2666 (36 page)

Authors: Roberto Bolaño

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary Collections, #Mystery & Detective, #Mexico, #Caribbean & Latin American, #Cold Cases (Criminal Investigation), #Crime, #Literary, #Young Women, #Missing Persons, #General, #Women

Despite everything, they had a pleasant day. Rosa and

Rafael swam in the pool and then joined Amalfitano and Professor Perez, who

were watching them from one of the tables. After that they all bought sodas and

went out to walk around. In some places the mountain dropped straight down, and

in the depths or on the cliff sides there were big gashes with

different-colored rock showing through, or rock that looked different colors in

the sun as it fled westward, lutites and andesites sandwiched between sandstone

formations, vertical outcrops of tuff and great trays of basaltic rock. Here

and there, a

mountains and then tiny valleys and more mountains, finally giving way to an

expanse veiled in haze, in mist, like a cloud cemetery, behind which were

Chihuahua and New Mexico and Texas. Sitting on rocks and surveying this view,

they ate in silence. Rosa and Rafael spoke only to exchange sandwiches.

Professor Perez seemed lost in her own thoughts. And Amalfitano felt tired and

overwhelmed by the landscape, a landscape that seemed best suited to the young

or the old, imbecilic or insensitive or evil and old who meant to impose

impossible tasks on themselves and others until they breathed their last.

That night Amalfitano was up until very late. The first

thing he did when he got home was go out into the backyard to see whether

Dieste's book was still there. On the ride home Professor Perez had tried to be

nice and start a conversation in which all four of them could participate, but

her son fell asleep as soon as they began the descent and soon afterward

wasn't long before Amalfitano followed his daughter's example. He dreamed of a

woman's voice, not Professor Perez's but a Frenchwoman's, talking to him about

signs and numbers and something Amalfitano didn't understand, something the

voice in the dream called "history broken down" or "history'

taken apart and put back together," although clearly the reassembled

history became something else, a scribble in the margin, a clever footnote, a

laugh slow to fade that leaped from an andesite rock to a rhyolite and then a

tufa, and from that collection of prehistoric rocks there arose a kind of

quicksilver, the American mirror, said the voice, the sad American mirror of

wealth and poverty and constant useless metamorphosis, the mirror that sails

and whose sails are pain. And then Amalfitano switched dreams and stopped

hearing voices, which must have meant he was sleeping deeply, and he dreamed he

was moving toward a woman, a woman who was only a pair of legs at the end of a

dark hallway and then he heard someone laugh at his snoring, Professor Perez's

son, and he thought: good. As they were driving into Santa Teresa on the

westbound highway, crowded at that time of day with dilapidated trucks and

small pickups on their way back from the city market or from cities in

only had he slept with his mouth open, but he had drooled on the collar of his

shirt. Good, he thought, excellent. When he looked in satisfaction at Professor

Perez, he detected an air of sadness about her. Out of sight of their

respective children, she lightly stroked Amalfitano's leg as he turned his head

and looked at a taco stand where a couple of policemen with guns on their hips

were drinking beer and talking and watching the red and black dusk, like a

thick chili whose last simmer was fading in the west. When they got home it was

dark but the shadow of Dieste's book hanging from the clothesline was clearer,

steadier, more reasonable, thought Amalfitano, than anything they'd seen on the

outskirts of Santa Teresa or in the city itself, images with no handhold,

images freighted with all the orphanhood in the world, fragments, fragments.

That night he waited, dreading the voice. He tried to

prepare for a class, but he soon realized it was a pointless task to prepare

for something he knew backward and forward. He thought that if he drew on the

blank piece of paper in front of him, the basic geometric figures would appear

again. So he drew a face and erased it and then immersed himself in the memory

of the obliterated face. He remembered (but fleetingly, as one members a

lightning bolt) Ramon Lull and his fantastic machine. Fantastic in its

uselessness. When he looked at the blank sheet again he had written the

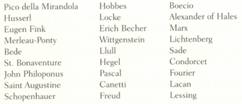

following names in three columns:

For a while, Amalfitano read and reread the names,

horizontally and vertically, from the center outward, from bottom to top,

skipping and at random, and then he laughed and thought that the whole thing

was a truism, in other words a proposition too obvious to formulate. Then he

drank a glass of tap water, water from the mountains of Sonora, and as he

waited for the water to make its way down his throat he stopped shaking, an

imperceptible shaking that only he could feel, and he began to think about the

Sierra Madre aquifers running toward the city in the middle of the endless

night, and he also thought about the aquifers rising from their hiding places

closer to Santa Teresa, and about the water that coated teeth with a smooth

ocher film. And when he'd drunk the whole glass of water he looked out the

window and saw the long shadow, the coffinlike shadow, cast by Dieste's book

hanging in the yard.

But the voice returned, and this time it asked him, begged

him, to be a man, not a queer. Queer? asked Amalfitano. Yes, queer, faggot,

cock-sucker, said the voice. Ho-mo-sex-u-al, said the voice. In the next breath

it asked him whether he happened to be one of those. One of what? asked

Amalfitano, terrified. A ho-mo-sex-u-al, said the voice. And before Amalfitano

could answer, it hastened to make clear that it was speaking figuratively, that

it had nothing against faggots or queers, in fact it felt boundless admiration

for certain poets who had professed such sexual leanings, not to mention

certain painters and government clerks. Government clerks? asked Amalfitano.

Yes, yes, yes,

said the voice young

government clerks with short life spans. Clerks who stained official documents

with senseless tears. Dead by their own hand. Then the voice was silent and

Amalfitano remained sitting in his office. Much later, maybe a quarter of an

hour later, maybe the next night, the voice said: let's say I'm your

grandfather, your father's father, and let's say that as your grandfather I can

ask you a personal question. You're free to answer or not, but I can ask the

question. My grandfather? said Amalfitano. Yes, your grandfather, said the

voice, you can call me

nono.

And my question for you is: are you a

queer, are you going to go running out of this room, are you a ho-mo-sex-u-al,

are you going to go wake up your

daughter? No, said Amalfitano. I'm

listening. Tell me what you have to say.

And the voice said: are you a queer? are you? and

Amalfitano said no and shook his head, too. I'm not going to run away. You

won't be seeing my back or the soles of my shoes. Assuming you see at all. And

the voice, said: see? as in

see?

to tell the truth, I can't. Not much,

anyway. It's enough work just keeping one foot in. Where? asked Amalfitano. At

your house, I suppose, said the voice. This is my house, said Amalfitano. Yes,

I realize, said the voice, now why don't we relax. I'm relaxed, said

Amalfitano, I'm here in my house. And he wondered: why is it telling me to

relax? And the voice said: I think this is the first day of what I hope will be

a long and mutually beneficial relationship. But if it's going to work out,

it's absolutely crucial that we stay calm. Calm is the one thing that will

never let us down. And Amalfitano said: everything else lets us down? And the

voice: yes, that's right, it's hard to admit, I mean it's hard to have to admit

it to you, but that's the honest-to-God truth. Ethics lets us down? The sense

of duty lets us down? Honesty lets us down? Curiosity lets us down? Love lets

us down? Bravery lets us down? Art lets us down? That's right, said the voice,

everything lets us down, everything. Or lets you down, which isn't the same

thing but for our purposes it might as well be, except calm, calm is the one

thing that never lets us down, though that's no guarantee of anything, I have

to tell you. You're wrong, said Amalfitano, bravery never lets us down. And

neither does our love for our children. Oh no? said the voice. No, said

Amalfitano, suddenly feeling calm.

And then, in a whisper, like everything he had said so far,

he asked whether calm was therefore the opposite of madness. And the voice

said: no, absolutely not, if you're worried that you've lost your mind, don't

worry, you haven't, all you're doing is having a casual conversation. So I

haven't lost my mind, said Amalfitano. No, absolutely not, said the voice. So

you're my grandfather, said Amalfitano. Call me pops, said the voice. So

everything lets us down, including curiosity and honesty and what we love best.

Yes, said the voice, but cheer up, it's fun in the end.

There is no friendship, said the voice, there is no love,

there is no epic, there is no lyric poetry that isn't the gurgle or chuckle of

egoists, the murmur of cheats, the babble of traitors, the burble of social

climbers, the warble of faggots. What is it you have against homosexuals?

whispered Amalfitano. Nothing, said the voice. I'm speaking figuratively, said

the voice. Are we in Santa Teresa? asked the voice. Is this city part of the

state of

A pretty significant part of it, in fact? Yes, said Amalfitano. Well, there you

go, said the voice. It's one thing to be a social climber, say, for example,

said Amalfitano, tugging at his hair as if in slow motion, and something very

different to be a faggot. I'm speaking figuratively, said the voice. I'm talking

so you understand me. I'm talking like I'm in the studio of a ho-mo-sex-u-al

painter, with you there behind me. I'm talking from a studio where the chaos is

just a mask or the faint stink of anesthesia. I'm talking from a studio with

the lights out, where the sinew of the will detaches itself from the rest of

the body the way the snake tongue detaches itself from the body and slithers

away, self-mutilated, amid the rubbish. I'm talking from the perspective of the

simple things in life. You teach philosophy?

said the voice. You teach Wittgenstein? said the voice. And have you

asked yourself whether your hand is a hand? said the voice. I've asked myself,

said Amalfitano. But now you have more important things to ask yourself, am I

right? said the voice. No, said Amalfitano. For example, why not go to a

nursery and buy seeds and plants and maybe even a little tree to plant in the

middle of your backyard? said the voice. Yes, said Amalfitano. I've thought

about my possible and conceivable yard and the plants and tools I need to buy.

And you've also thought about your daughter, said the voice, and about the

murders committed daily in this city, and about Baudelaire's faggoty (I'm

sorry) clouds, but you haven't thought seriously about whether your hand is

really a hand. That isn't true, said Amalfitano, I have thought about it, I

have. If you had thought about it, said the voice, you'd be dancing to the tune

of a different piper. And Amalfitano was silent and he felt that the silence

was a kind of eugenics. He looked at his watch. It was four in the morning. He

heard someone starting a car. The engine took a while to turn over. He got up

and went over to the window. The cars parked in front of the house were empty.

He looked behind him and then put his hand on the doorknob. The voice said: be

careful, but it said it as if it were very far away, at the bottom of a ravine

revealing glimpses of volcanic rock, rhyolites, andesites, streaks of silver

and gold, petrified puddles covered with tiny little eggs, while red-tailed

hawks soared above in the sky, which was purple like the skin of an Indian

woman beaten to death. Amalfitano went out onto the porch. To the left, some

thirty feet from his house, the lights of a black car came on and its engine

started. When it passed the yard the driver leaned out and looked at Amalfitano

without stopping. He was a fat man with very black hair, dressed in a cheap

suit with no tie. When he was gone, Amalfitano came back into the house. I

didn't like the looks of him, said the voice the minute Amalfitano was through

the door. And then: you'll have to be careful, my friend, things here seem to

be coming to a head.

So who are you and how did you get here? asked Amalfitano.

There's no point going into it, said the voice. No point? asked Amalfitano,

laughing in a whisper, like a fly. There's no point, said the voice. Can I ask

you a question? said Amalfitano. Go ahead, said the voice. Are you really the

ghost of my grandfather? The things you come up with, said the voice. Of course

not, I'm the spirit of your father. Your grandfather's spirit doesn't remember

you anymore. But I'm your father and I'll never forget you. Do you understand?

Yes, said Amalfitano. Do you understand that you have nothing to fear from me?

Yes, said Amalfitano. Do something useful, then check that all the doors and

windows are shut tight and go to sleep. Something useful like what? asked

Amalfitano. For example, wash the dishes, said the voice. And Amalfitano lit a

cigarette and began to do what the voice had suggested. You wash and I'll talk,

said the voice. All is calm, said the voice. There's no bad blood between us.

The headache, if you have a headache, will go away soon, and so will the

buzzing in your ears, the racing pulse, the rapid heartbeat. You'll relax, you'll

think some and relax, said the voice, while you do something useful for your

daughter and yourself. Understood, whispered Amalfitano. Good, said the voice,

this is like an endoscopy, but painless. Got it, whispered Amalfitano. And he

scrubbed the plates and the pot with the remains of pasta and tomato sauce and

the forks and the glasses and the stove and the table where they'd eaten,

smoking one cigarette after another and also taking occasional gulps of water

straight from the faucet. And at five in the morning he took the dirty clothes

out of the bathroom hamper and went out into the backyard and put the clothes

in the washing machine and pushed the button for a normal wash and looked at

Dieste's book hanging motionless and then he went back into the living room and

his eyes, like the eyes of an addict, sought out something else to clean or

tidy or wash, but he couldn't find anything and he sat down, whispering yes or

no or I don't remember or maybe. Everything is fine, said the voice. It's all a

question of getting used to it. Without making a fuss. Without sweating and

flailing around.