As an American—and an artist involved with such projects as

Uncle Sam Quarterly

and

Military Comics

—he was caught up in the national furor of patriotism that immediately followed America’s entry into the war. Still, he couldn’t help wondering what would become of him and all he had worked so hard to achieve if the war dragged on for a lengthy period of time. Would he even have a career when he returned?

chapter five

A P R I V A T E N A M E D J O E D O P E

Comics—sequential art—is my medium. I regard it as much my singular medium as a writer who writes only words or the motion-picture man who writes only in movies. This is a definable, singular medium: it has perimeters and it has parameters; it has grammar; it has distinct rules; it has limitations; and it has possibilities which have not really been touched.

P

rior to his induction into the army in May 1942, Will Eisner had been living, in essence, the life of a hermit in the largest city in the United States. He went from home to office to home again, with very little time for play or socializing. He had few friends away from the office and no serious romantic involvements. His family’s money woes had robbed him of much of his adolescence, and now his young adulthood was disappearing under the avalanche of work. When he reported for processing at Fort Dix in New Jersey, he was about as far from home as he’d ever ventured. He was more mature and advanced in his adult career than most of his fellow inductees, yet at the same time far less worldly on a social level. The army gave Eisner his first real taste of freedom.

Not that the army removed him from

The Spirit

and other work demands. Before leaving for basic training, Eisner visited Busy Arnold at his Quality Comics offices in Connecticut, and the two discussed the best way to continue while Eisner was away.

“[I] talked to him about the problem of going into the army, and he said, ‘Well, we’d better move the studio up here to Stamford, to the Gurley Building,’” Eisner recalled. “So we took space right next door to Busy’s office on the same floor and began moving the shop. As a matter of fact, I remember we set up a fund to help the artists who wanted to move up there, to pay a down payment on mortgages for houses.”

Eisner’s official army portrait. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Not surprisingly, Eisner wanted to maintain some measure of control over

The Spirit

—or at the very least the Sunday installments—while he was away. He reasoned that he could write the episodes and leave the penciling and inking to others. Eisner favored Lou Fine for

The Spirit

’s artwork, and he helped Fine and his wife find a house in Stamford.

After checking in for a brief period at Fort Dix, Eisner was assigned to Aberdeeen Proving Ground near Baltimore, where he was pleased to discover that he enjoyed some celebrity status. The

Baltimore Sun

carried

The Spirit

, which impressed his fellow recruits but left his drill sergeant sour. Eisner, the sergeant scoffed, didn’t look anything at all like the Spirit, nor was he anything like his creation. “The Spirit was a heroic character and I looked a little less than that,” Eisner cracked.

Eisner remained conflicted about the war. In the months leading up to his being drafted, he and Busy Arnold had tried to find a way to get him classified as a journalist in lieu of active combat. When that failed, Arnold contacted influential connections to see if they might place Eisner in a wartime job in the States. Time changed Eisner’s thinking. He’d been through basic training, befriended other inductees, and decided that he really did want to go to Europe and fight. An office job, he decided, wouldn’t do.

His reputation and abilities scotched his chances of shipping overseas, however. He hadn’t been at Aberdeen for long before he was visited by two editors of the

Flaming Bomb

, the base newspaper. The paper needed a cartoonist, and the job was Eisner’s if he wanted it. Beginning on July 4, 1942, Eisner produced a weekly strip,

Private Dogtag

, a jokey throwaway bit that followed the exploits of Otis Dogtag, a dim-witted, bucktoothed private incapable of doing much of anything correctly. Set in Aberdeen Proving Ground,

Private Dogtag

included characters based on real soldiers, including Eisner himself and his editor, Sergeant Bob Lamar, with references to actual events in the camp. In addition to the weekly strip, Eisner illustrated column headings and advertisements and contributed occasional single-panel editorial cartoons, all at a time when he was still hanging on to his chores with

The Spirit

.

Rather than send Eisner overseas during World War II, the army had him working on such publications as the

Flaming Bomb

. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Other opportunities rolled in. The base was developing a “preventive maintenance” program, which was really nothing more than trying to convince the GIs to take care of their weapons and equipment. Maintaining equipment prevented unnecessary breakdowns, malfunctions, and waste. It was that simple. The trick was to persuade the men to do it voluntarily. The U.S. Army Ordnance Corps, looking for an artist to design posters promoting the practice, hosted a contest and Eisner won the job.

After talking to his newspaper editors over the months and seeing the way things were handled (or mishandled) by the army, Eisner had become convinced that comics could be used as an educational tool for his fellow soldiers. Part of his reasoning involved literacy, part a natural reluctance to learn something new: maintenance manuals were written in such technical language that less educated soldiers couldn’t understand them; and even if they did, they needed a

reason

to follow the directions they were given. Comics could be informal, entertaining, and easy to follow while still being educational. They could also speak the language of the soldier.

Eisner explained this line of thinking to his commanding officer, a lieutenant colonel who also oversaw the production of the

Flaming Bomb

. The lieutenant colonel liked the idea enough that, unbeknownst to Eisner, he pitched it at a meeting of higher-ups. They too responded enthusiastically, and before he knew what was happening, Eisner was being transferred to Holabird Ordnance Motor Base in Baltimore, where he was expected to develop his idea for the maintenance engineering unit.

Juggling his duties in the army and his work on

The Spirit

turned out to be a much more daunting task than Eisner had anticipated. He was still able to come up with new stories each week, but, as he’d concede later, they weren’t up to the standards he’d set back when he was working at Tudor City. As a character, the Spirit was too complex to entrust to just anyone. Eisner’s style of illustration could be imitated by several of the shop’s artists, most notably Lou Fine, but his stories were another matter. Eisner hung on to the scriptwriting and breakdowns for as long as he could, entrusting the penciling and other duties to Fine, but by November 1942, the weekly grind of writing scripts and sneaking them off to the post office had become too much. He had no alternative but to relinquish his involvement and watch Fine and the Quality Comics staff take over.

The daily

Spirit

was in even worse shape, which is difficult to imagine, given the talents working on it: Lou Fine handled the art, while Jack Cole took over the writing and, later, the art. Cole, a holdover from the Eisner & Iger shop, was a brilliant yet troubled and eccentric draftsman, perhaps as imaginative as anyone Eisner had ever worked with, possessing a powerful eye for detail and an impeccable sense of action. In his character India Rubber Man—eventually called Plastic Man—Cole had created the kind of superhero Eisner could appreciate—powerful and fluid, offbeat, humorous, and dedicated to his mission in life. Cole, a native Pennsylvanian, had moved with his wife to Manhattan, connected with Eisner and Busy Arnold, and divided his time freelancing for both.

Ironically, shortly after Eisner was drafted but before he reported for duty, Busy Arnold had pulled Cole aside and asked him to create a

Spirit

knockoff. Eisner, of course, owned the Spirit name and character, but Arnold was concerned about what he would do if something happened to Eisner. Cole’s creation—a detective named Midnight—would be his insurance. Midnight, who made his first appearance in

Smash Comics

in January 1941, was indistinguishable from the Spirit, from the blue mask and hat to the rumpled suit. Cole, however, was unhappy. Troubled by the thought of ripping off somebody he admired and respected, Cole met Eisner over dinner and explained his dilemma.

“I feel it’s not morally right,” he told Eisner.

“Well, Jack,” Eisner responded, “I can’t tell you not to do it because it’s your livelihood and, frankly, I don’t think I can sue Busy over a thing like this. He has a right to create characters for his magazines, if he wants to.”

As Eisner told it later, the two discussed Cole’s predicament for a while before coming up with an alternative. “I don’t know if it was Jack or me who got the brilliant idea to make him a funny character,” Eisner said. “That way, Jack could satisfy Busy Arnold and it’d be a totally different character. And from there, he went on to create ‘Plastic Man.’”

When it came time to find a writer/artist to work on the daily

Spirit

, Cole seemed like the perfect fit. He could write—something Lou Fine could not do—and he was very familiar with the character. It didn’t work out, however, for reasons that no one was quite able to pinpoint. In all likelihood, it was a case of vision: Cole’s Spirit was more of an action figure, whereas Eisner preferred to use the more subtle sides of the character, including humor, to add dimension to his version. That, along with the usual issues of pacing, created problems that Cole and Fine couldn’t overcome.

The daily strip dragged on until March 11, 1944, when it was mercifully put to rest. By his own admission, Eisner never felt a strong connection to it—or to the Sunday

Spirit

series that appeared during his absence.

“Except for the ownership of the concept, I felt

The Spirit

had ceased to be mine while I was away,” he said.

Will Eisner was by no means the only comic book artist to find a way to apply his talents to the war effort. The army bestowed a respect on comic book artists in the military that they hadn’t enjoyed as civilians, and rather than hand these artists a weapon and send them to the Atlantic or Pacific theaters, the army found uses for them stateside. Stan Lee designed posters, including the famous “VD? Not Me.” Nick Cardy, before seeing action that earned him two Purple Hearts, designed the patch worn by the Sixty-sixth Infantry Division. In some cases, an artist’s talents helped earn him a promotion. Eisner was promoted to the rank of corporal at the end of 1942, and just before leaving for Holabird, he tested for an administrative officer position—warrant officer, second grade. He eventually wound up a chief warrant officer.

At Holabird, Eisner was put to work on

Army Motors

, a mimeographed publication devoted to equipment maintenance. As soon as he saw a copy of the sheet, he began listing ways to improve it. To begin with, it needed to look more professional. As it stood,

Army Motors

looked as though it had been produced in a high school principal’s office; it was bound to be taken less seriously than a professionally designed publication that was well written and illustrated.

Army Motors

was the kind of product that was foisted on indifferent readers. It needed an identity, a reason for someone to pick it up and glance at its contents.

Private Joe Dope, the most inept soldier ever to pass through the United States Army, rose out of this line of thinking. Although Joe Dope and Eisner’s earlier Otis Dogtag were virtually the same character, Dogtag’s domain had been a single army base; Joe Dope would belong to everyone in the army, regardless of where he was stationed. Joe Dope would become a sort of brand name, seen on posters and in other instructional materials, as well as in

Army Motors

. For Joe Dope to work as designed, a GI had to take one look at the character and understand that this was a soldier bound for a disaster that could have been easily prevented—if, that is, he hadn’t been such a dope.