100 Most Infamous Criminals (35 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Less than a month later, on 21 May, a Friday, Suzanne Blamires also vanished. Blamires accompanied Griffiths to his flat, most likely willingly, but then she tried to leave. Security cameras captured her sudden end. Grainy footage shows Blamires fleeing Griffiths’ flat with the PhD student in pursuit. He knocks her unconscious, and leaves her lying in the corridor. Moments later, he returns with a crossbow, aims and shoots a bolt through her head. Before dragging the woman back into his apartment, he raises his crossbow to the camera in triumph. Moments later, Griffiths returns with a drink, apparently toasting the death.

The first person to view these images was the building caretaker. He called the police – but not before first selling the story to a tabloid newspaper.

The first body was discovered by a member of the public in the River Aire. The corpse was cut into at least 81 separate pieces. Police recovered a black suitcase containing the instruments Griffiths had used to carry out the dissection prior to consuming several pounds of flesh. Identification came without the need for DNA testing – Blamires’ head, complete with crossbow bolt, was found in a rucksack. At some point Griffiths had also embedded a knife in her skull.

Griffiths gradually opened up about the murders, providing police with macabre details. He described his flat’s bathtub as a ‘slaughterhouse’, saying that it was there that his victims were dismembered. He used power tools on the first two bodies, boiling the parts he ate in a pot. Blamires was cut up by hand, and her flesh was eaten raw.

Griffiths had filmed his second victim’s death on his mobile phone, which he then left on a train. The device was bought and sold twice before police managed to track it down. The footage it held was described by one veteran detective as the most disturbing he’d ever viewed. Armitage is shown naked and bound with the words ‘My Sex Slave’ spray-painted in black on her back. Griffiths can be heard saying: ‘I am Ven Pariah, I am the Bloodbath Artist. Here’s a model who is assisting me.’

Only Susan Rushworth was spared the indignity of having her death caught on camera. Investigators believe that she was killed with a hammer.

On 21 December 2010, three days before his 41st birthday, Griffiths pleaded guilty to all three murders and was given a life sentence.

Australia

Jack Donohoe

T

he Irish bushranger Jack Donohoe was probably twenty-four years old in 1830, when he was killed by police and a volunteer posse at Bringelly, near Campbelltown outside Sydney. But his memory still endures, kept alive through a popular ballad with hundreds of different variants which lasts down to this day. He became through the ballad the symbol of resistance both to the old convict system and to the British colonial yoke. He is, if you like, both the Jesse James of Australia and, via the heady distillation of the ballad’s lyrics, the first standard-bearer of Australian independence.

Sentenced to transportation in Dublin in 1823 at the age of 17, ‘Bold’ Jack Donohoe was a short, blond, freckle-faced man who, after he arrived in Sydney, seems to have found nothing much but trouble. Having survived the long sea-voyage, he was handed over to a settler in Parramatta, but soon misbehaved: he was sentenced to a stint in a punishment gang to teach him a lesson. Having survived this, he was reassigned, but he took off instead into the bush. In the words of the ballad:

‘He’d scarcely served twelve

months in chains upon the

Australian shore,

When he took to the highway as

he had done before:

He went with Jacky Underwood,

and Webber and Walmsley too,

These were the true companions

of bold Jack Donohoe.’

Donohoe’s gang, to stay alive, held up the carts that travelled, carrying produce to and from the Sydney settlement, along the Windsor Road. He and two of his henchmen were soon caught and condemned to death. The other two were hanged. But Donohoe, while being returned from court to the condemned cell, made a run for it – further contributing to his reputation:

‘As Donohoe made his escape, to

the bush he went straightway.

The people they were all afraid to

travel by night or day,

For every day in the newspapers

they brought out something

new,

Concerning that bold bushranger

they called Jack Donohoe.’

After stealing horses from settlers, a new Donohoe gang began to roam through a huge swath of territory, holding up travellers, thieving from farms and selling off whatever booty they got to whoever would have it. Back in Sydney, he became a stick with which the newspapers could beat the despised Governor’s head. He had armed soldiers and mounted cavalry, they said,

‘but the bushranging gentry seem to carry on their pranks without molestation.’

They even began to lionize Donohoe himself, whom they praised not only for his dress and sense of style, but also for his Pimpernel quality.

‘Donohoe, the notorious bushranger,’ announced the

Australian

,

‘…is said to have been seen by a party well acquainted with his person, in Sydney, enjoying, not more than a couple of days ago… a ginger-beer bottle.’

The Governor was finally forced to act. The price on Donohoe’s head was raised and more police and volunteers were sent into the field. Finally, at Bringelly, they caught up with him:

‘As he and his companions rode

out one afternoon,

Not thinking that the pangs of

death would overtake them

soon,

To their surprise the Horse-Police

rode smartly into view,

And in double-quick time they did

advance to take Jack

Donohoe.’

Before it was all over, according to the ballad, Donohoe shouted out his defiance, saying that he’d never be an Englishman’s slave. He killed nine men with nine bullets before being shot himself through the heart and asking, with his dying breath, all convicts to pray for him. The truth is, of course, more mundane. He did not kill nine men; he screamed nothing much but obscenities; and he was shot in the head by a trooper called Muggleston. But it didn’t matter. For ‘Bold’ Jack Donohoe was already passing into legend. When his body was laid out in the Sydney morgue, the Colony’s distinguished Surveyor-General came in to draw his portrait; and a Sydney shopkeeper produced a line of clay pipes, featuring his head with a bullet-hole at the temple. They sold out fast.

Ned Kelly

N

ed Kelly, a quiet, soft-spoken man, it’s said, was the last and greatest of Australia’s folk-hero bushrangers, with a fanatical hatred of the law. His father, a Victoria farmer, had been transported as a convict from Belfast in Ireland in 1841, and he himself had spent three years in prison as a boy for horse- and cattle-stealing. Whatever the source of the hatred, though, it seems to have boiled over when a police constable arrived at the Kelly farmstead one day in April 1878, looking for his brother Dan. The whole family resisted; the constable was wounded and when a warrant was issued for Ned and Dan Kelly, they took to the bush with two other young tearaways, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne.

In October of that year, they fought a gun battle with a police patrol sent after them at Stringybark Creek. A sergeant and two troopers were killed and from that moment on Ned Kelly, aged just 23, became Australia’s Public Enemy Number One. Identifying him was one thing, though; catching him quite another. For not only did Kelly and his gang have an old and intimate knowledge of the Victoria countryside, they also had many sympathizers – particularly, it’s said, among women – who put them up and passed on information about the police’s whereabouts. When the Kelly gang robbed its first bank at Euroa in December of that year – after taking twenty hostages – the police were 100 miles away on a wild goose chase.

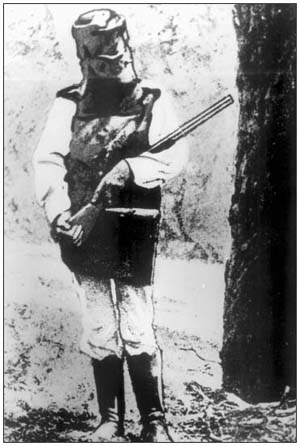

A photograph of Kelly in his armour

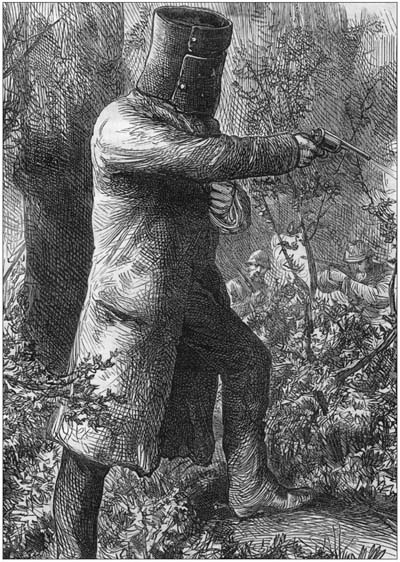

An artist’s impression of Kelly shooting his way out of trouble

In February 1879, in any case, the gang left Victoria for New South Wales and robbed a bank in Jerilderie, with thirty local people locked up in a hotel as insurance. Kelly’s reputation as a brazen and defiant criminal spread, and the police became a laughingstock as he continued to evade capture, despite the arrest of some of his sympathizers and the posting of large rewards. Finally, in June 1880, Kelly decided to humiliate them still further. He sent Joe Byrne to Beechworth, where Byrne calmly shot a former accomplice of the gang, who was supposed to be under police protection. Then he took off, aiming to draw a large body of police into a train ambush at Glenrowan, where Kelly had already taken over sixty hostages and had had a section of the track removed.

Warned by a local schoolmaster, though, the police stopped the train and turned the tables: thirty-seven strong, they ambushed the gang, who were holed up in a hotel with their hostages. Ned Kelly, wounded, escaped into the bush; in the middle of the seven hour siege, during which all the other members of the gang died, he reappeared with his guns – and entered Australian history for ever – wearing black face- and body-armour made from iron plough mouldboards. He was only brought down by being shot in the legs. The armour had taken twenty-five bullets. Asked why he’d come back when he could have escaped, Kelly said:

‘A man gets tired of being hunted like a dog. . . I wanted to see the thing end.’

He was hanged in Melbourne in front of a huge crowd in November 1880 – his last words were:

‘Such is life.’

But not long afterwards his armour was put on show in Hobart, Tasmania in an ex-convict ship, along with waxworks and mementoes of the convict-transport system. The ship, which was later moved to Sydney, was scuttled there, armour and all, by indignant citizens who didn’t want to be reminded of such things.

Katherine Knight

K

atherine Knight had a talent for decapitating pigs. The razor sharp boning knives she had used in her working life in the abattoirs of New South Wales would be the very same tools she later employed to kill her common-law husband.

Knight exhibited a terrifying streak of violence in the years leading up to the murder. She would cut up boyfriends’ clothes and vandalize their cars in fits of rage. There were reports too of her involvement in strangulation, stabbing, burning and savage beatings. She once placed her first-born, Melissa, on railway tracks minutes before a train was due – because the father had walked out on her, driven away by Katherine’s jealousy and violent behaviour. (The two-month-old baby only escaped almost certain death because a local drifter happened to come along at the right time.) A few days later, she disfigured a 16-year-old girl’s face with a butcher’s knife. Later, she would further practise her slaughter skills on her partner’s eight-week-old puppy, cutting its throat in front of her horrified boyfriend.

In 1994, Knight met John Price, known as ‘Pricey’. He was a well-liked man; even his former wife, with whom he’d had four children, spoke of him only in glowing terms. The relationship with Katherine was not easy – the couple often had terrible fights – but six years later Kath and Pricey were still together. By early 2000, though, Pricey began to share his concerns about the relationship with friends and colleagues. He even told a local magistrate that he feared for his life, showing him a stab wound he’d received from Kath. The end of their tempestuous union would come on February 29th 2000.