2666 (33 page)

Authors: Roberto Bolaño

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary Collections, #Mystery & Detective, #Mexico, #Caribbean & Latin American, #Cold Cases (Criminal Investigation), #Crime, #Literary, #Young Women, #Missing Persons, #General, #Women

Amalfitano had

some

rather idiosyncratic

ideas

about jet lag.

They weren't consistent, so it might be an

exaggeration to call them ideas. They were feelings. Make-believe ideas. As if

he were looking out the window and forcing himself to see an extraterrestrial

landscape. He believed (or liked to think he believed) that when a person was

in Barcelona, the people living and present in Buenos Aires and Mexico City

didn't exist. The time difference only masked their nonexistence. And so if you

suddenly traveled to cities that, according to this theory, didn't exist or

hadn't yet had time to put themselves together, the result was the phenomenon

known as jet lag, which arose not from your exhaustion but from the exhaustion

of the people who would still have been asleep if you hadn't traveled. This was

something he'd probably read in some science fiction novel or story and that

he'd forgotten having read.

Anyway, these ideas or feelings or ramblings had their

satisfactions. They turned the pain of others into memories of one's own. They

turned pain, which is natural, enduring, and eternally triumphant, into

personal memory, which is human, brief, and eternally elusive. They turned a

brutal story of injustice and abuse, an incoherent howl with no beginning or

end, into a neatly structured story in which suicide was always held out as a

possibility. They turned flight into freedom, even if freedom meant no more

than the perpetuation of flight. They turned chaos into order, even if it was

at the cost of what is commonly known as sanity.

And although Amalfitano later found more information on the

life and works of Rafael Dieste at the University of Santa Teresa

library—information that confirmed what he had already guessed or what Don

Domingo Garcia-Sabell had insinuated in his prologue, titled "Enlightened

Intuition," which went so far as to quote Heidegger (

Es

gibt Zeit: there is time)

—on the afternoon when he'd

ranged over his humble and barren lands like a medieval squire, as his

daughter, like a medieval princess, finished applying her makeup in front of

the bathroom mirror, he could in no way remember why or where he'd bought the

book or how it had ended up packed and sent with other more familiar and

cherished volumes to this populous city that stood in defiance of the desert on

the border of Sonora and Arizona. And it was then, just then, as if it were the

pistol shot inaugurating a series of events that would build upon each other

with sometimes happy and sometimes disastrous consequences, Rosa left the house

and said she was going to the movies with a friend and asked if he had his keys

and Amalfitano said yes and he heard the door bang shut and then he heard his

daughter's footsteps along the path of uneven paving stones to the tiny wooden

gate that didn't even come up to her waist and then he heard his daughter's

footsteps on the sidewalk, heading off toward the bus stop, and then he heard

the engine of a car starting. And then Amalfitano walked into his devastated

front yard and looked up and down the street, craning his neck, and didn't see

any car or

tightly, which he was still holding in his left hand. And then he looked up at

the sky and saw the moon, too big and too wrinkled, although it wasn't night

yet. And then he returned to his ravaged backyard and for a few seconds he

stopped, looking left and right, ahead and behind, trying to see his shadow,

but although it was still daytime and the sun was still shining in the west,

toward

he couldn't see it. And then his eyes fell on the four rows of cord, each tied

at one end to a kind of miniature soccer goal, two posts perhaps six feet tall

planted in the ground, and a third post bolted horizontally across the top,

making them sturdier, the cords strung from this top bar to hooks fixed in the

side of the house. It was the clothesline, although the only things he saw

hanging on it were a shirt of

with ocher embroidery around the neck, and a pair of underpants and two towels,

still dripping. In the corner, in a brick hut, was the washing machine. For a

while he didn't move, breathing with his mouth open, leaning on the horizontal

bar of the clothesline. Then he went into the hut as if he were short of

oxygen, and from a plastic bag with the logo of the supermarket where he went

with his daughter to do the weekly shopping, he took out three clothespins,

which he persisted in calling

perritos,

as they were called in Chile,

and with them he clamped the book and hung it from one of the cords and then he

went back into the house, feeling much calmer.

The idea, of course, was Duchamp's.

All that exists, or remains, of Duchamp's stay in

ready-made. Though of course his whole life was a readymade, which was his way

of appeasing fate and at the same time sending out signals of distress. As

Calvin Tomkins writes: As a

wedding present for his sister Suzanne and his

close friend Jean Crotti, who were married in Paris on April 14, 1919, Duchamp

instructed the couple by letter to hang a geometry book by strings on the

balcony of their apartment so that the wind could "go through the book,

choose its own problems, turn and tear out the pages."

Clearly, then,

Duchamp wasn't just playing chess in

Aires

This

Unhappy

Readymade, as

he called it, might strike some newlyweds as an oddly

cheerless wedding gift, but Suzanne and Jean carried out Duchamp's instructions

in good spirit; they took a photograph of the open hook dangling in midair (the

only existing record of the work, which did not survive its exposure to the

elements), and Suzanne later painted a picture of it called

Le Readymade

malheureux de Marcel. As

Duchamp later told Cabanne, "It amused me to

bring the idea of happy and unhappy into readymades, and then the rain, the

wind, the pages flying, it was an amusing idea."

I take it back: all

Duchamp did while he was in

Aires

sick of all his play-science and left for

Duchamp

told one interviewer in later years that he had liked disparaging "the

seriousness of a book full of principles," and suggested to another that,

in its exposure to the weather, "the treatise seriously got the facts of

life."

That night, when

back from the movies, Amalfitano was watching television in the living room and

he told her he'd hung Dieste's book on the clothesline.

Amalfitano, I didn't hang it out because it got sprayed with the hose or

dropped in the water, I hung it there just because, to see how it survives the

assault of nature, to see how it survives this desert climate. I hope you

aren't going crazy, said

worry, said Amalfitano, in fact looking quite cheerful. I'm telling you so you

don't take it down. Just pretend the book doesn't exist. Fine,

The next day, as his students wrote, or as he himself was

talking, Amalfitano began to draw very simple geometric figures, a triangle, a

rectangle, and at each vertex he wrote whatever name came to him, dictated by

fate or lethargy or the immense boredom he felt thanks to his students and the

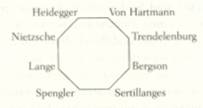

classes and the oppressive heat that had settled over the city. Like this:

Drawing 1

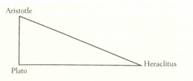

Or like this:

Drawing 2

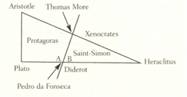

Or like this:

Drawing 3

When he returned to his cubicle he discovered the paper and

before he threw it in the trash he examined it for a few minutes. The only

possible explanation for Drawing 1 was boredom. Drawing 2 seemed an extension

of Drawing 1, but the names he had added struck him as insane. Socrates made

sense, there was a fleeting logic there, and Protagoras, too but why Thomas

More and Saint-Simon? Why Diderot, what was he doing there, and God in heaven,

why the Portuguese Jesuit Pedro da Fonseca, one of the thousands of

commentators on Aristotle, who by no amount of forceps wiggling could be taken

for anything but a very minor thinker? In contrast, there was a certain logic

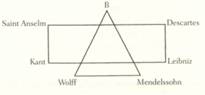

to Drawing 3, the logic of a teenage moron, or a teen bum in the desert, his

clothes in tatters, but clothes even so. All the names, it could be said, were

of philosophers who concerned themselves with ontological questions. The B that

appeared at the apex of the triangle superimposed on the rectangle could be God

or the existence of God as derived from his essence. Only then did Amalfitano

notice that an A and a B also appeared in Drawing 2, and he no longer had any

doubt that the heat, to which he was unaccustomed, was affecting his mind as he

taught his classes.

That night, however, after he had finished his dinner and

watched the TV news and talked on the phone to Professor Silvia Perez, who was

outraged at the way the

the crimes, Amalfitano found three more diagrams on his desk. It was clear he

had drawn them himself. In fact, he remembered doodling absentmindedly on a

blank sheet of paper as he thought other things. Drawing 1 (or Drawing 4) was

like this:

Drawing 4