You Must Change Your Life (8 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

When Rodin agreed to the commission he did not say what the statue would look like, quite possibly because he didn't have a clue himself. He still had to conduct extensive research, beginning with a trip to the author's hometown, and then locate a model with just the right physiognomy. At the same time, he was completing several other monuments to French genius, to Hugo, Baudelaire and the painter Claude Lorrain.

Delaying matters further, he and Claudel were fighting worse than ever. As Rodin's fame grew during these years, so did attention from his models and other admirers. Claudel felt that he had allowed these outsiders to encroach on their sacred privacy, and her jealousy flared up more and more. She had also begun to doubt whether he would ever fulfill his promise to leave Beuret.

Beuret was keenly aware of Rodin's affair with Claudel. Although

it tormented her, she preferred to look the other way rather than surrender him altogether. But unlike with his previous infidelities, she sensed for the first time that Claudel posed a serious threat and she knew she couldn't just stand by. The two women became bitter rivals, with Beuret once reportedly pulling a gun on the young mistress after catching her spying from the shrubs outside their house. Claudel, meanwhile, gave Rodin a series of drawings depicting Beuret as a broomstick-wielding ogress and, in another, a feral beast crouched on all fours. Rodin often appears in them, tooâshackled, shriveled and stripped nude. Rodin pretended that the situation was entirely out of his hands. He had no problem continuing separate relationships with both women, and couldn't fathom why Claudel couldn't appreciate that she was the favored one.

Eventually the resentments and failed promises became more than Claudel could bear. Her emotions had started consuming all of her energy and distracted her from work. By 1893, she felt she had lost something of herself in Rodin and initiated a separation. Rodin, devastated but unwilling to put up a fight, slunk quietly away and began looking for property outside of Paris for himself and Beuret.

Ending the relationship with Rodin proved to be only the beginning of Claudel's troubles, however. Emerging from beneath the massive shadow he had cast over her career proved far more complicated. Her reputation as his mistress was by then well known, and that made it nearly impossible to carve out a style for herself that did not remind people of his. Her strategy was to confront the rumors head-on and speak out unreservedly about the ways he had taken advantage of her vulnerability, as a much younger woman and as an aspiring artist.

Much to Claudel's horror, Rodin continued trying to promote her career. A year after their split, he visited an exhibition that included one of her busts and announced to the press that it had “hit me like a blow of the fist. It has made her my rival.” For years he went on quietly securing her jobs and exhibitions behind her back.

When Claudel found out that his influence had factored into one commission, in 1895, she turned the work into a withering rebuttal. She spent four years crafting the three life-sized bronze figures into an elaborate revenge fantasy: A winged hag drags a feeble old man, one of his arms hanging back in the direction of a nude woman, who has fallen to her knees. The girl reaches out for the man, imploring him to come back. But it is too late, the she-beast has him in her claws for good.

When the work, titled

The Age of Maturity

, debuted in 1902, already tense relations with Claudel's family worsened. Her mother and sister blamed her for tarnishing the family name. Her brother, the Christian poet Paul Claudel, described his horror at seeing the sculpture for the first time: “This young nude girl is my sister! My sister Camille, imploring, humiliated, on her knees; this superb, this proud young woman has depicted herself in this fashion.”

Claudel locked herself up in her studio for nearly twenty years. Worried she'd forget how to speak, she took to talking to herself. Rodin's covert machinations on her behalf fueled a paranoid belief that he was following her and stealing her ideas. She lived in filth and impoverishment until, in 1913, her brother committed her to a mental institution. He was convinced that the demon from

The Age of Maturity

had ripped more than Rodin from her. It had torn away “her soul, genius, sanity, beauty, life, all at the same time.”

Others were not so sure of her insanity, however. Several friends who visited Claudel reported back that she seemed in full possession of her wits and wanted nothing more than to return home. A number of letters she wrote at the time suggest the same. “I am so heartbroken that I have to keep living here that I am no longer human,” she wrote to her mother in 1927. She could not understand why she was the one being punished when it was Rodin, an old “millionaire,” who had exploited her. Yet her pleas went unanswered and she remained at the asylum for thirty years, until she died at age seventy-nine. She was buried there in a mass grave.

Perhaps even more tragic, however, is the reality that Claudel succumbed

to her greatest fear, that her name would be eternally entwined with Rodin's. During her lifetime alone, the affair became popular tabloid gossip and fodder for dramatic works like Henrik Ibsen's 1899 play

When We Dead Awaken

. After Claudel's death, her brother donated many of her works to the Musée Rodin, which today houses the largest collection of Claudel's sculptures in the world.

CHAPTER

4

I

N THE TWENTY-FIVE YEARS LEADING UP TO THE TURN OF

the century, the population of most major European cities doubled, if not tripled. Writers took to describing the rapid urbanization in terms of disease. The smog-engulfed metropolis became a festering sore, oozing sewage into the rivers, sulfurizing the air and breeding bacteria as residents piled on top of each other in apartment complexes.

A fear of contagions bred citywide panic, and soon panic itself became a disease. As medical schools began to introduce a condition known as hysteria, thought to be caused by the uterus, more than five thousand mentally ill, epileptic, poor or otherwise incurable women in Paris were banished to the Salpêtrière, a former gunpowder factory turned hospital next door to the Jardin des Plantes.

Some would have called it a death factory. “Behind those walls, a particular population lives, swarms, and drags itself around: old people, poor women,

reposantes

awaiting death on a bench, lunatics howling their fury or weeping their sorrow in the insanity ward or the solitude of the cells . . . It is the Versailles of pain,” wrote the journalist Jules Claretie. Patients slept three or four to a bed. Its own director called it “the great emporium of misery.”

Presiding over this hell was Jean-Martin Charcot, the founding

father of neurology, who earned the nickname “Napoleon of Neuroses.” He transformed the Salpêtrière from a “wilderness of paralyses, spasms and convulsions” into a leading teaching and research hospital. Charcot was a brilliant scientist, but he bellowed from the pulpit of his morning lectures like a snake-oil salesman. Crowds lined up early to see him conduct live hypnotisms and tame hysterical women onstage.

In 1885, Charcot's lectures attracted a young neurologist from Vienna, Sigmund Freud. “Charcot was perfectly fascinating: each of his lectures was a little masterpiece in construction and composition, perfect in style, and so impressive that the words spoken echoed in one's ears, and the subject demonstrated remained before one's eyes for the rest of the day,” he said. Freud's studies with Charcot derailed him from his research-based track and he returned to Vienna ready to embark on a clinical path. He spread Charcot's theories on hysteria to his colleagues and would soon incorporate them into his own invention, psychoanalysis.

Freud described Charcot as a

visuel

, “a man who sees.” Because Charcot had been unable to pinpoint a neurological basis of hysteria, he focused instead on its symptomsâon the way it

looked

. He diagnosed by intuition. An amateur artist, Charcot drew illustrations of some of hysteria's most common manifestations: contorted facial expressions, convulsive tics, strained postures. Charcot accumulated so many casts and illustrations of tormented bodies during his career that he eventually opened the Charcot Museum, one of several anatomical museums that were launched in response to the growing fascination with disease and decay in those days. The institutional context lent a scientific authority to a process of observation and representation that might otherwise have been considered purely artistic.

Seeking to bridge this gap between art and science, Charcot wrote a book diagnosing characters in historical paintings and, by extension, the artists themselves. His disciple Max Nordau went on to become a best-selling author with a book that similarly medicalized degenerate art. He claimed that the Impressionists were hysterics with dull vision and stunted color perception, which explained why Puvis de

Chavannes painted in “whitewash” and Paul-Albert Besnard used “screaming” primary colors.

Gradually, hysteria shifted from a purely clinical condition to a cultural one. Zola wrote twenty novels about the nervous decline of a family in his Rougon-Macquart series. Rodin's vision of Dante's hell in the

Gates

mirrored the realities of life in Paris at the

fin de siècle

. The twisted figures pantomimed Charcot's illustrations of agonized ambivalence and neuroses. In Rodin's inferno, the inhabitants were everymen living in a nightmare of their own earthly passions. Love was war, desire undid reason. To him, hell had nothing to do with justice; punishment was the condition of the living.

ALL THROUGHOUT HIS

drawn-out heartbreak with Camille Claudel, Rodin was meant to be working on the monument to Balzac. He had promised to deliver it within eighteen months, but it ultimately took him seven years. He had started with a series of naturalist studies of Balzac, but threw them all out when he decided that the man's physical appearance did not adequately express his genius. It was the same false start he had made with

The Thinker

, in which he had attempted to portray the writer, Dante, rather than the mind behind it.

In another version, Rodin tried to convey the essential nature of Balzac's creativity with a nude version of the man gripping himself at the source of masculine “creation,” but nudity seemed too disrespectful. Still another pose looked too academic. The neck was too weak at first, then too strong. At last Rodin concluded that draping Balzac in his dressing gown was the only truthful way to depict him.

“Does an inspired writer dress otherwise when at night he walks feverishly in his apartment in pursuit of his private vision?” Rodin explained to one of his biographers. “I had to show a Balzac in his study, breathless, hair in disorder, eyes lost in dream . . . there is nothing more beautiful than the absolute truth of real existence.”

Rodin's statue was once again

too

truthful, however, for many of those who attended its debut at the 1898 Salon de la Société Nationale.

The

Balzac

was billed as one of the event's top attractions and lured many of the author's fans who might not otherwise have visited the art show. But to their horror, they found not their beloved

litt

é

rateur

posing obediently with a book in hand, but a colossal monsterâwith something very different in his hand. Rodin's Balzac had meaty lips, sagging jowls and a belly that bulged out from under a shapeless bathrobe. Critics were gleefully appalled: Was it a melting snowman? A slab of beef? A penguin? A lump of coal? they asked. Why was he wearing a hospital gown? And was he fondling himself under that robe?

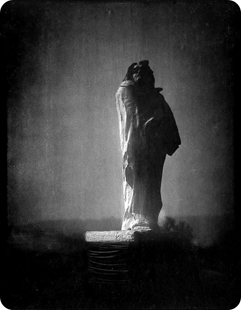

Rodin's

Monument to Balzac,

as photographed by Edward Steichen in 1908

.

It was too much even for those who wanted to give Rodin the benefit of the doubt. “Help me find something beautiful in these goiters, these growths, these hysterical distortions!” wrote one critic of his attempt to see what Rodin's followers saw. Alas, “I did not, and I've covered my forehead with ashes. I shall never belong to the Religion.”