World Order (4 page)

Authors: Henry Kissinger

Most representatives had come with eminently practical instructions

based on strategic interests. While they employed almost identical high-minded phrases about achieving a “peace for Christendom,” too much blood had been spilled to conceive of reaching this lofty goal through doctrinal or political unity. It was now taken for granted that peace would be built, if at all, through balancing rivalries.

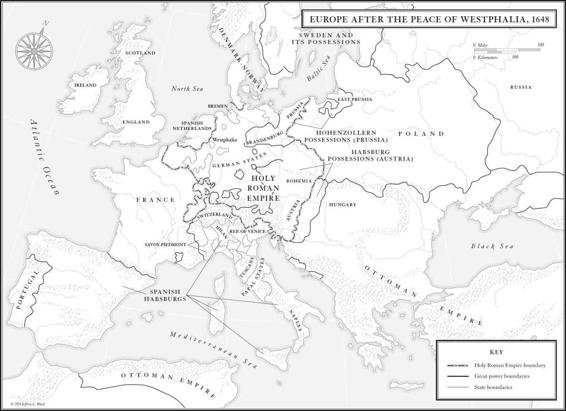

The Peace of Westphalia that emerged from these convoluted discussions is probably the most frequently cited diplomatic document in European history, though in fact no single treaty exists to embody its terms. Nor did the delegates ever meet in a single plenary session to adopt it. The peace is in reality the sum of three separate complementary agreements signed at different times in different cities. In the January 1648 Peace of Münster, Spain recognized the independence of the Dutch Republic, capping an eight-decades-long Dutch revolt that had merged with the Thirty Years’ War. In October 1648, separate groupings of powers signed the Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück, with terms mirroring each other and incorporating key provisions by reference.

Both of the main multilateral treaties

proclaimed their intent as “a Christian, universal, perpetual, true, and sincere peace and friendship” for “the glory of God and the security of Christendom.” The operative terms were not substantially different from other documents of the period. Yet the mechanisms through which they were to be reached were unprecedented. The war had shattered pretensions to universality or confessional solidarity. Begun as a struggle of Catholics against Protestants, particularly after France’s entry against the Catholic Holy Roman Empire it had turned into a free-for-all of shifting and conflicting alliances. Much like the Middle Eastern conflagrations of our own period, sectarian alignments were invoked for solidarity

and motivation in battle but were just as often discarded, trumped by clashes of geopolitical interests or simply the ambitions of outsized personalities. Every party had been abandoned at some point during the war by its “natural” allies; none signed the documents under the illusion that it was doing anything but advancing its own interests and prestige.

Paradoxically, this general exhaustion and cynicism

allowed the participants to transform the practical means of ending a particular war into general concepts of world order. With dozens of battle-hardened parties meeting to secure hard-won gains, old forms of hierarchical deference were quietly discarded. The inherent equality of sovereign states, regardless of their power or domestic system, was instituted. Newly arrived powers, such as Sweden and the Dutch Republic, were granted protocol treatment equal to that of established great powers like France and Austria. All kings were referred to as “majesty” and all ambassadors “excellency.” This novel concept was carried so far that the delegations, demanding absolute equality, devised a process of entering the sites of negotiations through individual doors, requiring the construction of many entrances, and advancing to their seats at equal speed so that none would suffer the ignominy of waiting for the other to arrive at his convenience.

The Peace of Westphalia became a turning point in the history of nations because the elements it set in place were as uncomplicated as they were sweeping. The state, not the empire, dynasty, or religious confession, was affirmed as the building block of European order. The concept of state sovereignty was established. The right of each signatory to choose its own domestic structure and religious orientation free from intervention was affirmed, while

novel clauses

ensured that minority sects could practice their faith in peace and be free from the prospect of forced conversion. Beyond the immediate demands of the moment, the principles of a system of “international relations” were taking shape, motivated by the common desire to avoid

a recurrence of total war on the Continent. Diplomatic exchanges, including the stationing of resident representatives in the capitals of fellow states (a practice followed before then generally only by Venetians), were designed to regulate relations and promote the arts of peace. The parties envisioned future conferences and consultations on the Westphalian model as forums for settling disputes before they led to conflict. International law, developed by traveling scholar-advisors such as Hugo de Groot (Grotius) during the war, was treated as an expandable body of agreed doctrine aimed at the cultivation of harmony, with the Westphalian treaties themselves at its heart.

The genius of this system, and the reason it spread across the world, was that its provisions were procedural, not substantive. If a state would accept these basic requirements, it could be recognized as an international citizen able to maintain its own culture, politics, religion, and internal policies, shielded by the international system from outside intervention. The ideal of imperial or religious unity—the operating premise of Europe’s and most other regions’ historical orders—had implied that in theory only one center of power could be fully legitimate. The Westphalian concept took multiplicity as its starting point and drew a variety of multiple societies, each accepted as a reality, into a common search for order. By the mid-twentieth century, this international system was in place on every continent; it remains the scaffolding of international order such as it now exists.

The Peace of Westphalia did not mandate a specific arrangement of alliances or a permanent European political structure. With the end of the universal Church as the ultimate source of legitimacy, and the weakening of the Holy Roman Emperor, the ordering concept for Europe became the balance of power—which, by definition, involves ideological neutrality and adjustment to evolving circumstances. The nineteenth-century British statesman Lord Palmerston expressed its basic principle as follows: “

We have no eternal allies

, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.” Asked to define these interests more specifically in the form of an official “foreign policy,” the acclaimed steward of British power professed, “

When people ask me

… for what is called a policy, the only answer is that we mean to do what may seem to be best, upon each occasion as it arises, making the Interests of Our Country one’s guiding principle.” (Of course this deceptively simple concept worked for Britain in part because its ruling class was trained in a common, almost intuitive sense of what the country’s enduring interests were.)

Today these Westphalian concepts are often maligned as a system of cynical power manipulation, indifferent to moral claims. Yet the structure established in the Peace of Westphalia represented the first attempt to institutionalize an international order on the basis of agreed rules and limits and to base it on a multiplicity of powers rather than the dominance of a single country. The concepts of

raison d’état

and the “national interest” made their first appearance, representing not an exaltation of power but an attempt to rationalize and limit its use. Armies had marched across Europe for generations under the banner of universal (and contradictory) moral claims; prophets and conquerors had unleashed total war in pursuit of a mixture of personal, dynastic, imperial, and religious ambitions. The theoretically logical and predictable intermeshing of state interests was intended to overcome the disorder unfolding in every corner of the Continent. Limited wars over calculable issues would replace the era of contending universalisms, with its forced expulsions and conversions and general war consuming civilian populations.

With all its ambiguities, the balancing of power was thought an improvement over the exactions of religious wars. But how was the balance of power to be established? In theory, it was based on realities; hence every participant in it should see it alike. But each society’s perceptions are affected by its domestic structure, culture, and history and by the overriding reality that the elements of power—however

objective—are in constant flux. Hence the balance of power needs to be recalibrated from time to time. It produces the wars whose extent it also limits.

With the Treaty of Westphalia, the papacy had been confined to ecclesiastical functions, and the doctrine of sovereign equality reigned. What political theory could then explain the origin and justify the functions of secular political order?

In his

Leviathan,

published in 1651, three years after the Peace of Westphalia, Thomas Hobbes provided such a theory. He imagined a “state of nature” in the past when the absence of authority produced a “war of all against all.” To escape such intolerable insecurity, he theorized, people delivered their rights to a sovereign power in return for the sovereign’s provision of security for all within the state’s borders. The sovereign state’s monopoly on power was established as the only way to overcome the perpetual fear of violent death and war.

This social contract in Hobbes’s analysis did

not

apply beyond the borders of states, for no supranational sovereign existed to impose order. Therefore:

Concerning the offices of one sovereign to another

, which are comprehended in that law which is commonly called the law of nations, I need not say anything in this place, because the law of nations and the law of nature is the same thing. And every sovereign hath the same right, in procuring the safety of his people, that any particular man can have, in procuring the safety of his own body.

The international arena remained in the state of nature and was anarchical because there was no world sovereign available to make it

secure and none could be practically constituted. Thus each state would have to place its own national interest above all in a world where power was the paramount factor. Cardinal Richelieu would have emphatically agreed.

The Peace of Westphalia in its early practice implemented a Hobbesian world. How was this new balance of power to be calibrated? A distinction must be made between the balance of power as a fact and the balance of power as a system. Any international order—to be worthy of that name—must sooner or later reach an equilibrium, or else it will be in a constant state of warfare. Because the medieval world contained dozens of principalities, a practical balance of power frequently existed in fact. After the Peace of Westphalia, the balance of power made its appearance as a system; that is to say, bringing it about was accepted as one of the key purposes of foreign policy; disturbing it would evoke a coalition on behalf of equilibrium.

The rise of Britain as a major naval power by early in the eighteenth century made it possible to turn the facts of the balance of power into a system. Control of the seas enabled Britain to choose the timing and scale of its involvement on the Continent to act as the arbiter of the balance of power, indeed the guarantor that Europe would have a balance of power at all. So long as England assessed its strategic requirements correctly, it would be able to back the weaker side on the Continent against the stronger, preventing any single country from achieving hegemony in Europe and thereby mobilizing the resources of the Continent to challenge Britain’s control of the seas. Until the outbreak of World War I, England acted as the balancer of the equilibrium. It fought in European wars but with shifting alliances—not in pursuit of specific, purely national goals, but by identifying the national interest with the preservation of the balance of power. Many of these principles apply to America’s role in the contemporary world, as will be discussed later.

There were in fact two balances of power

being conducted in

Europe after the Westphalian settlement: The overall balance, of which England acted as a guardian, was the protector of general stability. A Central European balance essentially manipulated by France aimed to prevent the emergence of a unified Germany in a position to become the most powerful country on the Continent. For more than two hundred years, these balances kept Europe from tearing itself to pieces as it had during the Thirty Years’ War; they did not prevent war, but they limited its impact because equilibrium, not total conquest, was the goal.

The balance of power can be challenged in at least two ways: The first is if a major country augments its strength to a point where it threatens to achieve hegemony. The second occurs when a heretofore-secondary state seeks to enter the ranks of the major powers and sets off a series of compensating adjustments by the other powers until a new equilibrium is established or a general conflagration takes place. The Westphalian system met both tests in the eighteenth century, first by thwarting the thrust for hegemony by France’s Louis XIV, then by adjusting the system to the insistence of Prussia’s Frederick the Great for equal status.

Louis XIV took full control of the French crown in 1661 and developed Richelieu’s concept of governance to unprecedented levels. The French King had in the past ruled through feudal lords with their own autonomous claims to authority based on heredity. Louis governed through a royal bureaucracy dependent entirely on him. He downgraded courtiers of noble blood and ennobled bureaucrats. What counted was service to the King, not rank of birth. The brilliant Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, son of a provincial draper, was charged with unifying the tax administration and financing constant war. The memoirs of Saint-Simon, a duke by inheritance and man of letters, bear bitter witness to the social transformation: