You Must Change Your Life (3 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

Rodin eventually coped by turning against the pretentious academy, which he decided was filled with nepotists and guarded by elites who “hold the keys of the Heaven of Arts and close the door to all original talent!” He suspected that his exclusion had to do with his inability to supply letters of recommendation from renowned artists, which other boys had been able to obtain through family connections.

Rodin gave up on art school for good. He continued making his own work, but, denied his “heaven,” he stopped copying the idyllic Greek and Roman statues and adopted a kind of aesthetic of survival. From then on, his art was to be grounded in life, in all its unexceptional misery. He began to accentuate forms that clung desperately to their existence, and those that had been grotesquely defeated by it.

WHEN HE WAS EIGHTEEN,

it came time for Rodin to earn a proper living. So, in 1858, he took a job stirring plaster and cutting molds for building ornaments. He was a cog in an assembly line that began with an architect whose blueprints would call for flowers or caryatids or demon heads, which Rodin would then sculpt in plaster. He then gave the model to a mason to reproduce in stone or metal. Finally it went to the construction worker to affix to the side of a building.

This sculpt-by-numbers approach left Rodin feeling depressed and uninspired. Once he caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror and for a moment saw himself as his uncle, who had also been a plaster craftsman and wore a smock streaked with white paste. He was starting to believe that this job might be it for him. Perhaps he had been foolish to think he could be an artist. “When one is born a beggar, one had better get busy and pick up the beggar's pouch,” he lamented to his sister at the time.

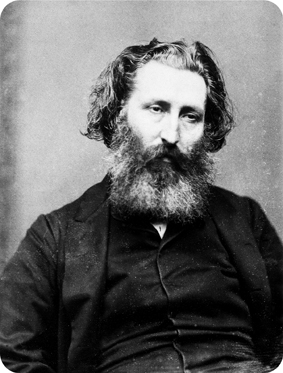

Auguste Rodin circa 1875

.

But the more Rodin eased into the routine of his job, the more a new world began to open up for him there. One day he was gathering leaves and flowers from a garden with his co-worker Constant Simon. After they brought these samples back to the studio to model in plaster, Simon observed Rodin's technique. “You don't go about that correctly,” he told his younger colleague. “You make all your leaves flatwise. Turn them, on the contrary, with the tips facing you. Execute them in

depth

and not in

relief

.” The form should push out from the

center and advance toward the viewer, he explained, otherwise it was merely an outline.

“I understood at once,” Rodin said. “That rule has remained my absolute basis.” He couldn't believe he hadn't come to this brilliantly simple logic sooner. Through the example of a leaf he had learned more than most students did in all of art school, he thought. Young people were so busy copying the sculptures of antiquity that they scarcely even noticed nature. And they were so preoccupied with emulating the latest greats in the salons that they failed to recognize the everyday mastery of craftspeople like Simon.

Perhaps the monotonous labor he endured now was what the cathedral builders felt when they laid brick upon brick to build their masterpieces, Rodin thought. He did not share their devotion to god, but he did feel a love that intense for nature. Perhaps if he could sculpt each leaf as if it were a tiny act of worship, then he could take pride in his work as a humble servant of nature. After all, no cathedral builder was singled out for his work, nor would glory come to any one building ornamenter. The cathedral was a triumph that belonged to all its artisans, and it would outlive every last one of its nameless makers.

“How I should love to sit at the table with such stone carvers,” Rodin went on to write. He would later warn young artists to beware of the “transitory intoxication” of inspiration. “Where did I learn to understand sculpture? In the woods by looking at the trees, along roads by observing the formation of clouds . . . everywhere except in schools.”

Yet Rodin still had to accomplish one crucial lesson from nature, that of the human form. Without access to live models, he settled for studying humbler versions of anatomy. He became a regular at the Dupuytren, a medical museum just down the street from the Petite Ãcole. The diseased body parts on view there undoubtedly influenced the contorted shapes of the hundreds of hands Rodin would sculpt over the years, some of which physicians have since claimed they can diagnose by sight.

Other times Rodin studied animal figures. There were markets

all over town for the buying and selling of dogs, pigs and cattle, but Rodin's favorite was the horse fair on the corner of the Boulevard de l'Hopital, in front of the Salpêtrière psychiatric facility. He watched the owners lead their horses out from stalls and trot them up and down the dirt path. Sometimes he saw the naturalist painter Rosa Bonheur there, dressed as a man to avoid attention as she worked on reproductions of her famous painting

The Horse Fair

.

He also frequented the Jardin des Plantes, a seventy-acre menagerie in southeastern Paris that was home to a botanical garden, the world's first public zoo and a natural history museum, where Rodin enrolled in a course on zoological drawing. It was held in the museum's dank basement, and an uninspiring instructor lectured Rodin's class about skeletal structure and bone composition. When it came time for critique the man shuffled between the sculptors' blocks, muttering little more than, “All right, that's very good.” The students, bored by the scientific minutiae, amused themselves by making fun of the old man's cheap suits and the way his shirt buttons fought to contain his paunch.

In a decision he would come to regret, Rodin dropped out before the end of the term. He later learned that the professor was a true master in disguise: Antoine-Louis Barye, one of the finest animal sculptors in European history. Sometimes called the “Michelangelo of the Ménagerie,” Barye had been examining the caged carnivores of the Jardin since 1825, often with his friend the painter Eugène Delacroix. When an animal died, Barye was first on the scene to dissect it and compare its measurements to those in his drawings. Once, in 1828, Delacroix notified him of a new cadaver by writing, “The lion is dead. Come at a gallop.”

Barye was a former goldsmith who defied the rigid realism of the day with wildly expressive bronzes. In his hands, a gnu being strangled by a python did not merely collapse to the ground in defeat. Instead, the beast's body merged with the serpent's coil as it sucked away its life and identity in what became a potent allegory for the dehumanization of war. Reviewing Barye's work in the 1851 Paris

Salon, the critic Edmond de Goncourt wrote that Barye's

Jaguar Devouring a Hare

marked the death of historicist sculpture and the triumph of modern art.

There was no shortage of demand for work by the great

animalier

, but Barye was a perfectionist who refused to sell anything that did not live up to his exacting standards. Thus he never earned the money to match his talent and went through life looking like a pauper.

It was not until Rodin reached middle age that he finally recognized the significance of Barye's animal studies. The epiphany came to him one afternoon while strolling down a Paris street, gazing absentmindedly into the shop windows. A pair of bronze greyhounds in one of the displays caught his eye: “They ran. They were here, they were there; not for an instant did they remain in one spot,” he said of the sculptures. When he looked closer he saw that they bore the signature of his old professor.

“An idea came to me suddenly and enlightened me; this is art, this is the revelation of the great mystery; how to express movement in something that is at rest,” Rodin said. “Barye had found the secret.”

From then on, motion became the dominant concern in Rodin's work. He began intuiting tiny gesturesâthe curve of a model's arm or a bend in the spineâand amplifying them into new, large-scale actions. His human figures took on an animal intensity; in sculpting one especially muscular model he said he imagined her as a panther. Years later the critic Gustave Geffroy identified Rodin's debt to his old master. Rodin “takes up the art of sculpture where Barye left off; from the lives of animals he proceeds to the animal life of human beings,” he wrote in in

La Justice

.

Once Rodin had discovered his taskâto express inner feelings through outward movementâhis work departed further from that of his historical heroes and began to fall into step with the flux and anxiety of the rapidly modernizing world around him.

CHAPTER

2

I

N A CHILDHOOD DREAM, THE YOUNG POET LAY ON A BED OF

dirt beside an open grave. A tombstone etched with the name “René Rilke” loomed overhead. He did not dare lift a limb for fear that the slightest movement might topple the heavy stone and knock him into the grave. The only way to escape his paralysis was to somehow change the engraving on the stone from his name to his sister's. He did not know how to do it, but he understood that freedom required rewriting his fate.

The fear of being crushed by a rock became a recurring theme in the boy's nightmares. It wasn't in every case a tombstone, but it was always something “too big, too hard, too close,” and it often portended a painful transformation; a rebirth contingent upon the downfall of that which came before him.

Indeed, it was a death that chaperoned the poet's very entrance into the world, on December 4, 1875. A young housewife from a well-to-do family, Sophia Rilke lost an infant girl a year before giving birth to her only son. From the moment he was born, she saw him as her replacement daughter and christened him with the feminine name René Maria Rilke. Sometimes she called him by her own nickname, Sophie. Born two months prematurely, the boy stayed small for his age and passed

easily for a girl. His mother outfitted him in ghostly white dresses and braided his long hair until he entered school. This splintered identity had mixed consequences for Rilke. On the one hand, he grew up believing that there was something fundamentally mistaken about his nature. But on the other, his acquiescence pleased his mother, which was something no one else seemed able to do, especially not his father.

A young Rainer Maria Rilke, dressed as a girl, circa 1880

.

Josef Rilke worked for the Austrian army as a railroad station master. He never rose to the officer's rank that his well-bred wife had hoped for, and he spent the rest of his marriage paying for the disappointment. His good looks and early professional promise initially won his bride over, but Sophia prized status above all else and never forgave Josef for failing to bring her the noble title she had bargained for.

Josef, meanwhile, resented the way she babied René, and later blamed her for the boy's incessant versifying. He was not mistaken. Sophia had decided that if they weren't going to be granted nobility, they would

fake it, and so she began teaching René poetry in an attempt to “refine” him. She had him memorizing Friedrich Schiller verses before he could read and copying entire poems by age seven. She insisted he learn French, too, but certainly not Czech. Under the imperial rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czech was relegated to the servant classes, while German became the dominant language in Prague.