1968 (25 page)

But Kennedy went to extraordinary lengths to define what was wrong and what needed to be done. He attacked the national obsession with economic growth, a statement Hayden cited for its similarity to the Port Huron Statement:

We will find neither national purpose nor personal satisfaction in a mere continuation of economic progress, in an endless amassing of worldly goods. We cannot measure national spirit by the Dow Jones Average, nor national achievement by the Gross National Product. For the Gross National Product includes air pollution, and ambulances to clear our highways from carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and jails for the people who break them. The Gross National Product includes the destruction of the redwoods and the death of Lake Superior. It grows with the production of napalm and missiles and nuclear warheads. . . . It includes . . . the broadcasting of television programs which glorify violence to sell goods to our children.

And if the Gross National Product includes all this, there is much that it does not comprehend. It does not allow for the health of our families, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It is indifferent to the decency of our factories and the safety of our streets alike. It does not include the beauty of our poetry, or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials . . . the Gross National Product measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile, and it can tell us everything about America—except whether we are proud to be Americans.

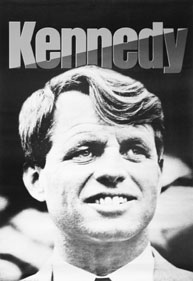

“Robert Kennedy for President” campaign poster, 1968

(John F. Kennedy Library and Museum)

Could a man who said such revolutionary things actually get to the White House? Yes, it was possible, because this, after all, was a Kennedy. Most McCarthy supporters, at their most optimistic, thought the campaign might stop the war but quietly believed their man was unelectable. But Robert Kennedy had a real chance of becoming president, and though historians since have debated on what kind of president he might have been, he was a man the younger generation could relate to and even believe in, a hero even in a year poisoned by King’s murder.

Kennedy had endless energy for campaigning, and he might catch up to and pass McCarthy, he might even beat Hubert Humphrey, the vice president who would certainly pick up Johnson’s mantle and step into the race. Even with that Nixon nightmare—another contest with a Kennedy—pollsters said Bobby could win. If he could catch up to McCarthy in the spring, he might be unstoppable. But then what weighed on Kennedy and most of his supporters and detractors was the thought that he might be unstoppable—unless someone stopped him with a bullet.

CHAPTER 9

SONS AND DAUGHTERS

OF THE NEW FATHERLAND

How will it be to belong to a nation, to work in the spiritual tradition of a nation that never knew how to become a nation, under whose desperate, megalomaniac efforts to become a nation the world has had to suffer so much! To be a German author—what will that be? Back of every sentence that we construct in our language stands a broken, a spiritually burnt-out people . . . a people that can never show its face again.

—T

HOMAS

M

ANN,

“

The Tragedy of Germany

,”

1946

I

T WILL NEVER BE

completely comprehensible to other peoples what it was like to be German and born in the late 1940s, the concentration camps closed, the guilty scattered, the dead vanished. The twenty-first-century public drama of Gerhard Schröder, born in 1944, elected chancellor of Germany in 1998, is a story of his generation. He never knew his father, who died in the war before he was born. How his father died or who he was remained a mystery. While in office as chancellor, Schröder found a faded photograph of his father as a German soldier but could learn little else about him. The possibilities were frightening.

After World War II, when there were not two but four Germanies—the American, British, French, and Russian sectors—the policy in all four sectors was what the Americans called “de-Nazification,” a purge of high and low Nazi officials from all responsible positions and war crime trials for all ranking Nazis.

In 1947 the United States launched its Marshall Plan to rebuild European economies. The Russians declined to participate and soon there were two Germanies and two Europes and the cold war had begun. In 1949 the United States established its own Germany, West Germany, with a capital in Bonn, a city as far as possible from the East. The Soviets responded with an East Germany whose capital was in the divided old capital of Berlin. By July 1950, when the cold war had become a shooting war in Korea, de-Nazification was quietly dropped in West Germany. Nazis, after all, had always been reliable anticommunists. But in East Germany, the purge continued.

There had always been a north and south Germany, Protestants in the north and Catholics in the south, with different foods and different accents. But there had never been an East and West Germany. The new 858-mile border had neither cultural nor historic logic. Those in the west were told they were free, whereas the easterners were oppressed by communism. Those in the east were told that they were part of a new experimental country that was to break with the nightmarish past and build a completely new Germany. They were told that the west was a Nazi state that made no effort to purge its disgraceful past.

Indeed, in 1950 West Germany, with U.S. and Allied approval, declared an amnesty for low-level Nazis. In East Germany, 85 percent of judges, prosecutors, and lawyers were disbarred for Nazi pasts, and most of these resumed their legal profession in West Germany by qualifying for the amnesty. In East Germany, schools, railroads, and post offices had been purged of Nazis. These Germans also were able to continue their careers in West Germany.

To many in both the east and west it was the Globke affair that crystallized how things were to be in the new West German Republic. In 1953 Chancellor Konrad Adenauer chose for state secretary of the Chancellory a man named Hans Globke. Globke was not an obscure Nazi. He had written the legal argument supporting the Nuremberg laws that stripped German Jews of their rights. He had suggested forcing all Jews to carry either the name Sarah or Israel for easy identification. The East Germans protested Globke’s presence in the West German government. But Adenauer insisted that Globke had done nothing wrong, and he remained in German government until he retired to Switzerland in 1963.

In 1968 Nazis were still being discovered.

Edda Göring was in court trying to keep possession of the sixteenth-century painting by Lucas Cranach,

Madonna and Child.

It was of sentimental value since it had been given to her at her christening by her now deceased father, Hermann Göring. Göring, who had stolen the painting from the city of Cologne, had been founder and head of the Gestapo and the leading defendant at the showcase of de-Nazification, the Nuremburg trials. He killed himself hours before the scheduled time of his execution. The city had been trying to get the painting back ever since. Though Edda Göring had lost in court yet again in January 1968, her lawyers predicted at least two more rounds of appeals.

At the same time, evidence surfaced, actually resurfaced, that Heinrich Lübke, the seventy-three-year-old president of West Germany, had helped to build concentration camps. The East Germans had made the accusations two years earlier, but their documents had been dismissed as false. Now

Stern,

the West German magazine, had hired an American handwriting expert who said that the Lübke signatures by the head of state and the Lübke signatures on concentration camp plans were made by the same hand.

By 1968 questioning a high official on wartime activities was not new, except that now it was on television. The French magazine

Paris Match

wrote, “When you are 72 years old, and at the summit of your political career, the highest ranking person of state, and you are shown on television in front of 20 million viewers in the role of the accused, that is the worst.”

In February two students were expelled from the university in Bonn for breaking into the rector’s office and writing on the honor roll next to Lübke’s name “Concentration Camp Builder.” Following their expulsions, a petition signed by twenty of the two hundred Bonn professors demanded that Lübke address the issue publicly. The German president met with the chancellor, the head of government and the more powerful position in the German system. Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger reviewed different options with the president, ruling out retirement or resignation. A few days later the president went on television denying the charges but saying, “Naturally, after nearly a quarter of a century has gone by, I cannot remember every paper I signed.” It took more than ten months before he was finally forced to resign.

Chancellor Kiesinger, who had worked for the government of the Third Reich, had his own problems in 1968. He was called as a witness to the war crimes trial of Fritz Gebhard Von Hahn, accused of complicity in the murder of thirty thousand Greek and Bulgarian Jews in 1942 and 1943. From almost the moment the chancellor took the stand, it appeared that he himself was on trial. The defense had called him to explain that while he was serving in the Foreign Ministry, news on the deportation and killing of Jews was not passed on by his radio-monitoring department. But first he had to explain why he had a position in the Foreign Ministry. He said it was “a coincidence,” but he did admit having been a Nazi Party member. He explained that he had joined the party in 1933, “but not out of conviction or opportunism.” For most of the war, he said, he had thought Jews were being deported to “munitions factories or places like that.” Then did the radio department pass on news about the fate of deported Jews? “What information?” was Kiesinger’s response. He denied knowing anything about killing Jews.

The Kiesinger government had come to power two years earlier in a reasonably successful attempt at a compromise coalition that offered political stability. But it was then that the student movement became most visible. A new generation had been angered and worried by the end of de-Nazification and the decision to remilitarize West Germany. The universities had become crowded owing to a policy, first established by the Allies, of offering military deferments to college students. Yet by 1967, despite growing university enrollment, only about 8 percent of the population attended university, still a small elite. Students wanted to be less elite and demanded that the government open up opportunities for enrollment. In March 1968 the West German Chamber of Commerce and Industry complained that German society risked producing more graduates than the number that could reasonably expect appropriate career opportunities.

On March 2, the day of the announcement, a prosecutor released Robert Mulke from prison on the grounds that the seventy-one-year-old was not in good enough health for prison. Mulke had been convicted three years earlier of three thousand murders while serving as assistant commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp.

In 1968 German student leaders estimated that they had six thousand militant students behind them. But they had the ability to mobilize many thousands more over a variety of issues. The Vietnam War, the illegal military dictatorship in Greece, and oppression by the shah of Iran were the three most popular foreign issues, but German issues occasionally rallied even more protesters. Fritz Teufel’s Commune I organization and a Marxist student study group by coincidence also called SDS, Socialistische Deutsche Studentenbund, were experienced and well organized.

One of the central themes of the student movement was that Germany was a repressive society. The implied word was “still,” Germany was still repressive—meaning it had failed to emerge from the Third Reich and become truly democratic. The presence of Nazis in government was only an underlying part of this. The suspicion on the part of many students that their parents may have either done or countenanced horrendous deeds had created a generation gap far wider and deeper than anything Grayson Kirk was seeing at Columbia.

The fear of the past, or in many cases lack of a past, was recognized by many psychiatrists and therapists as a special problem of Germans of the postwar generation. Sammy Speier, an Israeli-born psychoanalyst in private practice in Frankfurt, wrote, “Since Auschwitz there is no longer any narrative tradition, and hardly any parents and grandparents are left who will take children on their lap and tell them about their lives in the old days. Children need fairy tales, but it is just as essential that they have parents who tell them about their own lives, so that they can establish a relationship to the past.”

One of the surface issues was academic freedom and control of the university. The fact that this often stated issue was not at the root of the conflict is shown by the place where the student movement was first articulated, developed most rapidly, and exploded most violently. Berlin’s Free University was, as the name claimed, the most free university in Germany. It was created after the war, in 1948, and so was not mired in the often stultifying ways of the old Germany. By charter a democratically elected student body voted with parliamentary procedure on the faculty’s decisions. A large part of the original student body were politically militant East Germans who had left the East German university system because they refused to submit to the dictates of the Communist Party. They remained at the core of the Free University so that thirteen years after its founding, when the East Germans began erecting a wall in 1961, students from the Free University in the West attempted to storm the wall. After the wall was built, students from East Germany were unable to attend the Free University and it became largely a school for politicized West German students. With far greater intensity than American students, the students of West Berlin, the definitive products of the cold war, were rejecting capitalism and communism at the same time.

Berlin, partly because it was located at the heart of the cold war, became the center of all protest. East Germans were slipping into West Berlin, West Germans were slipping into the east. This second traffic was less talked about, and West Germany kept no statistics on it. In 1968, East Germany said that twenty thousand West Germans were crossing to East Germany every year. They were said not to be political, but this myth was disturbed in March 1968 when Wolfgang Kieling moved east. Kieling was a well-known German actor, famous in the United States for his portrayal of the East German villain in the 1966 Alfred Hitchcock movie

Torn >Curtain

starring Paul Newman. Kieling, who had fought for the Third Reich on the Russian front, was in Los Angeles at the time of the Watts race riots for the shooting of

Torn Curtain

and said he had been appalled by the United States. He said that he was leaving West Germany because of its backing of the United States, which, he said, was “the most dangerous enemy of humanity in the world today,” citing “crimes against the Negro and the people of Vietnam.”

In December 1966, Free University students fought in the streets with police for the first time. By then the American war in Vietnam had become one of the major issues around which the student movement organized. Using American demonstration techniques to protest against American policy, they quickly became the most noticeable student movement in Europe. But the students were also revolting against the materialism of West Germany and searching for a better way to achieve what East Germany had promised, a complete break with the Germany of the past. And while they were at it, they began demonstrating about tram fares and student living conditions.

On June 2, 1967, students gathered to protest Mayor Willy Brandt entertaining the shah of Iran. Once the guests were safely installed in the Opera House for a production of Mozart’s

The Magic Flute,

the police attacked the Free University students outside with violent fury. Students fled in panic, but twelve were so severely beaten that they had to be hospitalized, and one fleeing student, Benno Ohnesorg, was shot and killed. Ohnesorg had not been a militant, and this had been one of his first demonstrations. The policeman who shot him was quickly acquitted, whereas Fritz Teufel, leader of the protest group Commune I, faced a possible five-year sentence in a lengthy trial on the charge of “sedition.” The national student movement was built on anger over this killing, which was protested not only in Berlin but throughout Germany, demanding the creation of a new parliamentary group to oppose the German legislature.

On January 23, 1968, a right-wing Hamburg pastor, Helmuth Thielicke, found his church filled with students wanting to denounce his sermon. He called in West German troops to clear his church of the students, who were distributing pamphlets with a revised Lord’s Prayer: