100 Most Infamous Criminals (30 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

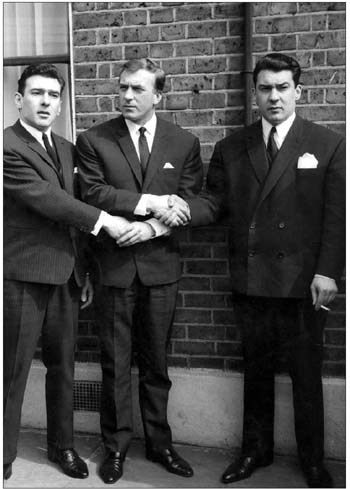

Heath’s crimes caught up with him and he was hanged in October 1946

There was huge public interest in the trial of Neville Heath

The murder weapon, of course, never arrived. But the police still failed to issue a photograph of Heath, and so he was free on the south coast for another thirteen days, posing, rather unimaginatively, as Group Captain Rupert Brooke – the name of a famously handsome poet who died in the First World War. During that time, a young woman holidaymaker vanished after having been seen having dinner with ‘Brooke’ at his hotel; and it was suggested that the ‘Group Captain’ should contact the police with his evidence. He finally did so, but was recognized and held for questioning. In the pocket of a jacket at his hotel police later found a left-luggage ticket for a suitcase, which contained, among other things, clothes labelled with the name ‘Heath,’ a woman’s scarf and a blood-stained riding-crop.

On the evening of the day Heath was returned to London and charged, the naked body of his second victim was found in a wooded valley not far from his hotel. Her cut hands had been tied together; her throat had been slashed; and after death her body had been mutilated with a knife before being hidden in bushes. Heath, though, was never tried for this murder. He came to the Old Bailey on September 24th 1946 charged only with the murder of Margery Gardner – and he was quickly found guilty by the jury. He was hanged at London’s Pentonville Prison the following month.

Jack the Ripper

N

ow that London’s famous fogs have disappeared – and with them the gas-lamps, the brick shacks, the crammed slums, the narrow streets and blind alleyways of the city’s East End – it’s hard to imagine the hysteria and terror that swept through the area when The Whitechapel Murderer – later known as Jack the Ripper – went to work. Already in 1888 two prostitutes had been murdered. So when the body of another was found, her throat cut and her stomach horribly mutilated, on August 31st, she was immediately assumed to be the brutal killer’s third victim. And brutal he was:

‘Only a madman could have done this,’

said a detective; the police surgeon agreed.

‘I have never seen so horrible a case,’

he announced.

‘She was ripped about in a manner that only a person skilled in the use of a knife could have achieved.’

A week later, the body of ‘Dark Annie’ Chapman was found not far away, this time disembowelled and with its uterus removed; and a fortnight after that, a letter was received by the Central News Agency in London which finally gave the killer a name. It read (in part):

‘Grand job, that last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear from me, with my funny little game… Next time I shall clip the ears off and send them to the police just for jolly.’

It was signed:

‘Jack the Ripper.’

Five days later, he struck again – twice. The first victim was ‘Long Liz’ Stride, whose body, its throat cut, was discovered on the night of September 30th by the secretary of a Jewish Working Men’s Club whose arrival in a pony trap seems to have disturbed the Ripper. For apart from a nick on one ear, the still-warm corpse was unmutilated. Unsatisfied, the Ripper went on to find another to kill. Just forty-five minutes later – and fifteen minutes’ walk away – the body of Catherine Eddowes, a prostitute in her 40s, was found. Hers was the most mutilated so far. For her entrails had been pulled out through a large gash running from her breastbone to her abdomen; part of one of her kidneys had been removed and her ears had been cut off. A trail of blood led to a ripped fragment of her apron, above which had been written in chalk:

‘The Juwes are The men That Will not be Blamed for nothing.’

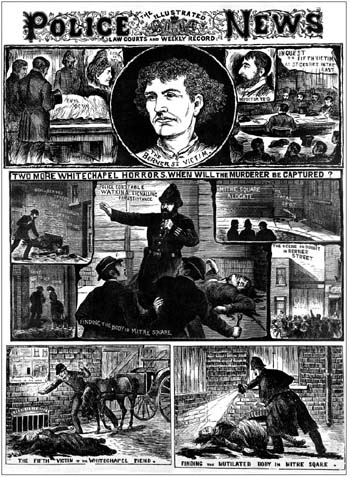

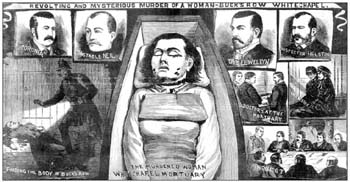

The crimes of the Ripper were luridly reported in the national press

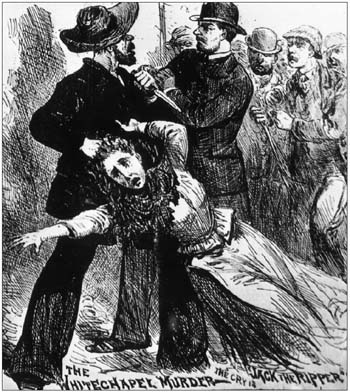

The Whitechapel Murders appalled the public

By this time 600 police and plain-clothes detectives had been deployed in the area, alongside amateur vigilantes, and rumours were rife. The Ripper was a foreign seaman, a Jewish butcher, someone who habitually carried a black bag; and there were attacks on anyone who fitted this description. He could even be – for how else could he so successfully avoid apprehension? – a policeman run mad. There was plenty of time now for speculation. For the Ripper didn’t move again for more than a month – and when he did, it was the worst murder of all. His victim was twenty-five-year-old Mary Jane Kelly; and her body, when it was found in the wretched hovel she rented, was unrecognizable: there was blood and pieces of flesh all over the floor. The man who found her later said:

An artist charts the people and events of the Ripper’s crimes

‘I shall be haunted by [the sight of it] for the rest of my life.’

This time, though, there was a clue. For Mary Jane had last been seen in the company of a well-dressed man, slim and wearing a moustache. This fitted in with other possible sightings and could be added to the only other evidence the police now had: that the killer was left-handed, probably young – and he might be a doctor for he showed knowledge of human dissection.

After this last murder, though, the trail went completely cold. For the Ripper never killed again. The inquest on Mary Jane Kelly was summarily closed and investigations were called off, suggesting to some that Scotland Yard had come into possession of some very special information, never disclosed. This has left the problem of the Ripper’s identity wide open to every sort of speculation. The finger has been variously pointed – among many others – at a homicidal Russian doctor, a woman-hating Polish tradesman, the painter Walter Sickert, the Queen’s surgeon and even her grandson, Prince Albert, the Duke of Clarence. The theory in this last case is that Albert had an illegitimate child by a Roman Catholic shopgirl who was also an artist’s model. Mary Jane Kelly had acted as midwife at the birth, and she and all the friends she’d gossiped to were forcibly silenced, on the direct orders of the Prime Minister of the day, Lord Salisbury.

The probable truth is that the Ripper was a man called Montagu John Druitt, a failed barrister who had both medical connections and a history of insanity in his family. He’d become a teacher, and had subsequently disappeared from his school in Blackheath. A few weeks after the death of Mary Jane Kelly – when the killings stopped – his body was found floating in the river.

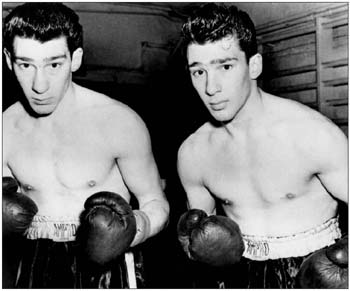

The Kray Twins

T

he Kray twins, Reggie and Ronnie, were probably the nearest London ever came to producing an indigenous Mafia. On the surface they were legitimate businessmen, the owners of clubs and restaurants haunted by the fashionable rich. But in reality they were racketeers and murderers, protected from prosecution by their reputation for extreme violence.

They were born in the London’s East End in 1933 – and soon had a reputation as fighters. Both became professional boxers and, after a brief stint in the army, bouncers at a Covent Garden nightclub. It was then that they started in the protection business, using levels of intimidation that were, to say the least, unusual for their time. Their cousin Ronald Hart later said of them:

‘I saw beatings that were unnecessary even by underworld standards and witnessed people slashed with a razor just for the hell of it.’

In 1956, Ronnie Kray was imprisoned for his part in a beating and stabbing in a packed East End pub, and judged insane. But three years later he was released from his mental hospital, and the twins were back in business, cutting a secret swath of violence through the British capital while being romanticized in the British press – along with people like actors Michael Caine and Terence Stamp – as East-End-boys-made-good. When they were arrested in 1965 for demanding money with menaces, a member of the British aristocracy actually stood up in the House of Lords and asked why they were being held for so long without trial. They were ultimately acquitted.

The Krays were, and still are, immensely popular figures