1968 (31 page)

It seemed America was divided into two kinds of people: those who lived the new way and those who were desperate to understand it. The secret of the surprise theatrical success

Hair,

“the American tribal love-rock musical,” was that although virtually nothing happens in the course of it, it claimed to offer the audience a glimpse of hippie life, furthering the stereotype that hippies do absolutely nothing and do it with an inexplicable—surely drug-induced—enthusiasm. Newspapers and magazines often ran exposés on campus life. Why was Abbie Hoffman’s wed-in covered in

Time

magazine? Because the news media and the rest of society’s establishment were trying to understand “the younger generation.” It was one of the “big stories of the year,” along with the war they were refusing to fight. Magazines and newspapers regularly ran articles on “the new generation.” Most of these articles had an undertone of frustration because the reporters could not understand whose side these people were on. To the establishment, they seemed to be against everything. An April 27, 1968, editorial in

Paris Match

said, “They condemn Soviet society just like bourgeois society: industrial organization, social discipline, the aspiration for material wealth, bathrooms, and, in the extreme, work. In other words, they reject Western society.”

In 1968, a book was published in the United States called

The Gap,

by an uncle and his longhaired, pot-smoking nephew trying to understand each other. The nephew introduces the uncle to marijuana, which the uncle queerly refers to as “a stick of tea.” But after he smoked it he said, “It expanded my consciousness. No kidding! Now I know what Richie means. I listened to music and heard it as never before.”

Ronald Reagan defined a hippie as someone who “dresses like Tarzan, has hair like Jane, and smells like Cheetah.” The lack of intellectual depth in Ronald Reagan’s analysis surprised no one, but most of these analyses had little more to them. Society had not progressed beyond the 1950s, when the entire so-called beat generation, a phrase invented by novelist Jack Kerouac, was reduced on television to a character named Maynard G. Krebs, who seldom washed and would croak, “Work!?” in a horrified tone any time gainful employment was suggested. Norman Podhoretz had written an article in the

Partisan Review

on the beat generation titled “The Know-Nothing Bohemians.” A rejection of materialism and a distaste for corporate culture were dismissed as not wanting to work. A persistent claim of a lack of hygiene was used to dismiss a different way of dressing, whereas neither beatniks nor hippies were particularly dirty. True, the occasional Mark Rudd was known for slovenliness, but many others were neat, even fastidious—obsessed with hair products for their new flowing locks and preening in embroidered bell-bottoms.

The public had a fixation on the subject of hair length, which gave the 1968 Broadway show its title. In 1968 there was actually a poster placed on two thousand billboards across the country that had a picture of a bushy-headed eighteen-year-old and said, “Beautify America, Get a Haircut.” Joe Namath, the New York Jets quarterback, with medium-length hair and sometimes a mustache—whose courage and toughness did much to elevate football to a leading national sport in the late 1960s—was frequently greeted in stadiums by fans with signs saying, “Joe, Get a Haircut!” In March 1968, when Robert Kennedy was wrestling with a decision about running for president, he received letters saying that if he wanted to be president, he should get a haircut. There was an oddly hostile tone to these letters. “Nobody wants a hippie for President,” one said. And, in fact, when he declared his candidacy, he did get a haircut.

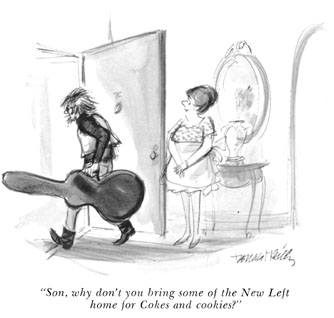

Playboy,

March 1968

(Reproduced by special permission of

Playboy

magazine. Copyright © 1968 by

Playboy

)

By 1968, a wide range of commercial interests realized that “the generation gap” was a concept that could be marketed for profit. ABC Television launched a new series called

The Mod Squad,

seemingly unaware that “mod” was an already dated British word. The series was about three young cops—one looking like a young version of Mary from the folk-singing group Peter, Paul, & Mary, another like a cleaned-up young Bob Dylan, and the third like a sweet-faced Black Panther—all the provocative, violent, and churning counterculture suddenly rendered absolutely harmless. ABC’s advertisements said, as though people actually talked like this, “The police don’t understand the now generation—and the now generation doesn’t dig the fuzz. The solution—find some swinging young people who live the beat, get them to work for the cops.” The ABC ad went on to explain, “Today in television the name of the game is think young. . . . And with a whole breed of young adult viewers, ABC wins hands down.”

In 1968 everyone held opinions on the generation gap, Columbia president Grayson Kirk’s phrase from an April 12 speech at the University of Virginia that instantly became banal. André Malraux, who in his youth was known as a fiery rebel but in 1968 was part of de Gaulle’s right-wing government, denied that there was a gap between generations and insisted the problem was the normal struggle of youth to grow up. “It would be foolish to believe in such a conflict,” he said. “The basic problem is that our civilization, which is a civilization of machines, can teach a man everything except how to be a man.” Supreme Court chief justice Earl Warren said in 1968 that “one of the most urgent necessities of our time” was to resolve the tensions between what he called “the daring of youth” and “the mellow practicality” of the more mature.

Then there were those who explained that the youth of the day were simply in transition to a postindustrial society. Added to the widely held belief that the new youth, the hippies, were unwilling to work was the belief that they would not have to. One study by the Southern California Research Council claimed that by the year 1985 most Americans would have to work only half the year to maintain their current standard of living and warned that recreational facilities were woefully underdeveloped for all the leisure time facing the new generation. These conclusions were based on the rising individual share of the gross national product. If the total value of goods and services was divided by the total population, including nonearners, the resulting figure was projected to double between 1968 and 1985. It was a widespread belief in the 1960s that American technology would create more leisure time, Herbert Marcuse being one of the few to argue that technology was failing to create leisure time.

John Kifner, a young

New York Times

reporter respected by student radicals at Columbia, wrote a January 1968 article from Amherst on marijuana and students, which contained the shocking news that the town was selling a great deal of Zig-Zag cigarette paper and no pouches of tobacco. The article introduced readers to the concept of recreational drugs. These students were doing drugs not to forget their troubles, but to have fun. “Interviews with students indicated that, while many drug takers appeared to be troubled, many did not.” The article suggested that the drug lifestyle had been encouraged by media coverage. A high school principal in affluent suburban Westchester was quoted as saying, “There’s no doubt this thing has increased since the summer. There were articles on the East Village in

Esquire, Look,

and

Life

and this provides the image for the kids.”

Such articles described “college marijuana parties,” although a more typical get-together would be students lying around smoking joints and reading such an article while uncontrollable giggling led to gasping, wheezing laughter. A popular way to pass a rainy day in the East Village was to get stoned and go to the St. Marks Cinema, where sometimes included in the triple feature for a dollar would be the old documentary on the dangers of marijuana,

Reefer Madness.

Marijuana was a twentieth-century drug in the United States. It had never even been banned by law until 1937. LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide, or acid, was invented by accident in a Swiss laboratory in the 1930s by a doctor, Albert Hofmann, when a small amount of the compound on his fingertips resulted in “an altered state of awareness of the world.” After the war, Hofmann’s laboratory sold small amounts in the United States, where saxophonist John Coltrane, celebrated for his introspective brilliance, jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and pianist Thelonious Monk experimented with the new drug, though not nearly as much as did the CIA. The substance was hard to detect because it had neither odor, taste, nor color. An enemy surreptitiously exposed to LSD might reveal secrets or become confused and surrender. This was the origin of the idea of slipping acid into the water cooler. Plans under consideration included slipping acid to Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser and Cuba’s Fidel Castro so that they would babble foolishly and lose their followings. But Castro’s popularity among the young would probably have been enormously magnified once Allen Ginsberg and others learned that Fidel, too, was an acid head.

Agents experimented on themselves, causing one to run outside to discover that cars were “bloodthirsty monsters.” They also, in conjunction with the army, experimented on unknowing victims, including prisoners and prostitutes. The tests resulted in a number of suicides and psychotic patients and left the CIA convinced that it was almost impossible to usefully interrogate someone while under the influence of LSD. Acid experiments were encouraged by Richard Helms, who later, between 1967 and 1973, served as CIA director.

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, Harvard junior professors, studied LSD by taking it or giving it to others. Their work in the early sixties was well respected—until parents started complaining that their promising young Harvard student was boasting of having “found God and discovered the secret of the Universe.” The pair left Harvard in 1963 but continued experiments in Milbrook, New York. In 1966 LSD became an illegal substance by an act of Congress and Leary’s fame spread through arrests. Alpert became a Hindu and changed his name to Baba Ram Dass. In 1967, Allen Ginsberg urged everyone over the age of fourteen to try LSD at least once. Tom Wolfe’s bestselling book that extolled and popularized LSD,

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,

was published in 1968.

It was an unpredictable drug. Some people had a pleasant experience and others nightmarish cycles of mania and depression or paranoia known as “a bad trip.” Students who took pride in being responsible drug abusers insisted that tripping be done under the supervision of a friend who did not take the drug but had experienced it before. To many, including Abbie Hoffman, there was a kind of unspoken fraternity of those who had taken acid, and those who had not were on the outside.

Disturbing stories began to appear in the press. In January 1968 several newspapers reported that six young college men suffered total and permanent blindness as a result of staring at the sun while under the influence of LSD. Norman M. Yoder, commissioner of the Office of the Blind in the Pennsylvania State Welfare Department, said the retinal area of the youths’ eyes had been destroyed. This was the first case of total blindness, but in a case the previous May at the University of California at Santa Barbara, four students reportedly lost reading vision by staring at the sun after taking LSD. But many stories of LSD damage proved bogus. Army Chemical Corps testing failed to support the ubiquitous stories of LSD causing chromosome damage.

Acid was having a profound effect on popular music. The Beatles’ 1967

Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

album reflected in music, lyrics, and cover design the drug experiments of the group. Some of the songs were descriptive of fantasies experienced while under the influence of LSD. This was also true of the earlier song “Yellow Submarine,” which was the basis of a 1968 movie. John Lennon’s first imaginary voyage in a submarine was reported to be the result of an acid-doused sugar cube. To the audience, Sergeant Pepper was about drugs, one of the first of the acid albums—the coming of age of psychedelic music and psychedelic album design. Perhaps because of the drug use that went with listening to this music,

Sergeant Pepper

was said to have profound implications. Years later Abbie Hoffman said the album expressed “our view of the world.” He called it “Beethoven coming to the supermarket.” But at the time, the ultra- conservative John Birch Society claimed that the album showed a fluency in the techniques of brainwashing that proved the Beatles’ involvement in an international communist conspiracy. The BBC barred the airing of “A Day in the Life” because of the words “I’d love to turn you on” and Maryland governor Spiro Agnew campaigned to ban “With a Little Help from My Friends” because the fab four sang that that was how they “get high.”

The Beatles did not invent acid rock, the fusion of LSD and rock music, but because of their status, they opened the floodgates. San Francisco groups had been producing acid rock for several years but by 1968 a few of these groups such as the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead became famous internationally while many others such as Daily Flash and Celestial Hysteria remained San Francisco acts.