1968 (24 page)

It seemed the literary capital of writers who had opposed wars, any wars, was on the rise. Hermann Hesse, the German pacifist who moved to Switzerland to evade military service in World War I, was enjoying a popularity among youth greater than he had known during most of his life. Although he died in 1962, his novels, with an almost Marcusian sense of the alienating quality of modern society and a fascination with Asian mysticism, were perfectly suited to the youth of the late sixties. He might have been amazed to discover that in October 1967 a hard-driving electric rock band would name itself after his novel

Steppenwolf.

According to the twenty-four-year-old Canadian lead singer, guitar and harmonica player, John Kay, the group, best known in 1968 for “Born to Be Wild,” had a philosophy similar to that of the hero of the Hesse novel. “He rejects middle-class standards,” Kay explained, “and yet he wants to find happiness within or alongside them. So do we.”

In 1968, it seemed everyone aspired to be a poet. Eugene McCarthy, senator and presidential candidate, published his first two poems in the April 12 issue of

Life

magazine. He said that he had started writing poetry about a year before. Since no one in the working press believes that a politician does anything just by chance in an election year,

Life

magazine columnist Shana Alexander pointed out, “Lately McCarthy has discovered, with some surprise, that people who like his politics also tend to like poetry. Crowds surge forward eagerly when they learn Robert Lowell is traveling with the candidate.”

This turn toward verse showed in McCarthy an understanding of his supporters that was surprising in a candidate who was seldom caught doing anything to curry favor. Most of the time, conventional political professionals and the journalists who covered them did not understand him at all. McCarthy would skip speeches and events without warning. When television host David Frost asked him what he wanted his obituary to say, McCarthy answered without the least suggestion of irony, “He died, I suppose.” His tremendous popularity on college campuses and among the youth who did not like conventional politics initially arose because, until Kennedy entered the race, he was the only candidate committed to an immediate end to the Vietnam War. Early in his campaign, the antiwar leftists such as Allard Lowenstein, who had constructed his candidacy, were so frustrated by the senator’s ambiguous style and lack of passion that they started to fear they had picked the wrong man. Some thought they should appeal to Bobby Kennedy, Lowenstein’s first choice, one last time. But McCarthy’s style appealed to young people who disliked leaders and appreciated a candidate who didn’t act like one. They talked about him as though he were a poet who later became a senator, although the less romantic truth that he was able to reinvent himself as a poet in midcampaign may be a more impressive stunt.

It was

Life

’s Shana Alexander who had labeled him a “conundrum,” explaining, “One’s first response to him is surprise. Admiration, if it comes, comes later.” Perhaps part of his appeal to college students was that he looked and sounded more like a professor than a candidate. Asked about the riots in the black Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, he mystified everyone by comparing them to a peasant uprising in 1381.

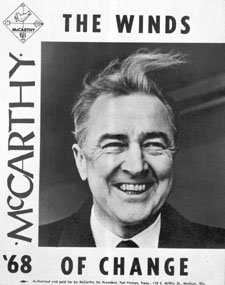

“McCarthy for President” campaign poster, 1968

(Chicago Historical Society)

Norman Mailer, in describing the candidate’s faults at the campaign’s final hours in Chicago, may have hit on exactly the source of his appeal to young antiwar activists of 1968:

He spoke in his cool, offhand style, now famous for its lack of emphasis, lack of power, lack of dramatic concentration, as if the first desire of all men must not be the Presidency, but the necessity to avoid any forcing of one’s own person (as if the first desire of the Devil might be to make you the instrument of your own will). He had insisted after all these months of campaigning that he must remain himself, and never rise to meet the occasion, never put force into his presentation because external events seemed to demand that a show of force of oratorical power would here be most useful. No, McCarthy was proceeding on the logic of the saint, which is not to say that he necessarily saw himself as one (although there must have been moments!) but that his psychology was kin: God would judge the importance of the event, not man, and God would give the tongue to speak, if tongue was the organ to be manifested.

Given how unusual a year this was, it may have made sense for McCarthy to publish his poetry in midcampaign, but the contents of the poem seem ill chosen. Why would someone running for the office of president of the United States volunteer that he felt mired in Act II and could not write Act III? Asked to explain his poem, why he could not write the third act, he said, “I don’t really want to write it,” which for many supporters, reporters, and political professionals confirmed the suspicion that he did not really want to be president. But the senator mused on, “You know the old rules: Act I states the problem, Act II deals with the complications, and Act III resolves them. I am an Act II man. That’s where I live. Involution and complexity.”

McCarthy mused further about everyone from Napoleon to FDR and finally came to his rival Robert Kennedy. “Bobby is an Act I man. He says here’s a problem. Here’s another problem. Here’s another one. He never really deals with Act II, but I think maybe he’s beginning to write Act III. Bobby’s tragedy is that to beat me, he’s going to have to destroy his brother. Today I occupy most of Jack’s positions on the board. That’s kind of Greek, isn’t it?”

Whatever similarities existed between Gene McCarthy and the late John Kennedy, they were seen by few other than the Minnesota senator himself. On the other hand, Bobby Kennedy, many hoped, might be like his brother. But others appreciated that he was not in any way like his older brother Jack except for the Cape Cod Yankee accent and a trace of family resemblance around the eyes. Robert was born in 1925, eight years after Jack. He was not entirely a part of the World War II generation because he had been too young to serve, though his adolescence was steeped in the thinking and experiences of that time, including having his brother, ten years older, killed in combat. By 1950 he was already twenty-five, too old to experience childhood or adolescence in the 1950s. So he was born on a cusp, not quite one generation or the other, tied to the older generation by his family. In the 1950s he participated in the cold war, even serving as a lawyer for the infamous anticommunist senator Joseph McCarthy. The relationship did not last long, and Kennedy would later describe it as a mistake. He said that though misguided, he had been genuinely concerned about communist infiltration. But perhaps a better explanation lay in the fact that his father had gotten him the job.

Robert Kennedy struggled to live up to his father and his big brothers. Having missed World War II, he always admired warriors, men at war. In 1960 at a Georgetown party he was asked what he would like to be if he could do it all over again, and he said, “A paratrooper.” He lacked his big brothers’ ease and charm. But he was the one who understood how to use television for the charming president, arranging for John Kennedy to be the first television president by hiring the first media adviser ever employed by a White House. John, understanding little of television, was a natural because he was easy, relaxed, and witty, and he smiled handsomely. Little brother Bobby, who understood television perfectly well, was terrible at it, looking awkward and intense because he was awkward and intense. John used to laugh at Bobby’s serious nature, calling him “Black Robert.” Seeing how it turned out, it is now easy to think that, with his sober intensity, he always looked like a man slated for a cruel destiny. “Doom was woven in your nerves,” Robert Lowell wrote of him.

He was slight, lacking the robust appearance of his brothers, and unlike his brothers, he was genuinely religious, a devout Roman Catholic, and a faithful and devoted husband. He loved children. Where other politicians would smile with babies or strike an instructive pose with children, Bobby always looked as though he wanted to run off and play with them. Children could sense this and were happy and uninhibited around him.

How did this man who worshiped warfare, wished he had been a paratrooper, was a cold warrior, even authorizing wiretaps on Martin Luther King because he feared he had communist ties—how did he become a hero of the sixties generation and the New Left? There was a moment when Tom Hayden had considered calling off the plans for Chicago demonstrations if Bobby was to be nominated.

In 1968 Robert Kennedy was forty-two years old and seemed much younger. Eight years earlier, when Tom Hayden had walked up to him at the Democratic convention in Los Angeles and brashly introduced himself, the chief impression Hayden walked away with was that he seemed so young. Perhaps that was why the boyhood nickname Bobby always stuck. There was Bobby, at the end of a tough day of campaigning, looking as if he were twelve years old as he settled into his evening ritual of a big bowl of ice cream.

Kennedy was obsessed with self-improvement and probably at the same time with finding himself. He carried books with him to study. For a time it was Edith Hamilton’s

The Greek Way,

which led him to read the Greeks, especially Aeschylus. For a while he carried around Emerson. And Camus had his turn. His press secretary, Frank Mankiewicz, complained that he had little time for local politicians but hours to chat with literary figures such as Robert Lowell, whom he knew well.

Although busy with his campaign, he was eager to meet poet Allen Ginsberg. He listened respectfully as the shaggy poet explained his beliefs about drug enforcement being persecution. The poet asked the senator if he had ever smoked marijuana, and he said that he had not. They talked politics about possible alliances between flower power and Black Power—between hippies and black militants. As the lean senator was walking the stocky, bearded poet to the door of his Senate office, Ginsberg took out a harmonium and chanted a mantra for several minutes. Kennedy waited until Ginsberg fell silent. Then he said, “Now what’s supposed to happen?”

Ginsberg explained that he had just finished a chant to Vishnu, the god of preservation in the Hindu religion, and had thus been offering a chant for the preservation of the planet.

“You ought to sing it to the guy up the street,” said Kennedy, pointing toward the White House.

While he had little chemistry with Martin Luther King and the two always seemed to struggle to speak to each other, he struck up an immediate and natural friendship with the California farmworker leader César Chávez. With the slogan “

Viva la Huelga!

”—“Long Live the Strike!”—Chávez had launched successful national campaigns for what he called

la Causa,

boycotting California grapes and other products to force better conditions for farmworkers. Most self-respecting college students in 1968 would not touch a grape for fear it was a brand being boycotted by Chávez. He had organized seventeen thousand farmworkers and forced their pay to be raised $1.10 an hour to a minimum $1.75. Chávez was a hero of the younger generation, and Kennedy and Chávez, the wealthy patrician and the immigrant spokesman, seemed oddly natural together even if Bobby was famous for ending a rally with “

Viva la Huelga! Viva la Causa!

” and then, his Spanish seemingly failing to match his enthusiasm, “

Viva

all of you.”

Bobby even developed a rapport and sense of humor with the press. His standard campaign speech ended with a quote from George Bernard Shaw, and after a time he noticed the press took this as their cue to go to the press bus. One day he ended a speech, “As George Bernard Shaw once said—Run for the bus.”

He had clearly evolved in profound ways since the death of his brother. He seemed to have discovered his own worth, found the things he cared about rather than the family’s issues, and was willing to champion them even if it meant going against his old allies from those heady and revered days of his still-mourned brother’s administration. To turn against the war had been a deep personal struggle. He had named one of his sons, born in 1965, after General Maxwell Taylor and another in 1967 after Averell Harriman and Douglas Dillon—three of the key figures in pursuing the war.

Even if he was not a great speaker, he said extraordinary things. Unlike politicians today, he told people not what they wanted to hear, but what he thought they should hear. He always emphasized personal responsibility in much the same terms, with a similar religious fervor, as did Martin Luther King, Jr. Championing the right causes was an obligation. While adopting a strong antiwar position, he criticized student draft dodgers, going onto campuses where he was met by cheering crowds and lecturing them on passing on their responsibilities to less privileged people by refusing the draft. But he also said that those who did not agree with what their government was doing in Vietnam were obligated to speak out because in a democracy the war was being carried on “in your name.”

McCarthy did some of this as well, telling his young supporters that they had to work hard and look better for the campaign. Supporters cut their hair, lowered hemlines, and shaved their faces to get “clean for Gene.”