100 Most Infamous Criminals (29 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain

Blakely was a racing driver, a sophisticated, debonair man, but he soon became obsessed with Ruth. He offered to marry her, but she refused, and while she played him along, she also took up with one of his friends. For a year or so she managed to keep both men happy. But by 1954 Blakely had become almost insanely jealous. He started to beat her. He gave her a black eye; he broke her ankle; he also started seeing other women. But when Ruth finally threw him out as a result, he came back like a whipped dog, once more begging her to marry him. Again Ruth refused, but by now, it seemed, they were doomed to each other.

They set up house together in Egerton Gardens in Kensington. But by now Blakely had a taste for infidelity. At the beginning of April 1955, Ruth Ellis had a miscarriage; a few days later Blakely said he had to go and see a mechanic who was building him a new car. She followed him to an apartment in Hampstead, and when she heard a woman’s laughter inside, she knocked on the door and demanded to see him. He refused, and when she began to shout, the police were called.

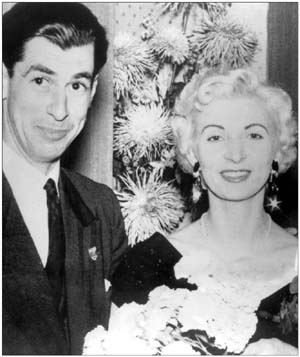

Ellis with Blakely in happier times

The next day she returned. This time she saw Blakely coming down the steps arm-in-arm with a pretty young girl. She made up her mind. On the evening of April 10th, Easter Sunday, when she found him coming out of a Hampstead pub called the Magdala, she took a gun out of her handbag and shot him six times. She later told the police:

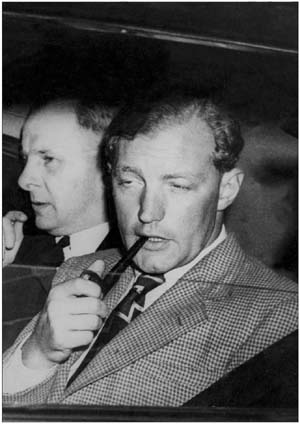

It took the jury just 14 minutes to find Ellis guilty of murder

‘I am guilty,’

and added,

‘I am rather confused.’

At her trial in June of the same year, she confessed:

‘I intended to kill him.’

It took the jury just fourteen minutes to find her guilty. She was sentenced to death, and a month later, despite widespread protests, she was hanged. Her son, the child of the American pilot, committed suicide in 1982, following years of depression. Her daughter, in a newspaper interview a year later, said she couldn’t get out of her mind the image of the hangman,

‘peering through the peephole into her cell, trying to work out how much rope he should use to make sure that frail little neck was broken.’

John Haigh

I

n 1949, when he came to trial, John Haigh was headlined in the British press as the Vampire Killer. But the only evidence that he ever drank his victims’ blood was his own – part of a ploy to have himself declared insane. In fact, he killed for money.

In 1944, as the Second World War was drawing to an end, Haigh, 34, was an independent craftsman, working part-time in a London pinball arcade owned by a man called Donald McSwann. It was McSwann who was his first victim. On some pretext, Haigh lured him down to the basement-workshop in the house he rented, and there beat him to death with a hammer. Then he dissolved his body in a vat of sulphuric acid, and poured what remained, grisly bucket by bucket, into the sewage system.

Nobody seemed to pay any attention to McSwann’s disappearance. Haigh, who took over the pinball arcade, told his parents that their son had gone to ground in Scotland to avoid the draft; he himself went to Scotland every week to post a letter to them purporting to be from him. This worked so well that in July 1945 he sent them a further letter, asking them to visit ‘his’ dear friend, John Haigh, at his home. They did. They went downstairs to inspect the basement workshop – and followed their son into the sewers.

Haigh, with the help of forged documents, made himself the McSwanns’ heir, the master of five houses and a great deal of money. But he was a gambler and a bad investor and within three years he was once more broke. So he searched out a new inheritance. He invited a young doctor and his wife to look at a new workshop he’d set up in Crawley in Surrey. They agreed…

By the time a year had passed, though, the pattern had repeated itself. Once again unable to pay his bills at the London residential hotel he by now lived in, he badly needed a fresh victim – and this was when he made his first mistake. For he chose someone much too close to him: a fellow-resident of the hotel, a rich elderly widow called Olive Durand-Deacon. Mrs. Durand-Deacon, who ate her meals at the table next to him, was under the impression that Haigh was an expert in patenting inventions and she had an idea, she said, for false plastic fingernails. He charmingly invited her to his Crawley ‘factory’ to go over the details.

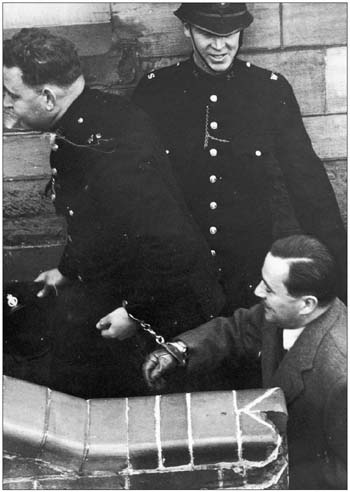

John Haigh is led to court

Haigh was dubbed the Vampire Killer by the British press

It took several days for the acid-bath to do its work on Mrs. Durand-Deacon, and in the meantime Haigh had to go to the police, with another resident, to declare her missing. The police, from the beginning, were suspicious of him and, looking into his record, they found that he’d been imprisoned three times for fraud. So they searched the Crawley ‘factory’ and though they didn’t find Mrs. Durand-Deacon, by now reduced to a pile of sludge outside in the yard, they did find a revolver and a receipt for her coat from a cleaner’s in a nearby town. They later discovered her jewellery, which Haigh had sold to a shop a few miles away.

When arrested and charged, Haigh blithely confessed, believing that, in the absence of his victim’s body, he could never be found guilty. But when a police search team painstakingly went through the sludge, they found part of a foot, what was left of a handbag and a well-preserved set of false teeth, which Mrs. Durand-Deacon’s dentist soon identified as hers.

In the end, Haigh pleaded insanity. But after a trial that lasted only two days, the jury took fifteen minutes to decide that he was both sane and guilty. The judge sentenced him to death. Asked if he had anything to say, Haigh said: ‘Nothing at all.’ He was hanged at Wandsworth prison on August 6th 1949.

Neville Heath

I

n 1946, in post-war London, Neville Heath looked just like the man he claimed to be: a dashing ex-Royal-Air-Force officer, a war hero. He had fair hair and blue eyes, an air of romantic recklessness and, like a man who has successfully cheated death, he loved to party. To women hungry for men he must have seemed made to measure: an embodiment of the gallantry that had led to victory – and of the newly carefree spirit of the times.

This nightclub Lothario, though, was not at all what he looked like. For not only was he a gigolo with a criminal record, but he also had the distinction of having been court-martialled by three separate services: by the British Air Force in 1937, the British Army in 1941, and the South African Air Force in 1945. His offences – for being absent without leave, stealing a car, issuing worthless cheques, indiscipline and wearing medals to which he wasn’t entitled and the like – all pointed in one direction: Neville Heath was a con man and poseur. He used women for money after he’d got them into his bed – as he could all too easily. But he preferred – when that palled – to beat them.

In March 1945, after guests at a London hotel reported hearing screams, a house detective burst into a bedroom to find Heath brutally whipping a girl, naked and bound hand and foot, beneath him. Neither the hotel nor the girl wanted publicity, and within two months Heath was at it again – though this time with a more willing participant, a 32-year-old occasional film extra called Margery Gardner, known in London clubs as Ocelot Margie. In May, security in another hotel intervened late at night as she lay under Heath’s lash.

Ocelot Margie, though, had no complaints to make. For she was a masochist, haunting the clubs in search of bondage and domination by any man she could find willing. She obviously found Heath to her taste. For a month later she arranged to meet him at a club, and then returned with him to the same hotel for a further session. She wasn’t to make it out alive.

In the early afternoon of the follow day, a chambermaid found her naked dead body. She had been tied at the ankles and murderously whipped, and she had extensive bruising on her face and chin, as if someone had used extreme violence to keep her mouth shut. Her nipples had been almost bitten off, and something unnaturally large had been shoved into her vagina and then rotated, causing extensive bleeding.

The police quickly issued Heath’s name and description to the press. But by this time he was in the south-coast resort town of Worthing, meeting the parents of a young woman he had earlier seduced after a promise of marriage. He quickly told her – and later her parents – his version of the murder: that he had lent his hotel room to Gardner to use for a tryst with another man and had later found her dead. He sent a letter to the police in London to the same effect, adding that he would later send on to them the murder weapon he’d found on the scene. Then he disappeared.