1968 (28 page)

The American press, once accused of coddling the bearded heroes, had turned so vehemently against the revolution, once they understood that it

was

a revolution, that Robert Taber, the CBS correspondent who had met with Castro in the mountains, decided to form an organization called Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Unfortunately, the short-lived organization is most remembered by the odd and unexplained evidence that Lee Harvey Oswald, John Kennedy’s assassin, participated in it. But there was something more interesting about the group. Taber, by most accounts, was fairly apolitical and simply believed that the Cuban revolution was initiating interesting social and economic changes that were being ignored by the press. Among those he attracted to the organization were Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Norman Mailer, James Baldwin, theater critic Kenneth Tynan, and Truman Capote. The group placed high-profile ads explaining the Cuban revolution. With very little political affiliation except for the French couple who were connected to the French Communist Party, they were still able to attract thousands of people to write-in campaigns and demonstrations. It was one of the first indications that the United States had a large body of left-leaning people who were not part of any leftist establishment—the people who came to be known as the New Left.

During the first two years of Castro’s rule, the rift between Washington and Havana widened steadily. In early 1959 there were already hints of a U.S. invasion, and Castro made his famous remark about “two hundred thousand dead gringos” if they tried. On June 3, 1959, Cuba’s Agrarian Reform Law limited the size of holdings and required owners to be Cuban. Sugar company stocks on Wall Street immediately crashed, while the U.S. government angrily and futilely protested. In October, Major Huber Matos and a group of his officers were arrested for their anticommunist political stances, stances that had matched Castro’s own a year earlier, and tried for “uncertain, anti-patriotic, and anti-revolutionary conduct.” By November 1959 the Eisenhower government had decided on the forcible removal of Castro and began working with Florida exiles toward that goal. Two months later the Fair Play for Cuba Committee began its activities. In February 1960 Cuba signed a five-year accord with the Soviet Union to trade Cuban sugar for Soviet industrial goods. Only a few weeks later a French ship,

Le Coubre,

carrying rifles and grenades, blew up in Havana harbor owing to causes still unknown today, killing seventy-five and injuring two hundred Cuban dockworkers. Castro declared a day of mourning, accusing the United States of sabotage, though he admitted that he had no proof, and in one of his more famous speeches said, “You will reduce us neither by war nor famine.” Sartre, visiting Cuba, wrote that in the speech he found “the hidden face of all revolutions, their shaded face: the foreign menace felt in anguish.”

The United States called back its ambassador, and Congress gave Eisenhower the power to cut the Cuban sugar quota, which Eisenhower insisted he would do not to punish the Cubans, but only if necessary for regulating U.S. sugar supplies.

On May 7 Cuba and the Soviet Union established diplomatic ties, and during the summer U.S.-owned refineries that refused to take Soviet oil were nationalized. When the Soviet Union pledged to defend Cuba from foreign aggression, Eisenhower dramatically cut the Cuban sugar quota. It appears that Cuba’s drift toward the Soviet Union was fueling U.S. hostility, but in fact it is now known that back in mid-March, before the ties with Moscow were established, Eisenhower had already approved a plan for an exile invasion of the island. Throughout the 1960 summer election campaign, John Kennedy repeatedly accused the Republicans of “being soft” on Cuba.

On October 13, 1960, Cuba nationalized all large companies, and the following week, while Kennedy accused Nixon and the Eisenhower administration of “losing” Cuba, Eisenhower responded with a trade embargo, which Castro answered by nationalizing the last 166 American-owned enterprises on the island. By the time Kennedy was inaugurated in January, the U.S.-Cuban relationship appeared to have already reached the point of no return. Kennedy cut diplomatic relations with Cuba, banned travel to the island, and demanded that the Fair Play for Cuba Committee register as a foreign agent, which it refused to do. But Kennedy boasted, “We can be proud that the United States is not using its muscle against a very small country.” Kennedy was different, a liberal with “a new frontier.”

Then he did exactly what he had been proud of not doing, authorizing the invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles. The so-called Brigade 2506, on April 17, was an extraordinary disaster. The exiles had convinced the United States that the Cubans would rise up against Castro and join them. But they didn’t. Instead they rose up with impressive determination to defend their island against a foreign invader. The Cuban exiles also thought that if they got into trouble, the U.S. military would step in, which Kennedy was not willing to do. In three days, what came to be known as the Bay of Pigs invasion was over. Fidel had saved Cuba. As Dean Acheson so succinctly put it, “It was not necessary to call on Price Waterhouse to know that 1,500 Cubans wasn’t as good as 250,000 Cubans.”

The Bay of Pigs was an enormously significant moment in postwar history. It was America’s first defeat in the third world. But it also marked a shift that had been taking place since the end of World War II. The United States had been founded on anticolonialism and had been lecturing Europe on its colonialist policies even as recently as Franklin Roosevelt. All the while, it had been developing an imperialism of its own—ruthlessly manipulating the Caribbean, Latin America, and even parts of Asia for its own benefit with indifference to the plight of the local inhabitants—while the Europeans, against their will, had been losing their colonies. America was becoming the leading imperialist.

At the time of the Bay of Pigs, France had lost a colonial war with Vietnam and was mired in one with Algeria. The year before, the British had given up fighting the Mau Mau and were now planning for Kenyan independence. The Belgian Congo was in a bloody civil war over its independence. The Dutch were fighting an independence movement in Indonesia and New Guinea. These were European problems, and a New Left in Europe was organizing over the issue of anticolonialism and the struggles of newly emerging nations. The Bay of Pigs brought the United States solidly into this debate, making writers such as Frantz Fanon, not to mention Ho Chi Minh, relevant to Americans and shaping the way the young Left in the United States and around the world would see Vietnam. To them the Bay of Pigs made Cuba a symbol of anticolonialism. The issue was no longer the quality of the Cuban revolution, but just the fact of it and that it had stood up to a huge imperialist nation and survived.

The Bay of Pigs invasion also drove a wedge between the liberals and the Left, who had united for a moment in the promise of a Kennedy presidency. Norman Mailer, a prominent Kennedy supporter and chronicler, wrote in an open letter, “Wasn’t there anyone around to give you the lecture on Cuba? Don’t you sense the enormity of your mistake—you invade a country without understanding its music.” But it is significant that in the numerous protests against the invasion that took place around the country, a great many of the protesters were college students who had not been particularly political up until then. By his fourth month in office, it had become clear that the Kennedy administration was not just about the New Frontier, the Peace Corps, and the race to the moon. Exactly like his predecessor, this president wanted to use military power to back up cold war obsessions and would have no tolerance for small, impoverished countries that did not step into line. Young Kennedy enthusiasts such as Tom Hayden would soon start reappraising their support of him. Even the Peace Corps looked different. Was it really an organization by which people with ideals could help the newly emerging nations? Or was it a wing of U.S. government policy, which was colonialist and not, as it had always claimed, anticolonial?

The Bay of Pigs was one of the defining moments in a new generation’s cynicism about liberals. By 1968 “liberal” had become almost synonymous with “sellout,” and singer Phil Ochs amused young people at demonstrations with his song “Love Me, I’m a Liberal.” The song’s message was that liberals said the right things but could not be trusted to do them.

Fidel Castro is a seducer. He has always had an enormous ability to charm, convince, and enlist. He was so completely confident and self-assured that he was almost an irresistible force. He could just walk into a room or even a wide-open space and everyone present could feel, even in spite of themselves, a sense of excitement—a sense that something interesting was about to happen. He understood very well how to use this talent, made more important because he, and everyone else, had started to view the revolution as an extension of himself. Cuba too had a long history of seducing visitors, with its beauty and the richness of its culture, the grandeur of its capital like no other Caribbean city. And Fidel, who had been cheered on American college campuses, knew that Cuba still had a wealth of young supporters in the United States.

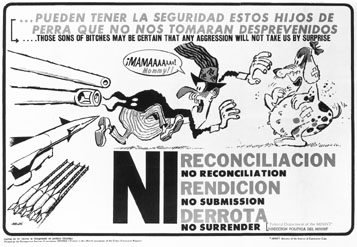

Cuban government poster, 1968

(Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

For all these reasons it became Cuban policy to bring over as many sympathetic Americans as possible to show them the revolution firsthand. Travel restrictions and economic embargoes could be circumvented by Cuban government–sponsored trips. Most of the visitors understood that the Cubans were out to seduce them. Some resisted and others didn’t care to go. In either case, the result was usually the same. Most left deeply impressed with the Cuban revolution: the elimination of illiteracy, the construction of new schools across the island, the development of an extensive and effective health care system. The Cubans even experimented with feminism—increased roles for women, an antimachismo campaign, marriage vows in which the man pledged to help clean the house. These social experiments to build “a new man” were striking. And while it was a young revolution, it had a contagious excitement.

Most saw things that were wrong—too many police, too many arrests, no free press. But they also saw so much that was extraordinarily bold and experimental and inspiring. They were well aware that Cuba’s enemies, chiefly the U.S. government and Cuban exiles, were opposed to the revolution not for the things that were wrong, but for the things that were right, and this made them focus on these important transformations.

Susan Sontag spent three months in Cuba in 1960 and found the country “astonishingly free of repression.” While noting a lack of press freedom, she applauded the revolution for not turning against its own, as did so many revolutions. This would have been inspiring news to Huber Matos, serving his twenty-five-year term, or the fifteen thousand “counterrevolutionaries,” many of them former revolutionaries, who were in Cuban prisons in the mid-1960s. But because leftists believed Cuba was being treated so unfairly by the same U.S. government that was brutalizing Vietnam, and because they were both infuriated by the United States and impressed by the genuine accomplishment of Castro, they had a tendency to overstate the case for Cuba. Some felt that they were only compensating for the obvious lies and misstatements of Cuba’s enemies.

Cuba transformed LeRoi Jones. Born in 1934, he spent the fifties as a beat poet, focused on neither race nor revolution. In fact, he was less political than his colleague Allen Ginsberg, with whom he founded a poetry magazine in 1958. In 1960 he went on one of the Cuban-sponsored trips, this one for black writers. Like many other writers on such Fidel-sponsored junkets, he worried about being “taken” the way it was always said Herbert Matthews had been. “I felt immediately sure that the make was on,” he wrote. It was hard not to feel that way as a guest of the government, shuttled from one accomplishment to the next by the Casa de las Americas, a government organization of earnest, well-educated young people who could talk about Latin American art and literature. The Casa was run by Haydée Santamaria, who had been a member of Castro’s inner group since the beginning. Santamaria, later infamous for the persecution of insufficiently revolutionary Cuban writers, believed that it was impossible to be an apolitical writer, since being apolitical was in itself a political stance. Jones had been initially disappointed by the caliber of black writers on the trip. He was the most distinguished. But he was struck by his contact with Latin American writers, some of whom attacked him for his lack of political commitment. The final step appeared to be on July 26, the anniversary of Castro’s 1953 quixotically unsuccessful attack on an army fortress that had kicked off the revolution. After touring the Sierra Maestras with a group of Cubans celebrating the anniversary, he returned and described the scene in an essay, “Cuba Libre.”

At one point in the speech the crowd interrupted for about twenty minutes, crying, “Venceremos, venceremos, venceremos, venceremos, venceremos, venceremos, venceremos, venceremos.” The entire crowd, 60 or 70,000 people, all chanting in unison. Fidel stepped away from the lectern, grinning, talking to his aides. He quieted the crowd with a wave of his arms and began again. At first softly, with the syllables drawn out and enunciated, then tightening his voice and going into almost a musical rearrangement of his speech. He condemned Eisenhower, Nixon, the South, the Platt Amendment, and Fulgencio Batista in one long, unbelievable sentence. The crowd interrupted again, “Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel, Fidel.” He leaned away from the lectern, grinning at the Chief of the Army. The speech lasted almost two and a half hours, being interrupted time and again by the exultant crowd and once by five minutes of rain. When it began to rain, Almeida draped a rain jacket around Fidel’s shoulders, and he relit his cigar. When the speech ended, the crowd went out of its head, roaring for almost forty-five minutes.