Words Can Change Your Brain (13 page)

Read Words Can Change Your Brain Online

Authors: Andrew Newberg

Sustained eye contact initiates an “approach” reaction in the brain and signals that the parties are interested in having a social engagement.

10

But if one person averts their eyes, it signals an “avoidance” response to the viewer.

11

An averted gaze also sends a neurological clue to the observer that the person may be hiding something or lying.

12

But what that something is, we cannot discern unless we engage the person in a dialogue. For example, the person may feel a romantic attraction, but the fact that they are married can make the eye contact uncomfortable. Or perhaps the person is really busy and doesn’t have time to initiate a social exchange. People with social anxiety will also avoid eye contact with others.

13

Eye contact is essential for the communication process, but the degree of contact can be influenced by the culture in which we’re raised.

14

Thus we have to take many factors into consideration if we want to use our eyes to build conversational trust.

It’s also not actually the eyes that communicate but the muscles surrounding them. If you pay specific attention to the movements of a person’s eyelids and eyebrows, you’ll receive vital information about their emotional state, especially about feelings of anger, sadness, fear, or contempt. Happiness and contentment are more difficult to discern, and a fully relaxed face can give the viewer the impression that you’re not very interested in them.

Let’s try a little experiment. Go to a mirror and take a few minutes to relax and breathe deeply. Scrunch up all the muscles in your face and then relax them. Do this several times and pay attention to the emotional messages that seem to be imparted. A tense face can convey anger, disgust, or disdain, but if you raise your eyebrows and open your mouth as wide as you can, depending on the muscles you use and how tight or relaxed they are, you can generate a variety of emotional messages, ranging from fear to surprise to terror.

Again relax your face muscles and just gaze at yourself for three or four minutes, paying attention to the thoughts and feelings that arise. If you begin to feel uncomfortable, stay with the exercise as you observe the feelings that come up. It should only take a few moments before the discomfort fades away.

Next see if you can consciously make faces that express the anger, sadness, and fear. If you use your memory of past events, you may discover that your face will reflect a deeper and more authentic emotional state. In fact, our emotional memories can stimulate the same muscular contractions that occurred when we experienced the real event.

Now experiment with different positive emotions: happiness, pleasure, contentment, peacefulness. Are they easier or harder to express? Again pay close attention to the inner speech that occurs with each expression you make. Finally, try emulating the expressions of shame, guilt, curiosity, boredom, and surprise. According to facial expression expert Paul Ekman, the more you feel the underlying emotions, the more you train your brain to both recognize and express them when you engage in a dialogue with others.

15

Most of us are not aware of the expressions we convey to others, nor do we give much attention to the expressions on other peoples’ faces. Thus we often mistake one emotion for another. But even an excellent reader of micro-expressions—emotional cues nonverbally communicated in less than a second—knows that these are just clues and that they have to be validated through deeper conversation. It’s also important to remember that when a conversation becomes intense, there can be so many internal experiences going on that the messages our face imparts become blurred.

16

We recommend that you do a similar experiment with your family members and friends. As in a game of charades, see if you can guess what emotional expression the other person is displaying. These exercises will help you to become more aware of the nonverbal messages we constantly send to one another. These exercises will also make you feel more comfortable with gazing intently at others while they are talking to you.

The Power of Gazing

There’s one more experiment we’d like you to try with a partner, colleague, or friend. All you need to do is to gaze into each other’s eyes for about five minutes. Most people will begin to feel uncomfortable after thirty seconds, but we want you to ignore the impulse to turn your eyes away. Instead sit with the discomfort and observe it, watching all the thoughts and feelings that are stirred up. Then take a few deep breaths and consciously relax your face, shoulders, and neck as you continue to gaze at your partner. When you’ve completed this exercise, talk about your experiences with each other.

This is a core exercise in our Compassionate Communication training program because it’s essential to learn how to pay close attention to the other person’s facial expressions throughout a conversation. We normally have people pair up with someone they don’t know well and gaze at each other for a minute. Then we ask them to pair up with a different partner and try it again. Each time, it becomes easier, but it usually takes three or four rounds of gazing into different people’s eyes before everyone in the group feels comfortable.

In order to succeed at this, you have to soften the muscles around your eyes. Otherwise your gaze will look more like a hardened stare. That type of gazing actually causes stress on the heart and will be perceived by others as a threat.

17

The result: the other person will avert their eyes, a signal that they are feeling discomfort. It’s also a sign that trust is fading away.

There’s another type of gaze, one that immediately stimulates a deep sense of trust and intimacy in the other person’s brain. This gaze can’t be faked because it involves involuntary muscles. The eyes are soft, and they reflect a sense of inner contentment and peace, but the expression also involves a specific type of smile, so let’s take a few minutes to explore the language of the mouth. Then, toward the end of this chapter, we’ll teach you how to generate a facial expression that reflects your inner feelings of cooperation and communication, an expression that will stimulate a deep level of trust in nearly anyone who observes your face.

The Language of the Lips

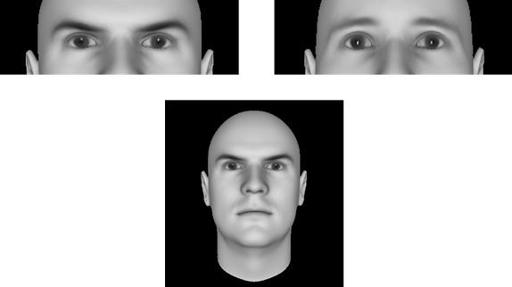

When it comes to developing empathetic trust, the eyes only tell part of the story. The other key facial expression concerns the mouth, for no matter how soft your eye gaze may be, even the slightest frown will convey a message of sadness or contempt, as the left-hand photo below illustrates. Fear is primarily communicated by the eye muscles,

18

but the slightest smile can neurologically communicate a feeling of peacefulness, contentment, and satisfaction, as the photo on the right demonstrates.

When we gaze at another person’s face, the brain identifies a range of possible emotions in the eyes, and it does the same for the mouth. Indeed, as Ekman has documented, a single person can generate over ten thousand facial expressions, and many of them will trigger a specific neurological response in the observer’s brain. With so many possibilities (and so little room in that window of consciousness known as working memory), the brain makes an educated guess as to what the other person is actually feeling.

The brain also looks for inconsistencies. If a person is lying or experiencing confusion, the eyes and the mouth can impart emotions that seem to conflict with each other. For example, in the picture above, on the left, the mouth could be expressing anger, sadness, or disgust. But if you combine that mouth with the eyes in the left-hand photo below, the emotion becomes clearer, conveying a sense of sternness.

You’ll still need other clues, like tone of voice, to tell if the person is irritated, contemptuous, or just concentrating very hard, but you can sense how the brain works to rapidly build an opinion—right or wrong—about what that individual is feeling or thinking.

The Language of Sadness

When it comes to generating neural resonance between two people, Ekman found that the most powerful facial expression is sadness. In fact, the more a person’s face expresses suffering or pain, the more the compassion circuits are stimulated in the brain of someone looking at them. However, expressing sadness in front of another person often makes one feel vulnerable, so most of us cover up our hurt by putting on an expression of anger. It’s a bad strategy, for as we’ve been documenting, anger tends to generate greater irritability, which leads to greater conflict. Thus it is always in our best interest to communicate our feelings of sadness and hurt and to suppress our defensive urge to get mad.

Just notice the feelings that are evoked when you look at the picture below. It should stir up many deep feelings, but anger won’t be one of them. Interestingly, the brain tends to respond more compassionately when we see a child suffering, perhaps because we recognize the helplessness of the victim.

Ekman recommends that we train ourselves to express sadness, and it’s rather easy to do. Just take a moment to remember a time when you felt particularly sad, and notice how the feeling affects the muscles around your eyes, mouth, and cheeks. Deliberately increase the feeling, letting it grow as strong as it can, and notice how it affects your thoughts.

Next stand in front of a mirror and see if you can duplicate the expression of the little girl above. Ekman suggests that you pull down the corners of your mouth and raise your cheeks as if you’re squinting. Then look down, pull your eyebrows together, and let your eyelids droop.

Then, when you engage in conversations with other people, consciously try to mirror their facial expressions. As the research in these chapters has documented, the more you emulate the body movements and facial expressions of the person you’re conversing with, the more your brain will resonate with theirs. You’ll both feel more connected and empathetic, and this will generate deep trust.

The only emotion you don’t want to mirror is the other person’s anger. In this case we recommend that you turn your attention inward and focus on staying as relaxed and calm as possible. Use your imagination and immerse yourself in pleasant feelings or memories and try to generate as much kindness and compassion as you can for the person who is frustrated and mad. If you can’t do this—if you feel your temper rising—call for a time-out and take a break, even if the other person objects. When they calm down, you can resume the conversation on a more positive note.

A Face Is a Face Is a Face

Can a robot use facial expressions and body language to win your trust? Yes, as researchers at MIT have proven with the creation of Nexi, the world’s first social robot. When “she” moves her mechanical eyebrows, eyelids, and lower jaw, your brain will emotionally respond in much the same way as to a person.

19