Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (9 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Psychological mindfulness involves the nonjudgmental acceptance of thoughts, feelings, and body sensations. It specifically does not involve analysis of what one is thinking or feeling, and research is increasingly showing that this state of “mind” is a powerful state that can significantly reduce anxiety and worry.

42

–

44

As we learned earlier, reducing worry can help thinking and productivity. Thus, awareness of the worry without judgment can help thinking considerably. Mindfulness as a practice can also decrease negative thoughts that intrude upon a leader’s mind.

45

Brain science can help elucidate what is going on in the brain during mindfulness. Extensive research has shown that mindfulness leads to a better quality of life through feeling better and having less

emotional distress. In addition, mindfulness practice can influence the brain, the autonomic nervous system, stress hormones, the immune system, and health behaviors.

46

Mindfulness is more accurately regarded as emotion-introspection rather than cognitive self-reflection. Rather than “thinking” about the self, mindfulness results in people being aware of themselves without thinking. This has been shown to decrease amygdala activation, whereas self-reflection actually increases amygdala activation compared to doing something neutral.

47

Thus, this technique can be especially helpful when leaders are stressed or anxious.

A recent article pointed out that the human brain is spatially organized in a finite set of specific coherent patterns, namely resting state networks (RSNs).

48

These networks include default-mode, dorsal attention, core, central-executive, self-referential, somatosensory, visual, and auditory networks. The self-referential network relates to mindfulness and its role in self-awareness. This study showed that this RSN exerted the greatest control over other RSNs and is one of the highest-order influences over the rest of the brain. Thus, the network of brain cells that represents mindfulness in the brain determines most powerfully how we see, think, hear, and attend. Therefore, leaders should understand the power of the mindfulness circuit in the human brain.

Mindfulness reflects a steadiness in attention, but within this steadiness are different levels as well. For example, focused attention (when attention is focused on a task or object), open monitoring (where attention is kept in the monitoring process), and automatic self-transcending (not-yet-embodied knowledge) have all been shown to correlate with different brainwave patterns.

49

Focused attention correlates with beta-gamma activity (12–100 Hz), open monitoring correlates with theta activity (4–7 Hz), and automatic self-transcending with alpha 1 activity (8–10 Hz). An article in the

Journal of Knowledge Management

has emphasized that “in order to successfully compete for increasing return markets, leaders need a

new type of knowledge that allows them to sense, tune into and actualize emerging business opportunities—that is, to tap into the sources of not-yet-embodied knowledge.”

50

These different states of consciousness interact with each other.

51

The application:

In certain situations, decreasing stress and increasing focus may require mindfulness, which is an important but difficult-to-describe process. Brain science can help us do this. Although the process of mindfulness involves a certain stillness as the strategy, the results can often be quite concrete.

For example, Wong and colleagues described how Yantian International Container Terminals Limited (YICT) used organizational mindfulness perspectives (preoccupation with failure and success, reluctance to simplify interpretations, sensitivity to operations, commitment to resilience, and reliance on expertise over formal authority) to deal with institutional pressures faced by YICT in its IT management (ITM).

52

They also described how YICT coped with its institutional pressures during its IT development using mindfulness to generate very specific outcomes.

Essentially, mindfulness is a form of self-understanding that does not involve thinking but instead involves self-awareness. This ability to be “still” and to practice just “being” with one’s body and mind without active intervention has been shown to be critical to effective decision making. In fact, the brain circuit that activates when a leader is mindful is probably the most influential circuit affecting information processing. Without this mindfulness, the amygdala overactivates. However, brain imaging studies have shown that with mindfulness, the amygdala is quieted down and the leader will have better access to thinking circuits in the brain.

The importance of self-transcending can be emphasized as gaining access to not-yet-embodied knowledge. That is, coaches, leaders, and managers can know that self-transcending is a distinct brainwave state different from focused attention or stillness. The advantage of this is that the leader may be able to make predictions of future events more

quickly or intuitively.

53

The theory behind this thinking is to take the brain to the highest level of synchrony and connection among its various parts.

54

The Psychology of Compassion

The concept:

Leaders are often faced with a decision about whether or not to be compassionate, and coaches who prescribe compassion in certain situations are left with very “soft” ideas that cannot be adequately communicated. Although compassion always seems like a noteworthy virtue, its actual effect on the leader’s brain can help him or her understand the need for it. A recent brain-imaging study looked at experienced and novice meditators to see if their brains registered emotional sounds differently during compassion meditation (i.e., while cultivating compassion).

55

This study found that emotional sounds of distress activated the insula and cingulate cortex during meditation but not rest. Activation to negative sounds during meditation was greater in the insula of expert meditators compared to novice meditators, but this was not true for positive or neutral sounds. Thus, high degrees of compassion result in a much higher degree of emotion sharing. In addition, other brain regions (amygdala and “mirror neuron” regions; see

Chapter 3

) also activated more in experienced meditators. This suggests that mindfulness through compassion meditation results in higher emotional and social intelligence in leaders and that this depth of information provides more input for decision making.

Compassion does not just apply to feelings toward others. Its also applies to feelings toward one’s self. Leaders are often very self-critical and this can lead to a decrement in performance. A recent study that looked at self-criticism versus self-assurance found that self-criticism was associated with activity in lateral prefrontal cortex regions and dorsal ACC, thus linking self-critical thinking to error processing and resolution, and also behavioral inhibition. Self-reassurance was associated with left temporal pole and insula activation, suggesting that efforts to be self-reassuring engage similar regions to expressing compassion and empathy toward others.

56

Studies have also shown that people who are less sensitive to their own feelings are also less sensitive to the feelings of others.

57

The application:

Leaders who develop compassion as a principle will be able to register distress in the company more easily and sense this more easily, and perhaps earlier as well. This will allow them to act earlier in the course of events. Hence, compassion is not just a nice idea—it affects the brain’s sensitivity to emotional information. Also, it is important to be reminded of compassion toward ourselves. Without this, we will not be able to have compassion toward others and our brains will constantly be in error-monitoring mode using up vital energy that can be used for problem solving. Compassion is therefore not just a positive state of mind toward people; it is a state of mind that allows leaders to read what is going on around them more effectively so that they can preempt situations that arise more effectively and efficiently. Very often leaders are left to their own devices in their offices, designating “compassion workers” to make sure that the company is running well. However, for the leader to make effective decisions, factual and emotional information needs to be taken in. A state of compassion can facilitate this registration and integration. It is important that this does not imply that leaders should be self-critical when they feel angry or hostile. This just worsens the situation. The mentality of compassion involves acceptance of human traits with the additional skill of being able to take a step back when thinking resources are needed. Leaders, once they are on a rant, sometimes feel guilty if they do not justify or pursue that rant. On occasion, this can be a waste of mental resources. The mentality of compassion (together with mindfulness) allows leaders to take a step back.

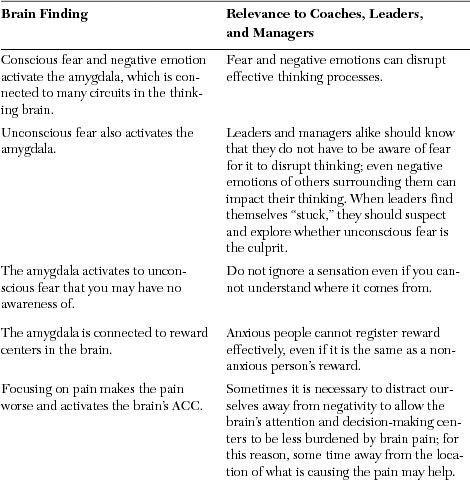

Table 2.1

provides a comprehensive summary of the concepts discussed in this chapter.

Table 2.1. Summary of Positive Psychology Concepts and Relevance to Coaches Working with Managers and Leaders

Conclusion

Positive thinking and feeling prepare the brain for better insights and thinking in the business environment. They allow for the brain to generate plans, and for seemingly impossible things to be examined in greater detail to see if we can make them possible. Think of positivity as a brain state that empowers the brain to get to solutions faster and with greater overall efficiency. Sometimes leaders may need to delegate to be mindful. They can then create the visions and distract themselves less with problem focus and engage instead in problem solving.

References

1. Seligman, M.E.P., A.C. Parks, and T. Steen, “A Balanced Psychology and a Full Life.”

Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences

, 2004. 359(1449): p. 1379–1381.

2. Giacalone, R.A., K. Paul, and C.L. Jurkiewicz, “A Preliminary Investigation into the Role of Positive Psychology in Consumer Sensitivity to Corporate Social Performance.” Journal of Business Ethics, 2005. 58(4): p. 295–305.

3. Staw, B.M., R.I. Sutton, and L.H. Pelled, “Employee Positive Emotion and Favorable Outcomes at the Workplace.”

Organization Science

, 1994. 5(1): p. 51–71.

4. Daniel, R. and S. Pollmann, “Comparing the neural basis of monetary reward and cognitive feedback during information-integration category learning.”

J Neurosci

. 30(1): p. 47–55.

5. Kahnt, T., et al., “Dorsal striatal-midbrain connectivity in humans predicts how reinforcements are used to guide decisions.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2009. 21(7): p. 1332–45.

6. Joormann, J., B.A. Teachman, and I.H. Gotlib, “Sadder and less accurate? False memory for negative material in depression.”

J Abnorm Psychol

, 2009. 118(2): p. 412–7.

7. Bauml, K.H. and C. Kuhbandner, “Positive moods can eliminate intentional forgetting.”

Psychon Bull Rev

, 2009. 16(1): p. 93–8.

8. Farson, R. and R. Keyes, “The failure-tolerant leader.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2002. 80(8): p. 64–71, 148.

9. Whalen, P.J., et al., “A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fear versus anger.”

Emotion

, 2001. 1(1): p. 70–83.