2666 (34 page)

Authors: Roberto Bolaño

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary Collections, #Mystery & Detective, #Mexico, #Caribbean & Latin American, #Cold Cases (Criminal Investigation), #Crime, #Literary, #Young Women, #Missing Persons, #General, #Women

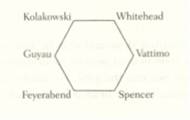

Drawing 5

193

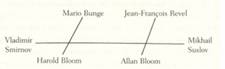

And Drawing 6

Drawing 4 was odd. Trendelenburg—it had been years since he

thought about Trendelenburg. Adolf Trendelenburg. Why now, precisely, and why

in the company of Bergson and Heidegger and Nietzsche and Spengler? Drawing 5

was even odder. The appearance of Kolakowski and Vattimo. The presence of

Whitehead, forgotten until now. But especially the unexpected materialization

of poor Guyau, Jean-Marie Guyau, dead at thirty-four in 1888, called the French

Nietzsche by some jokers, with no more than ten disciples in the whole world,

although really there were only six, and Amalfitano knew this because in

Barcelona he had met the only Spanish Guyautist, a professor from Gerona, shy

and a zealot in his own way, whose great quest was to find a text (it might

have been a poem or a philosophical piece or an article, he wasn't sure) that

Guyau had written in English and published in a San Francisco newspaper

sometime around 1886—1887. Finally, Drawing 6 was the oddest of all (and the

least "philosophical"). What said it all was the appearance at

opposite ends of the horizontal axis of Vladimir Smirnov, who disappeared in

Stalin's concentration camps in 1938 (not to be confused with Ivan Nikitich

Smirnov, executed by the Stalinists in 1936 after the first Moscow show trial),

and Suslov, party ideologue, prepared to countenance any atrocity or crime. But

the intersection of the horizontal by two slanted lines, reading Bunge and

Revel above and Harold Bloom and Allan Bloom below, was something like a joke.

And yet it was a joke Amalfitano didn't understand, especially the appearance

of the two Blooms. There had to be something funny about it, but whatever it

might be, he couldn't put his finger on it, no matter how he tried.

That night, as his daughter slept, and after he listened to

the last news broadcast on Santa Teresa's most popular radio station, Voice of

the Border, Amalfitano went out into the yard. He smoked a cigarette, staring

into the deserted street, then he headed for the back, moving hesitantly, if he

feared stepping in a hole or was afraid of the reigning darkness. Dieste's book

was still hanging with the clothes Rosa had washed that day, clothes that

seemed to be made of cement or some very heavy material, because they didn't

move at all, while the fitful breeze swung the book back and forth, as if it

were grudgingly rocking it or trying to detach it from the clothespins holding

it to the line. Amalfitano felt the breeze on his face. He was sweating and the

irregular gusts of air dried the little drops of perspiration and occluded his

soul. As if I were in Trendelenburg's study, he thought, as if I were following

in Whitehead's footsteps along the edge of a canal, as if I were approaching

Guyau's sickbed and asking him for advice. What would his response have been? Be

happy. Live in the moment. Be good. Or rather: Who are you? What are you doing

here? Go away.

Help.

The next day, searching in the university library, he found

more information on Dieste. Born in Rianxo, La Corufia, in 1899. Begins writing

in Galician, although later he switches to Castilian or writes in both. Man of

the theater. Anti-Fascist during the Civil War. After his side's defeat he goes

into exile, ending up in

where he publishes

Viaje, duelo y perdition: tragedia, humorada y comedia,

in

1945, a book made up of three previously published works. Poet. Essayist. In

1958 (Amalfitano is seven), he publishes the aforementioned

Nuevo tratado

As

a short story writer, his most important work is

Historia e invenciones de

Felix Muriel

(1943). Returns to

returns to

Dies in Santiago de Compostela in 1981.

What's the experiment? asked

What experiment? asked Amalfitano. With the hanging book, said

word, said Amalfitano. Why is it there? asked

It occurred to me all of a sudden, said Amalfitano, it's a Duchamp idea,

leaving a geometry book hanging exposed to the elements to see if it learns

something about real life. You're going to destroy it, said

Not me, said Amalfitano, nature. You're getting crazier every day, you know,

said

you do a thing like that to a book, said

It isn't mine, said Amalfitano. It doesn't matter,

but I really don't have the sense it belongs to me, and anyway I'm almost sure

I'm not doing it any harm. Well, pretend it's mine and take it down, said

neighbors: who top their walls with broken glass? They don't even know we

exist,

said Amalfitano, and they're a

thousand times crazier than me. No, not them, said Rosa, the other ones, the

ones who can see exactly what's going on in our yard. Have any of them bothered

you? asked Amalfitano. No, said

it's not a problem, said Amalfitano, it's silly to worry' about it when much

worse things are happening in this city than a book

being hung from a cord. Two wrongs don't make

a right, said

the book alone, pretend it doesn't exist, forget about it, said Amalfitano,

you've never been interested in geometry.

In the mornings, before he left for the university,

Amalfitano would go out the back door to watch the book while he finished his

coffee. No doubt about it: it had been printed on good paper and the binding

was stoically withstanding nature's onslaught. Rafael Dieste's old friends had

chosen good materials for their tribute, a tribute that amounted to an early farewell

from a circle of learned old men (or old men with a patina of learning) to

another learned old man. In any case, nature in northwestern

particularly in his desolate yard, thought Amalfitano, was in short supply. One

morning, as he was waiting for the bus to the university, he made firm plans to

plant grass or a lawn, and also to buy a little tree in some store that sold

that kind of thing, and plant flowers along the fence. Another morning he

thought that any work he did to make the yard nicer would ultimately be

pointless, since he didn't plan to stay long in Santa Teresa. I have to go back

now, he said to himself, but where? And then he asked himself: what made me

come here? Why did I bring my daughter to this cursed city? Because it was one

of the few hellholes in the world I hadn't seen yet? Because I really just want

to die? And then he looked at Dieste's book, the

Testamento geometrico,

hanging

impassively from the line, held there by two clothespins, and he felt the urge

to take it down and wipe off the ocher dust that had begun to cling to it here

and there, but he didn't dare.

Sometimes, after he came home from the

remembered his father, who followed boxing. Amalfitano's father used to say

that all Chileans were faggots. Amalfitano, who was ten, said: but Dad, it's

really the Italians who are faggots, just look at World War II. Amalfitano's

father gave his son a very serious look when he heard him say that. His own

father, Amalfitano's grandfather, was born in

Italian than Chilean. But anyway, he liked to talk about boxing, or rather he

liked to talk about fights that he'd only read about in the usual articles in

boxing magazines or the sports page. So he would talk about the Loayza

brothers, Mario and Ruben, nephews of El Tani, and about Godfrey Stevens, a

stately faggot with no punch, and about Humberto Loayza, also a nephew of El

Tani, who had a good punch but no stamina, about Arturo Godoy, a wily fighter

and martyr, about Luis Vicentini, a powerfully built Italian from Chillan who

was defeated by the sad fate of being born in Chile, and about Estanislao

Loayza, El Tani, who was robbed of the world title in the United States in the

most ridiculous way, when the referee stepped on his foot in the first round

and El Tani fractured his ankle. Can you imagine? Amalfitano's father asked. I

can't imagine, Amalfitano said. Let's give it a try, said Amalfitano's father,

shadowbox around me and I'll step on your foot. I'd rather not, said

Amalfitano. You can trust me, you'll be fine, said Amalfitano's father. Some

other time, said Amalfitano. It has to be now, said his father. Then Amalfitano

put up his fists and moved around his father with surprising agility, throwing

a few jabs with his left and hooks with his right, and suddenly his father

moved in and stepped on his foot and that was the end of it, Amalfitano stood

still or tried to go in for a clinch or pulled away, but in no way fractured

his ankle. I think the referee did it on purpose, said Amalfitano's father. You

can't fuck up somebody's ankle by stomping on his foot. Then came the rant:

Chilean boxers are all faggots, all the people in this shitty country are

faggots, every one of them, happy to be cheated, happy to be bought, happy to

pull down their pants the minute someone asks them to take off their watches.

It was at this point that Amalfitano, who at ten read history Magazines,

especially military history magazines, not sports magazines, answered that the

Italians had already claimed that role, all the way back World War II. His

father was silent then, looking at his son with frank admiration and pride, as

if asking himself where the hell the kid had come from, and then he was silent

for a while longer and afterward he said in a low voice, as if telling a

secret, that Italians were brave individually. In large numbers, he admitted,

they were hopeless. And this, he explained, was precisely what gave a person

hope.

By which you might guess, thought Amalfitano, as he went

out the front door and paused on the porch with his whiskey and then looked out

into the street where a few cars were parked, cars that had been left there for

hours and smelled, or so it seemed to him, of scrap metal and blood, before he

turned and headed around the side of the house to the backyard where the

Testamento

geometrico

was waiting for him in the stillness and the dark, by which you

might guess that he himself, deep down, very deep down, was still a hopeful

person, since he was Italian by blood, as well as an individualist and a

civilized person. And it was even possible that he wasn't a coward. Although he

didn't like boxing. But then Dieste's book fluttered and the black handkerchief

of the breeze dried the sweat beading on his forehead and Amalfitano closed his

eyes and tried to conjure up any image of his father, in vain. When he went

back inside, not through the back door but through the front door, he peered

over the gate and looked both ways down the street. Some nights he had the

feeling he was being spied on.

In the mornings, when Amalfitano came into the kitchen and

left his coffee cup in the sink after his obligatory visit to Dieste's book,

although sometimes, if Amalfitano came in sooner than usual or put off going

into the backyard, he would say goodbye, remind her to take care of herself, or

give her a kiss. One morning he managed only to say goodbye, then he sat at the

table looking out the window at the clothesline. The

Testamento geometrico

was

moving imperceptibly. Suddenly, it stopped. The birds that had been singing in

the neighboring yards were quiet. Everything was plunged into complete silence

for an instant. Amalfitano thought he heard the sound of the gate and his

daughter's footsteps receding. Then he heard a car start. That night, as

Professor Perez and confessed that he was turning into a nervous wreck.

Professor Perez soothed him, told him not to worry so much, all you had to do

was be careful, there was no point giving in to paranoia. She reminded him that

the victims were usually kidnapped in other parts of the city. Amalfitano

listened to her talk and all of a sudden laughed. He told her his nerves were

in tatters. Professor Perez didn't get the joke. Nobody gets anything here,

thought Amalfitano angrily. Then Professor Perez tried to convince him to come

out that weekend, with Rosa and Professor Perez's son. Where to, asked

Amalfitano, almost inaudibly. We could go eat at a

merendero

ten miles

out of the city, she said, a very nice place, with a pool for the kids and lots

of outdoor tables in the shade with a view of the slopes of a quartz mountain,

a silver mountain with black streaks. At the top of the mountain there was a

chapel built of black adobe. The inside was dark, except for the light that

came in through a kind of skylight, and the walls were covered in ex-votos

written by travelers and Indians in the nineteenth century who had risked the

pass between