100 Most Infamous Criminals (32 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

By this time Palmer had been arrested for debt on a charge brought by one of his creditors. Now he was sent to Stafford Prison to await the exhumation of his wife’s and brother’s corpses. The whole of England was abuzz with news of his crimes; and a special Act of Parliament was passed to have him brought to London for trial. The courtroom there was packed and thousands of copies of the transcripts were sold, most of it full of the medical jargon of conflicting experts. For though it was by now known that Palmer had bought strychnine at the time of Cook’s death, no trace of it was ever found in his body. The experts gave different reasons for this – and Palmer wouldn’t help. All he ever said on the subject was:

‘I am innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnine.’

It didn’t matter. He was sentenced to death and hanged in front of Stafford Jail on June 14th 1856, with an audience of almost 30,000 people, some in expensive reserved seats. By that time it had been remembered that all of Palmer’s children but one had died young of convulsions – and so had at least two of his bastards.

Michael Ryan

I

n 1987, Michael Ryan was 27 years old – and a patchily employed farm labourer in Hungerford, west of London. He was ill-educated, morose. His only real passion in life was for guns. He was a member of the local rifle and pistol club where he’d show off his marksmanship and boast to anyone who would listen about his collection of guns – which he kept, fully licensed, in the house he shared with his mother.

No one knows what tipped Michael Ryan over the edge – the best that anyone can come up with is that he was still deeply depressed about the death of his father two years before. But on August 19th 1987, dressed in a military flak jacket and carrying a belt of ammunition, he drove to a nearby forest and, using a 9-mm pistol, shot dead a young woman who was picnicking there with her two children. Then he drove back home, shot both his mother and the family dog and set the house on fire. Picking up his AK-47 from the shed outside, he set out on a leisurely walk through Hungerford.

Who they were didn’t matter. He simply killed whoever he saw: a woman and her daughter driving past; a dog-walker; an elderly man working in his garden; another man on his way to the hospital to see his newborn child. In just ten minutes, Michael Ryan calmly killed sixteen people and wounded another fourteen.

The police put up roadblocks and brought in a helicopter and Ryan ultimately took refuge, in a strange sort of symbolism, in the elementary school he himself had gone to as a kid. The police tried to talk him out, but for hours he kept them at bay, saying nothing. Then, seven hours after his first murder, he used his gun on himself: he committed suicide.

The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, said famously about what Ryan had done:

‘Dawn came like any other dawn, and by evening it just didn’t seem the same day.’

Amid much hand-wringing, Parliament rushed through tougher legislation governing gun-ownership and rifle and pistol clubs – on the grounds that Michael Ryan had used his guns to kill simply because he owned and practised with them. No one, though, has ever satisfactorily explained what was going through his mind – or why he chose that particular day.

Jack Sheppard

A

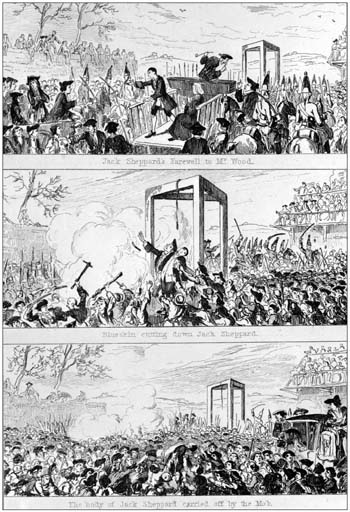

s a highwayman, Jack Sheppard, who was hanged in 1724, was by no means major-league – he seems to have spent just one week at it, and to have carried out only three robberies: of a stage-coach, a lady’s maid and a grocer. He was caught easily enough. But by the time he had escaped four times – once each from St Giles Roundhouse and the New Prison in Clerkenwell, and twice from the Condemned Hold in Newgate – this young brown-eyed thief with an attractive stammer had become the most celebrated criminal in all eighteenth-century Britain.

His adventures were published in pamphlets and broadsheets, as well as in column after column in the newspapers. His portrait was painted by Sir James Thornhill, the most fashionable artist of his day. Daniel Defoe took down from him an account of his life; he inspired a series of pictures by William Hogarth; and when he was finally caught for good, people from both town and country – aristocrats and farmers alike – flocked to Newgate to stare at him as he sat chained and manacled to the floor. There are in London, a journalist wrote in 1724:

‘three great Curiosities. . . viz: the two young Lyons stuff’d at the Tower; the ostrich on Ludgate Hill; and the famous John Sheppard in Newgate.’

In the week before he was hanged, newspaper coverage went up – one journalist wrote: ‘Nothing more at present is talked about Town, than Jack Sheppard.’ The king was even said to have asked for:

‘two prints of Sheppard showing the manner of him being chained… in the Castle in Newgate.’

Such was the publicity that fully 200,000 people turned out to line the processional route he took to the gallows, and after he’d been cut down by the hangman, there were fights over who should have his body. The gang of admirers who finally won it brought him to a City tavern that night, and there was a riot outside that had to be put down by a company of armed Foot Guards.

Within a fortnight, the first of scores of dramatizations of his career opened at Drury Lane; and for the next century and more, fictional versions of his exploits were served up again and again to each successive generation. In 1839, Harrison Ainsworth started publishing his

Jack Sheppard

, which outsold Dickens’

Oliver Twist

. The following year there were no fewer than nine theatrical productions. Well into the twentieth century Jack Sheppard remained alive, wept over by children for his difficult life and cruel fate.

Jack Sheppard became the most celebrated criminal in 18th century England

Dr. Harold Shipman

H

arold Shipman is almost certainly the most prolific serial killer in British history. A public enquiry in 2002 reported that over his career he had probably killed 215 people, mostly women, all of whom had been his patients. For Shipman was a doctor who killed, apparently, simply because he could. His victims were mostly elderly or infirm – they would die sometime, so why not when he dictated? He was caring, after all: a trouble-taker, a pillar of the community always ready to go out of his way to help. So why on earth would anyone suspect him of using the home visits he made to inject his victims with enough heroin or morphine to stop them breathing? No one ever thought to doubt his word and covering his tracks was simplicity itself: all he had to do was doctor his victims’ medical records, if that was necessary, and write a fake cause of death, as their personal GP, on the death certificate. There was no need at all, he’d announce, for a post mortem.

Occasionally Dr. Shipman would be mentioned in his patients’ wills, of course, but that seemed only natural. They mostly didn’t have a great deal of money in the first place; sometimes they had no living family and the doctor, who always worked alone at his surgery in Hyde, Greater Manchester, was the personification of kindness. Then, though, in 1998, he got greedy. For one of his patients, Kathleen Grundy, a woman in her eighties, left him over £380,000. Questions were asked, and the will turned out to have been forged by none other than Shipman himself. He was sentenced to four years in prison.

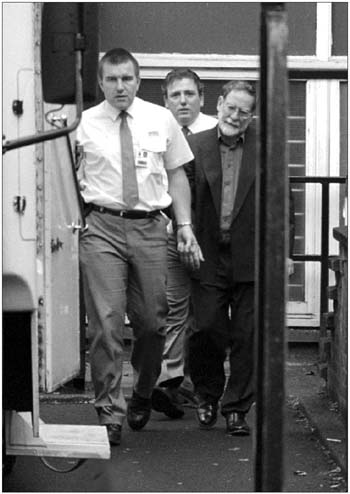

Dr. Harold Shipman, the most prolific serial killer in British history

It was this that triggered a full-scale enquiry. For unlike a great many of his patients – who’d been cremated, along with the evidence in their bones and blood – Kathleen Grundy had been buried. So her body was disinterred and it was found to contain enough heroin to have killed her. Shipman’s records were then seized and searched; relatives of dead patients were interviewed and police began the grisly business of recovering and testing as many corpses as they could locate. The list of those murdered via injections began to rise; and so, to the horror of relatives, friends and patients alike, did the roster of probables.

Shipman, who turned out to have a history of drug addiction, was tried on fifteen counts of murder, all of which he denied; and in January 2000, he was sentenced to life on each count, with the judge adding that, in his case,

‘life would mean life.’

When the subsequent enquiry reported that he had probably been guilty of another 199 murders, he had nothing to say except, again, that he was innocent; at the beginning of 2003, he launched an appeal against his sentence, on the grounds that his legal team hadn’t been allowed to conduct their own post-mortems and that the jury had been wrongly instructed. It seems oddly apt that one of the solicitors involved in his appeal also acted for Slobodan Milosevic.

On January 13th 2004, the eve of his fifty-eighth birthday, Shipman was found hanged in his prison cell.

George Joseph Smith

W

hen George Joseph Smith, the ‘Brides in the Bath’ killer, was put on trial at London’s Old Bailey in June 1915, a surprising number of women showed up to fill the public seats. But then his small eyes were mesmerizing:

‘They were little eyes that seemed to rob you of your will,’

in the words of one of his victims.

Smith was born in the East End of London in 1872 and from the beginning he was a bad lot. At the age of nine, he was sentenced to a reform school for eight years; and by the time he came out, he’d learned all the tricks of the thieving trade. At first he did the thieving himself, but then he discovered his power over women. With a succession of lovers, one of whom he married, he became a small-time Fagin, setting up the robberies they committed and fencing the proceeds.

Ultimately, though, this gambit proved unreliable. For his wife, whom he’d abandoned after she’d been caught and jailed, recognized him one day in a London street, and told the police. He served two years in jail; and when he came out, he turned to a new line of work: using a variety of aliases, he went on an extended tour of the south coast of England, serially seducing women into marriage with him, and then cleaning them out of everything they owned – their savings, their stocks, even their furniture – before he disappeared to start again.

One of these women was thirty-three-year-old Bessie Mundy, a modest heiress whom he ‘married’ in August 1910 and then unceremoniously abandoned, after failing to get his hands on her whole estate. Eighteen months later, completely by chance, she recognized him on the seafront in Weston-super-Mare while staying with a friend and – incredibly – fell for him yet again. They set up house together and this time Smith found a way to get her money. For five days after they’d both signed wills leaving everything they had to each other, Bessie was found ‘drowned’ in the bath. A doctor was called, and then the police – but there seemed no reason to suspect the distraught husband’s story: that he’d gone out to buy some fish and had returned from his expedition to find his wife dead.

Having now got Bessie’s money in its entirety, Smith invested in property in Bristol, where he regularly lived with another of his ‘wives’, pretending to be in the antiques business – and therefore regularly having to travel. By October 1913, though, he needed a fresh injection of cash. So he ‘married’ again, this time a private nurse of 25 with money of her own, and took out an insurance policy on her life. After setting up home together, in December of that year they went on holiday to Blackpool and rented a room in a boarding-house.

In Blackpool, Smith followed more or less exactly the same pattern as in the first murder. First he called in a doctor to consult about his wife’s ‘fits’; then a day later, in the evening, he asked the landlady to run a bath. He then went out ‘to buy eggs for breakfast,’ and returned to find his wife drowned. The doctor was called back to the house, but neither he nor the police nor the coroner at the inquest the next day had any cause to be suspicious. Only the landlady did, for she’d watched what she’d seen as Smith’s callous behaviour. When he left immediately after the funeral – to get rid of his wife’s belongings as quickly as he could – she shouted ‘Dr. Crippen’ at his back. On the guest card he’d filled in, she wrote presciently: