World Order (9 page)

Authors: Henry Kissinger

The Congress of Vienna found it relatively easy to agree on a definition of the overall balance. Already during the war—in 1804—then British Prime Minister William Pitt had put forward a plan to rectify what he considered the weaknesses of the Westphalian settlement. The Westphalian treaties had kept Central Europe divided as a way

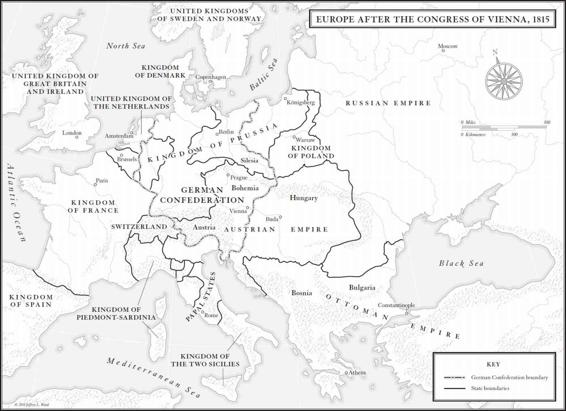

to enhance French influence. To foreclose temptations, Pitt reasoned, “great masses” had to be created in Central Europe to consolidate the region by merging some of its smaller states. (“Consolidation” was a relative term, as it still left thirty-seven states in the area covered by today’s Germany.) The obvious candidate to absorb these abolished principalities was Prussia, which originally preferred to annex contiguous Saxony but yielded to the entreaties of Austria and Britain to accept the Rhineland instead. This enlargement of Prussia placed a significant power on the border of France, creating a geostrategic reality that had not existed since the Peace of Westphalia.

The remaining thirty-seven German states were grouped in an entity called the German Confederation, which would provide an answer to Europe’s perennial German dilemma: when Germany was weak, it tempted foreign (mostly French) interventions; when unified, it became strong enough to defeat its neighbors single-handedly, tempting them to combine against the danger. In that sense Germany has for much of history been either too weak or too strong for the peace of Europe.

The German Confederation was too divided to take offensive action yet cohesive enough to resist foreign invasions into its territory. This arrangement provided an obstacle to the invasion of Central Europe without constituting a threat to the two major powers on its flanks, Russia to the east and France to the west.

To protect the new overall territorial settlement, the Quadruple Alliance of Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia was formed. A territorial guarantee—which was what the Quadruple Alliance amounted to—did not have the same significance for each of the signatories. The level of urgency with which threats were perceived varied significantly. Britain, protected by its command of the seas, felt confident in withholding definite commitments to contingencies and preferred waiting until a major threat from Europe took specific shape. The continental countries had a narrower margin of safety, assessing that their survival

might be at stake from actions far less dramatic than those causing Britain to take alarm.

This was particularly the case in the face of revolution—that is, when the threat involved the issue of legitimacy. The conservative states sought to build bulwarks against a new wave of revolution; they aimed to include mechanisms for the preservation of legitimate order—by which they meant monarchical rule. The Czar’s proposed Holy Alliance provided a mechanism for protecting the domestic status quo throughout Europe. His partners saw in the Holy Alliance—subtly redesigned—a way to curb Russian exuberance. The right of intervention was limited because, as the eventual terms stipulated, it could be exercised only in concert; in this manner, Austria and Prussia retained a veto over the more exalted schemes of the Czar.

Three tiers of institutions buttressed the Vienna system: the Quadruple Alliance to defeat challenges to the territorial order; the Holy Alliance to overcome threats to domestic institutions; and a concert of powers institutionalized through periodic diplomatic conferences of the heads of government of the alliances to define their common purposes or to deal with emerging crises. This concert mechanism functioned like a precursor of the United Nations Security Council. Its conferences acted on a series of crises, attempting to distill a common course: the revolutions in Naples in 1820 and in Spain in 1820–23 (quelled by the Holy Alliance and France, respectively) and the Greek revolution and war of independence of 1821–32 (ultimately supported by Britain, France, and Russia). The Concert of Powers did not guarantee a unanimity of outlook, yet in each case a potentially explosive crisis was resolved without a major-power war.

A good example of the efficacy of the Vienna system was its reaction to the Belgian revolution of 1830, which sought to separate today’s Belgium from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. For most of the eighteenth century, armies had marched across that then-province of the Netherlands, in quest of the domination of Europe. For Britain,

whose global strategy was based on control of the oceans, the Scheldt River estuary, at the mouth of which lay the port of Antwerp across the channel from England, needed to be in the hands of a friendly country and under no circumstances of a major European state. In the event, a London conference of European powers developed a new approach, recognizing Belgian independence while declaring the new nation “neutral,” a heretofore-unknown concept in the relations of major powers, except as a unilateral declaration of intent. The new state agreed not to join military alliances or permit the stationing of foreign troops on its territory. This pledge in turn was guaranteed by the major powers, which thereby undertook the obligation to resist violations of Belgian neutrality. The internationally guaranteed status lasted for nearly a century; it was the trigger that brought England into World War I, when German troops forced a passage to France through Belgian territory.

The vitality of an international order is reflected in the balance it strikes between legitimacy and power and the relative emphasis given to each. Neither aspect is intended to arrest change; rather, in combination they seek to ensure that it occurs as a matter of evolution, not a raw contest of wills. If the balance between power and legitimacy is properly managed, actions will acquire a degree of spontaneity. Demonstrations of power will be peripheral and largely symbolic; because the configuration of forces will be generally understood, no side will feel the need to call forth its full reserves. When that balance is destroyed, restraints disappear, and the field is open to the most expansive claims and the most implacable actors; chaos follows until a new system of order is established.

That balance was the signal achievement of the Congress of Vienna. The Quadruple Alliance deterred challenges to the territorial balance, and the memory of Napoleon kept France—suffering from revolutionary exhaustion—quiescent. At the same time, a judicious

attitude toward the peace led to France’s swift reincorporation into the concert of powers originally formed to thwart its ambitions. And Austria, Prussia, and Russia, which on the principles of the balance of power should have been rivals, were in fact pursuing common policies: Austria and Russia in effect postponed their looming geopolitical conflict in the name of their shared fears of domestic upheaval. It was only after the element of legitimacy in this international order was shaken by the failed revolutions of 1848 that balance was interpreted less as an equilibrium subject to common adjustments and increasingly as a condition in which to prepare for a contest over preeminence.

As the emphasis began to shift more and more to the power element of the equation, Britain’s role as a balancer became increasingly important. The hallmarks of Britain’s balancing role were its freedom of action and its proven determination to act. Britain’s Foreign Minister (later Prime Minister) Lord Palmerston offered a classic illustration when, in 1841, he learned of a message from the Czar seeking a definitive British commitment to resist “

the contingency of an attack by France

on the liberties of Europe.” Britain, Palmerston replied, regarded “an attempt of one Nation to seize and to appropriate to itself territory which belongs to another Nation” as a threat, because “such an attempt leads to a derangement of the existing Balance of Power, and by altering the relative strength of States, may tend to create danger to other Powers.” However, Palmerston’s Cabinet could enter no formal alliance against France because “it is not usual for England to enter into engagements with reference to cases which have not actually arisen, or which are not immediately in prospect.” In other words, neither Russia nor France could count on British support as a certainty against the other; neither could write off the possibility of British armed opposition if it carried matters to the point of threatening the European equilibrium.

The subtle equilibrium of the Congress of Vienna system began to fray in the middle of the nineteenth century under the impact of three events: the rise of nationalism, the revolutions of 1848, and the Crimean War.

Under the impact of Napoleon’s conquests, multiple nationalities that had lived together for centuries began to treat their rulers as “foreign.”

The German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder

became an apostle of this trend and argued that each people, defined by language, motherland, and folk culture, had an original genius and was therefore entitled to self-government. The historian Jacques Barzun has described it another way:

Underlying the theory was fact

: the revolutionary and Napoleonic armies had redrawn the mental map of Europe. In place of the eighteenth century horizontal world of dynasties and cosmopolite upper classes, the West now consisted of vertical unities—nations, not wholly separate but unlike.

Linguistic nationalisms made traditional empires

—especially the Austro-Hungarian Empire—vulnerable to internal pressure as well as to the resentments of neighbors claiming national links with subjects of the empire.

The emergence of nationalism also subtly affected the relationship between Prussia and Austria after the creation of the “great masses” of the Congress of Vienna. The competition of the two great German powers in Central Europe for the allegiance of some thirty-five smaller states of the German Confederation was originally held in check by the need to defend Central Europe. Also, tradition generated a certain deference to the country whose ruler had been Holy Roman Emperor for half a millennium. The Assembly of the German Confederation

(the combined ambassadors to the confederation of its thirty-seven members) met in the Austrian Embassy in Frankfurt, and the Austrian ambassador acted as chairman.

At the same time, Prussia was developing its own claim to eminence. Setting out to overcome the handicaps inherent in its sparse population and extended frontiers, Prussia emerged as a major European state because of its leaders’ ability to operate on the margin of their state’s capabilities for more than a century—what Otto von Bismarck (the Prussian leader who brought this process to its culmination) called a series of “

powerful, decisive and wise regents

who carefully husbanded the military and financial resources of the state and kept them together in their own hands in order to throw them with ruthless courage into the scale of European politics as soon as a favorable opportunity presented itself.”

The Vienna settlement had reinforced Prussia’s strong social and political structure with geographic opportunity. Stretched from the Vistula to the Rhine, Prussia became the repository of Germans’ hopes for the unity of their country—for the first time in history. With the passage of decades, the relative subordination of Prussian to Austrian policy became too chafing, and Prussia began to pursue a more confrontational course.

The revolutions of 1848 were a Europe-wide conflagration affecting every major city. As a rising middle class sought to force recalcitrant governments to accept liberal reform, the old aristocratic order felt the power of accelerating nationalisms. At first, the uprisings swept all before them, stretching from Poland in the east as far west as Colombia and Brazil (an empire that had recently won its independence from Portugal, after serving as the seat of its exile government during the Napoleonic Wars). In France, history seemed to repeat itself when Napoleon’s nephew achieved power as Napoleon III, first as President on the basis of a plebiscite and then as Emperor.

The Holy Alliance had been designed to deal precisely with upheavals such as these. But the position of the rulers in Berlin and Vienna had grown too precarious—and the upheavals had been too broad and their implications too varied—to make a joint enterprise possible. Russia in its national capacity intervened against the revolution in Hungary, salvaging Austria’s rule there. For the rest, the old order proved just strong enough to overcome the revolutionary challenge. But it never regained the self-confidence of the previous period.

Finally, the Crimean War of 1853–56 broke up the unity of the conservative states—Austria, Prussia, and Russia—which had been one of the two key pillars of the Vienna international order. This combination had defended the existing institutions in revolutions; it had isolated France, the previous disturber of the peace. Now another Napoleon was probing for opportunities to assert himself in multiple directions. In the Crimean War, Napoleon saw the device to end his isolation by allying himself with Britain’s historic effort to prevent the Russian reach for Constantinople and access to the Mediterranean. The alignment indeed checked the Russian advance, but at the cost of increasingly brittle diplomacy.