Will Eisner (29 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

His biggest issues with Warren were over the covers, which he would design and pencil and others would color. Eisner wasn’t fond of the arrangement, which he felt was a slight to his talents, but where Eisner viewed the covers from an artistic perspective, Warren approached them from a marketing angle.

“Jim had a different taste in cover art; he didn’t feel that watercolors had enough power to sell,” Eisner said. “He needed something that was brighter and more attractive. My paints are a little bit more subtle or pastel.”

As part of his agreement with Warren, Eisner kept the right of final cover approval. As a practice, he refrained from touching up or changing any of the colorings, tempting as it might have been, but there were occasions when Eisner complained to Warren or DuBay about the way an artist colored his work. One particular cover infuriated him. The colorist lit Eisner’s fuse by using what Eisner later called “circus colors,” prompting a stormy meeting with Warren and DuBay in Jim Warren’s office. “Over my dead body!” Eisner shouted.

“The cover was pretty awful,” he would remember, “and I put a stop to it very quickly.”

The first issue of Warren’s

Spirit

magazine sold 175,000 copies, rewarding Warren’s faith in the reprint’s potential and Eisner’s decision to leave Kitchen Sink Press for a bigger distributor. This was, however, the high-water mark for the magazine. The numbers fell off beginning with the second issue. Collectors gobbled it up, but the overall sales figures suggested that the Spirit, as a character, was more of a novelty than a serious contender for newsstand supremacy. Kids wanted their costumed superheroes; older readers were more attracted to the oddball material being published in

Mad

, the underground comix, and, on college campuses, the

National Lampoon

. All told, Warren published sixteen issues of

The Spirit Magazine

, plus one summer special, between April 1974 and October 1976.

The magazine might not have been an overwhelming financial success, but it served a higher purpose in Eisner’s career. With Warren, Eisner was now back in the entertainment comics business, working steadily in a field he had abandoned long ago, learning more about the purchasing habits of comics fans, and preparing himself, even if he was unaware of it at the time, for his entry into the ultimate in comics for adults—the graphic novel.

chapter eleven

A C O N T R A C T W I T H G O D

I had trouble re-reading what I had written. Being honest is like being pregnant—there’s no such thing as being “a little bit” honest. Once you start, there’s no turning back.

E

isner wasn’t finished with

The Spirit

. The sagging sales figures for the Warren reissues might have discouraged less determined artists, but after seeing enthusiastic responses from those who did pick up

The Spirit Magazine

, Eisner concluded that there still might be more life for

The Spirit

in the reprint format. He called Denis Kitchen and asked the Wisconsin publisher for his opinion.

“Are you kidding, Will?” Kitchen responded. “It may not be for newsstands, but I’m confident there is an interest in it in the collectors’ market. I’d be happy to continue it.”

Eisner and Kitchen had remained close, despite the awkwardness of Eisner’s transfer of

The Spirit

from Kitchen’s publishing house to Jim Warren’s, and the two had stayed in touch over the years. In 1974, a few months after Warren began publishing

The Spirit Magazine

, Kitchen had attended Phil Seuling’s New York convention, staying as a houseguest with the Eisners in White Plains. Eisner was brimming with ideas for ways he and Kitchen could combine forces in the business world, including a proposed new company (which he called the Small Publishers Distribution Company) that would market their work and a syndicate that would trade comics to college papers in exchange for ad space, which the syndicate would then sell to advertisers. Kitchen was both intrigued by the offers and impressed by Eisner’s business acumen.

“There is no doubt that Eisner is a tough businessman,” Kitchen wrote in his journal, “and I feel terribly naïve in comparison, but still I feel an innate trust. Eisner reinforces this feeling by his candidness and apparent affection for me. At one point he said, ‘When I see you, I see myself forty years ago.’ I think 30 is more accurate in terms of pure age, but the comment nevertheless staggers me.”

Several things became evident to Kitchen while he and Eisner talked about having Kitchen Sink Press pick up

The Spirit

. First, Eisner clearly enjoyed the rejuvenation of

The Spirit

, even if he felt strongly that he had nothing new to add to the feature, that he’d exhausted the character’s potential during the feature’s newspaper run.

“If I devoted myself totally to new stories there would be almost no time left for other new projects,” he told Denis Kitchen. “Besides, I could never fill a 64 page bimonthly without full-time working under a schedule I abandoned long ago. Then there is the consideration of the audience. Composed as it is of

1

⁄

2

collector fans, old timers and new readers I wonder what the reader reaction would be when they have the opportunity to compare the Will Eisner of 1940–1950 to today’s Eisner.”

Kitchen also realized that after spending two decades away from the comic book scene, Eisner was genuinely surprised by the potential he saw in the underground comix and the way the new artists wrote about compelling topics for older readers. Finally, he had new ideas that he wanted to pursue, and he needed an entrée—a publisher willing to let him explore these ideas on a regular basis.

The Spirit Magazine

could be a combination of reprints and new material.

Kitchen was all for it. Since the magazine had been numbered under Warren Publishing, he decided that for the sake of collectors, he would pick up where Warren left off, meaning that rather than start with #1, the first Kitchen Sink Press issue of the magazine would begin at #17. He would publish the magazine on a quarterly basis, and if Eisner had new material that he wanted to present, he’d take whatever he had to offer. The magazine’s cover would be a team effort, with Eisner providing the pencil sketch and Kitchen Sink doing the rest.

“I would expect you to provide a tight pencil drawing of a wraparound cover design for each book we publish,” Kitchen told Eisner. “I will absorb the cost of inking and coloring the covers. I have in mind Peter Poplaski … and have the utmost satisfaction that Pete can do a superb job. He has an uncanny ability to mimic styles. And if you had any reservations, I would submit inked stats for your approval.”

If anything bothered Kitchen about the arrangement, it was the selection process for the

Spirit

reprints. The Warren magazine had published the very best of the

Spirit

stories, and Eisner feared that he had only “rather lightweight” stories to offer Kitchen, especially if Kitchen published the magazine on a bimonthly basis, which was his early projection. Kitchen had never seen Eisner’s archives, and he had no idea what might be available for reprinting, so every shipment from Eisner became a new adventure—and not always for the better.

“It was a hodgepodge,” Kitchen said of the selections sent to his Wisconsin-based offices from Eisner’s office in New York. “He had his brother, Pete, working for him, and Pete would pick the stories. Sometimes he would break up stories that were two or three parts. It was frustrating. We started to get fan complaints, and Will confessed that he really didn’t have that much memory of which stories belonged together and should have been reprinted together.”

That was the downside. On the positive side, the publication’s magazine-sized format, similar to the Warren format, meant larger panels that accentuated the exquisite artwork and made the lettering that much easier to read. The splash pages, always a high point in any given installment, were all the more impressive, especially on the creamy white paper that Kitchen used in his magazine—a stark contrast to the less expensive paper used by Warren.

The Spirit

had never looked so good.

As promised, Eisner delivered a variety of non-

Spirit

material to flesh out each issue. He submitted reprints of

Lady Luck

, the feature that had appeared in the

Spirit

Sunday comic book, as well as reprints of Jules Feiffer’s

Clifford

, a clever, sardonic comic featuring precocious kids that pre-dated Charles Schulz’s

Peanuts

.

Clifford

, like

Lady Luck

and Bob Powell’s

Mr. Mystic

, had been part of the Sunday comic book. In future years, Eisner would broaden the magazine’s scope by serializing his graphic novels, writing a series of instructional pieces on sequential art, and conducting workshop interviews with leading comic book artists under the heading “Shop Talk.” If there were any doubts about Eisner’s return to the comics arena, they were settled in the magazine, which found him moving forward while offering up hefty selections from his past.

One might imagine that for a financially secure man hitting sixty, Eisner might have considered his commitment to

The Spirit Magazine

more than enough work to keep him occupied. But he was only getting started. With obligations to American Visuals and

P

*

S

magazine no longer part of his daily routine, Eisner was free to pursue projects that he might otherwise have had to put aside. He liked the idea of publishing a book of prose, and with the Spirit back in circulation, he used the character’s newfound popularity to knock off

The Spirit’s Casebook of True Haunted Houses and Ghosts

, a book of paranormal tales narrated by the Spirit, lavishly illustrated, and published by Eisner’s newly created company, Poorhouse Press.

The press was another of Eisner’s innovations with business roots dating back to his days in the old comic book studios. He wasn’t interested in publishing his non-comics work in the traditional way, which amounted to a loss of creative and financial control. Rather than going through the usual submission and production processes, Eisner could approach a publisher with a finished book, written and illustrated and laid out the way he wanted to see it in print, and upon accepting the project under consideration, the publisher would print and distribute the book, giving Eisner a better cut of the profits than the standard royalty rates. The publishing house imprint also enabled Eisner to market his books wherever he chose, he would no longer be tied down to a particular house.

According to Ann Eisner, the company’s name was a humorous reference to the uncertainty and risks of the publishing business. “They had to make up a name for it,” she said of the publishing imprint, “and Will said, ‘Well, this is the best way I know of going to the poorhouse,’ so he decided to call it Poorhouse Press.”

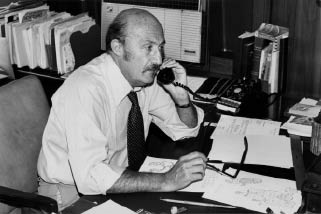

Eisner, shown here in his Manhattan office, took great pride in his business acumen, often joking that he kept one foot at the drawing table and one foot under his desk. His skills in negotiating contracts kept him from experiencing the kind of money and ownership troubles that plagued most of the early comics artists. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

All joking aside, Poorhouse Press was a safe enterprise. Between 1974 and 1985, Eisner cranked out every type of novelty book imaginable—more than twenty all told, most published by Poorhouse Press, with an occasional offering to another house, such as Baronet Press, Scholastic Books, or Bantam—bearing such titles as

Gleeful Guide to Living with Astrology

,

Gleeful Guide to Communicating with Plants to Help Them Grow

,

Gleeful Guide to Occult Cookery

, and

How to Avoid Death & Taxes, and Live Forever

. There were also two instructional books (

Comics and Sequential Art

and

Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative

), joke books, and even an illustrated bartender’s guide and

Robert’s Rules of Order

. The

Spirit Coloring Book

gave young artists the chance to provide the color to some of the comic’s best-known splash pages. Eisner employed assistants and co-writers on many of the projects and treated the books, if not their subjects, seriously, requiring the same quality that he demanded in his other, more ambitious work. But he never regarded them as anything other than a means to make money.

Denis Kitchen recalled a time, not long after he’d begun reprinting

The Spirit

in magazine format, when he was chiding Eisner for his Poorhouse Press and Scholastic Books projects. “I said to him, ‘Will, what are you doing that stuff for? Fans don’t want to see this stuff.’ He picked up one of those paperbacks that I thought was schlocky, and said, ‘This sold forty thousand copies. This made my mother very happy.’ Then he picked up

A Contract with God

and said, ‘This made my father very happy.’ He never let one prevail. Had he been strictly business, he never would have created the stuff he’s justly famous for, but you could argue that had he just been focused on the art, he wouldn’t have had the success, because it was the business side of him that negotiated the much better deals.”

Eisner wasn’t speaking literally when he held up his books and spoke of his parents’ reactions to them. Neither, in fact, had lived to see him reach his peak in international acclaim. Fannie Eisner died in 1964 at age seventy-two, long before the birth of Poorhouse Press and her son’s big push in commercial publishing, at a time when he was still working at

P

*

S

magazine and going through the ups and down of American Visuals. Sam Eisner, a dreamer until the end, passed away in 1968 at age eighty-two, a decade before the publication of

A Contract with God

and the ensuing praise of his son’s graphic novels. Sam never abandoned his passion for art and was painting landscapes, some on a very large scale, as though he were trying to express the breadth of the dreams he’d never given up well into his old age.

* * *

A much bigger—and more time-consuming—occupation materialized from an unexpected source: the School of Visual Arts, a Manhattan-based facility specializing in training students in fine art, commercial art, photography, and filmmaking. The school had discontinued its courses in comics art until a couple of students requested that such courses be offered again. Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman were the first two artists recommended for teaching positions.

“I always read that if you wanted to be a cartoonist, go to the School of Visual Arts,” recalled Batton Lash, a School of Visual Arts alumnus who went on to a successful career in comics. “Once I got there, I realized they had dropped their cartooning classes. I had met a lot of other like-minded students who went to the school for the same reason I did. We talked to Tom Gill, the artist for

The Lone Ranger

, who was head of the alumni department, and he went to the president of the school and proposed that they reinstate the cartooning classes. The school decided to start them again, and they asked Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner if they’d like to teach, and both of them said yes. It was a very exciting time.”

Eisner loved the idea of teaching a class. He’d given many young artists their starts, of course, and he’d taught a brief course at Sheridan College in Ontario in 1974. He’d enjoyed the experience. He and the class had created a new

Spirit

adventure entitled “The Invader,” and he’d found that he liked sharing tips, business advice, artistic shortcuts, and ideas with aspiring cartoonists. He didn’t appreciate the fact that so many putative comics artists were interested only in learning how to draw superheroes in order to land jobs with DC or Marvel, but he could also remember a time, back in his youth, when he was creating similar characters to order for Busy Arnold and others.