Young Woman and the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World (24 page)

Authors: Glenn Stout

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Sports, #Swimming, #Trudy Ederle

Trudy meeting the press before leaving for Europe for her successful attempt.

(Library of Congress)

Aileen Riggin (left) and Helen Wainwright (right) see Trudy off aboard the

Berengaria

as she returns to Europe to make her second attempt to swim the

Channel.

(Library of Congress)

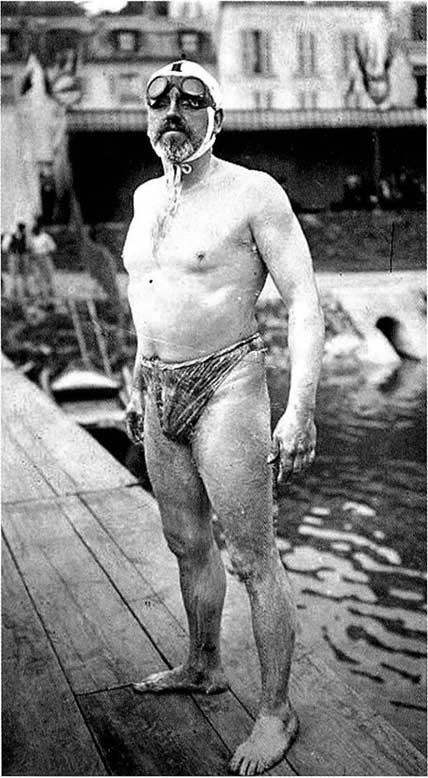

Thomas William "Bill" Burgess, the second man to swim the Channel, 1909.

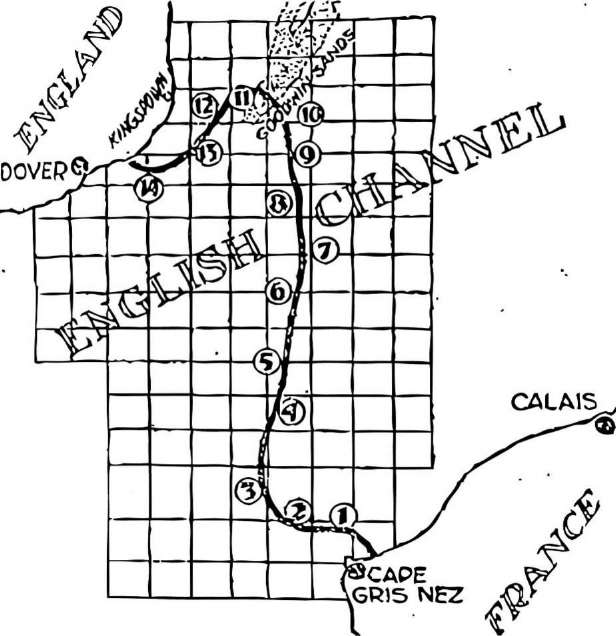

This map was prepared before Trudy's crossing and shows what Bill Burgess hoped would be her hourly progress on her route across the English Channel. Incredibly, and despite poor weather, Trudy Ederle managed to stay close to this course until the final hours, when tidal currents forced her to the northeast before she finally struck out for the beach at Kingsdown.

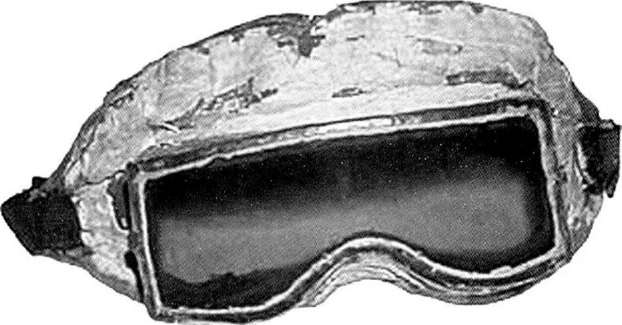

Trudy's famous goggles, now a part of the collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

Trainer Bill Burgess coats Trudy with grease before her successful crossing of the Channel. (

New York Historical Society)

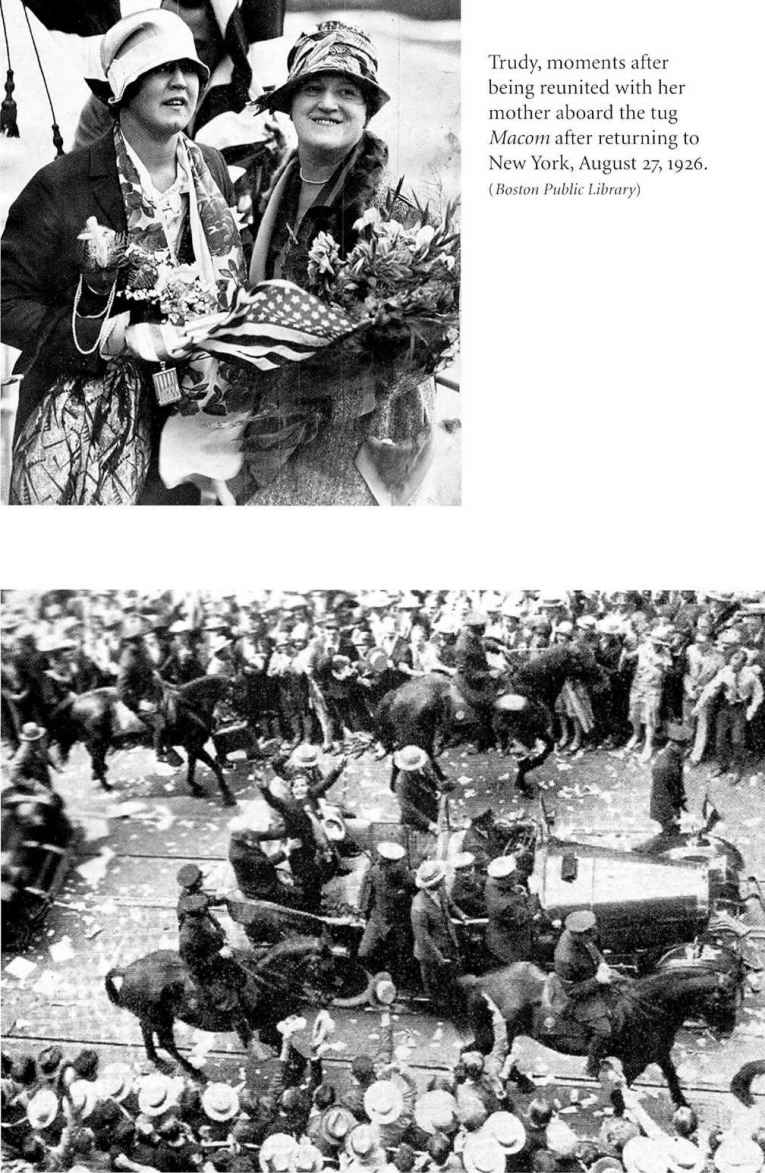

Trudy, moments after being reunited with her mother aboard the tug

Macom

after returning to New York, August 27, 1926.

(Boston Public Library

Crowds surround Trudy during the ticker-tape parade following her return to the United States after conquering the English Channel.

Trudy is lost in the crowd and ticker tape as New York celebrates her achievement.

(Library of Congress)

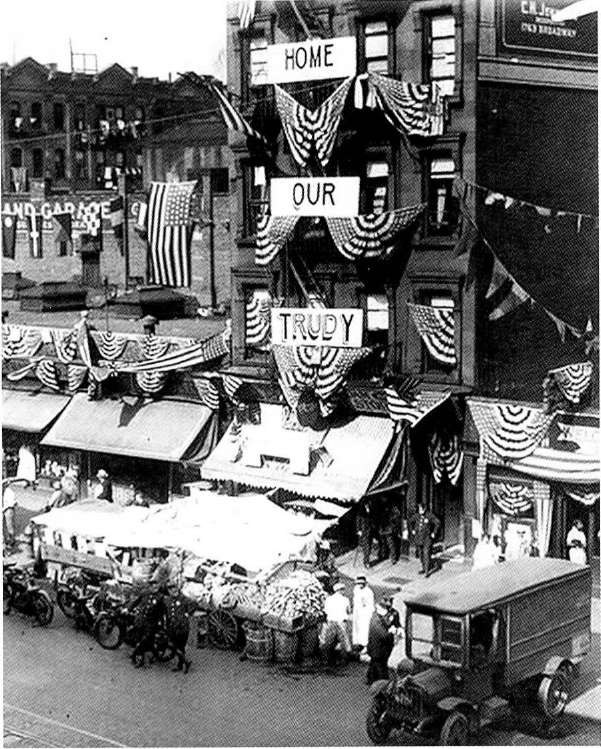

Trudy's house on Amsterdam Avenue, decorated to welcome her home a few days after her return from her triumphant swim. Police still guard the door to the street.

American team were expected to cost about $350, 000, but the committee had less than $250, 000 in hand and was already $53, 000 in debt to its president, Robert Thompson, who reportedly had paid housing expenses in Paris in advance out of his own pocket. Already the committee was cutting back on the number of athletes it was sending to the games—slashing the fencing team from eighteen to fourteen men, the boxing squad from twenty-five to sixteen, and choosing to create a water polo team from among the men's swim team rather than send a separate squad—and there were rumors of more cuts to come. Since women's swimming was a relatively new event, and some members of the AOC still viewed female athletes with disdain, there was a real chance the team might be cut to the bone. Even a second-place finish at the trial might not secure passage to Paris.

That wasn't the only concern. Some competitors showed up for the trials with a checkbook, from their own family or club, or in the name of a well-heeled patron. Large donations to the AOC often came attached to very strong string—they were dependent on whether certain entrants made the team, and Olympics officials were far from immune to such pressure. In the past, lesser athletes had been selected for the Olympic team almost entirely due to the amount of money their selection promised to deliver. It often explained the selection of alternates, many of whom held a purse string. This allowed the AOC to take the money and still retain some integrity.

For Trudy, the bar was even a little bit higher. She was not only expected to win her trials, but to drum up publicity and raise funds. During the trials, Olympics officials decided to hold a special 150-meter race between Trudy and Helen Wainwright, despite the fact there wasn't even Olympic competition at that distance. It would be the first time that event had ever been held in the United States, where apart from the Olympic trials, most races were measured by yards rather than the international standard of meters.

As if her task wasn't hard enough already, the special race made it a bit more difficult, but Trudy didn't really mind. Over the past two years she had slowly grown into her role as the face of the WSA, and as she grew and matured she was beginning to come out of her shell a bit, although she disliked being left alone around strangers without her sister, her coaches, or her friends to act as a buffer. But the young girl who had dashed out of the surf after winning the Day Cup was now a young woman who realized her responsibilities to others and was ever more cautious about the kind of impression she left. She had grown accustomed to being in the public eye and watched what she said and did, but around the other WSA girls Trudy never put on any airs and behaved as if she were just another novice. Still, Trudy would have to swim to win a place on the Olympic team. There would be no coasting, and for the first time in her life she would be competing under real pressure.

Fortunately, she had an advocate in Coach Handley, and he did what he could to make things easier for her. He had the latitude to select the members of the 400-meter relay team himself, in team trials to be held in Paris, and he saw no need for Trudy to overtax herself at the trials at Briarcliff. After all, if the unexpected happened—an injury, illness, cramps, and the like—and Trudy lost, she risked not qualifying at all. That would be a disaster, for there was already talk that she should win three gold medals at the Olympics—not could win, but

should

win. Although the 400-meter individual race was scheduled for the first day of the trials, both the 100-meter race and special 150-meter race were scheduled for day two, a tough schedule. But Handley had an idea.

He had Trudy skip the 100-meter trials entirely. There was still time for her to earn her spot in the 100-meter swim at more team trials in Paris, and if she held back now, that would open up room on the team for several alternates. He could always name Trudy to the 100-meter squad after the team arrived in France, keeping everyone relatively happy.

As expected, on the first day of the trials, in the rain, Trudy won the 400-meter race handily, with Helen Wainwright finishing a distant second. Like Trudy, Handley also held Wainwright out of the 100-meter race on day two as well. Now both girls could focus on the 150-meter race.

The rivalry between the two girls, while outwardly pleasant, was intense. If not for Trudy, Helen Wainwright would have been considered the greatest swimmer in world. And Wainwright, from Corona in Queens, was all that stood between Trudy and perfection—Ederle's only defeat in the last year and half had been against Wainwright, in a 50-yard sprint, and she was the only swimmer in the world to regularly challenge her. Neither girl treated the 150-meter contest like an exhibition.