A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (44 page)

Read A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination Online

Authors: Philip Shenon

Two weeks later, a Dallas psychiatrist, Robert Stubblefield, visited Ruby at the request of the judge in Ruby’s trial, and he agreed that Ruby was severely mentally ill and in need of hospital treatment. Ruby readily acknowledged to Stubblefield that he had killed Oswald, and that he had done it—as he had claimed from the beginning—to help Jacqueline Kennedy. “I killed Oswald so Mrs. Kennedy would not have to come to Dallas and testify,” he said. “I loved and admired President Kennedy.”

Ruby insisted, again, that he had acted alone in murdering Oswald, Stubblefield reported. His enemies “think I knew Oswald, that it was a part of some plot,” he told the psychiatrist. “It’s not true. I want to take a polygraph test to prove that I did not know Oswald, that I was not involved in killing President Kennedy. After that, I don’t care what happens to me.”

31

THE STATE DEPARTMENT

WASHINGTON, DC

TUESDAY, APRIL 7, 1964

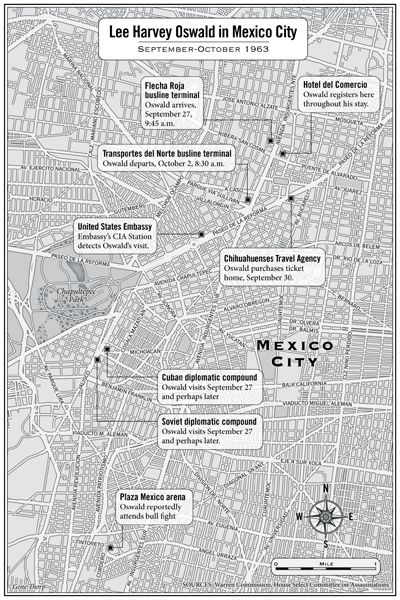

In the final days of planning for their trip to Mexico City, David Slawson and William Coleman decided they had no higher priority there than to arrange an interview with Silvia Duran. Her importance to the investigation had only grown in the weeks since January, when the two lawyers heard her name for the first time. “Duran could be my most important witness,” Slawson told himself. “Just imagine what she might know.” At the request of the CIA, Duran was going to be cited, by name, as an essential source for information in the commission’s final report about Oswald’s visit to Mexico. The CIA was eager not to give away any details of its elaborate photo-surveillance and wiretapping operations in Mexico City. Instead, the agency wanted the commission, whenever possible, to attribute information only to Duran if her testimony overlapped with what the CIA had also learned through its spycraft. If the CIA had its way, what Duran disclosed to her Mexican interrogators—or, at least, what the Mexicans claimed she had disclosed—would be the only publicly available record of many of Oswald’s activities in Mexico.

The day before their departure, Slawson and Coleman were invited to the State Department for a briefing by Assistant Secretary of State Thomas Mann, the former American ambassador in Mexico City; he had left Mexico four months earlier. Slawson and Coleman were ushered through the lobby, past the rows of brightly colored foreign flags that decorated the hallways, and into Mann’s offices. He invited the two lawyers to take a seat, and he apologized for the unpacked boxes; he was still settling back into Washington, and it had been a busy time. In his new job, he said, he oversaw all Latin American affairs for the State Department and, given his growing friendship with President Johnson, a fellow Texan, he was a frequent visitor at the White House.

Since Slawson had finally been given a chance only two weeks earlier to read through all of Mann’s top secret cable traffic from Mexico from late November, he knew just how valuable Mann’s perspective might be on the question of a foreign conspiracy. So Slawson and Coleman asked the question directly: Was Mann still convinced that the Kennedy assassination was a Cuban plot?

He was, he said, even if he still could not prove it. Mann felt “in my guts” that Castro was “the kind of dictator who might have carried out this kind of ruthless action, either through some hope of gaining from it or simply as revenge.” The fact that Oswald had visited both the Cuban and the Russian embassies before the assassination “seemed sufficient … to raise the gravest concerns” that Oswald had acted at the direction of the Cubans, possibly with the tacit agreement of their Soviet backers. Mann said his suspicion of a Communist plot had only grown stronger after he learned about the Nicaraguan spy in Mexico City who claimed to have seen Oswald being paid $6,500 in the Cuban embassy, and after learning about the intercepted phone call between Cuba’s president and the country’s ambassador to Mexico, in which the two Cubans talked about the rumors that Oswald had been paid off.

Mann excused himself, saying he had to leave for another meeting, although he invited Slawson and Coleman to consult with him again after their trip. As he shook their hands good-bye, Mann turned to Slawson and asked if the commission felt he had overreacted to the evidence. Had he been “unduly rash” in suspecting a Cuban conspiracy in the assassination? No, Slawson replied. Although the evidence increasingly pointed away from any foreign involvement in Kennedy’s death, the commission’s investigators had “found nothing in what the ambassador had done to be unjustified.”

In the days before the trip, Slawson received a separate briefing from the CIA on what to expect in Mexico City. “The CIA told me that Mexico City was a spy headquarters, so to speak, for lots of countries—like Istanbul used to be in detective thrillers. The spies always met in Istanbul.” In the early 1960s, Mexico City was a capital of Cold War espionage, and Slawson was excited to see it for himself.

*

On Wednesday, April 8, Slawson and Coleman, accompanied by Howard Willens, boarded an Eastern Airlines plane at Dulles Airport and flew to Mexico City, arriving that evening at six. They were met at the airport by Clark Anderson, the FBI’s legal attaché in Mexico. Because of the color of his skin, Coleman was used to being harassed when he traveled, both at home and abroad, and an immigration officer tried to block his entry to the country, questioning whether he had proper vaccination papers. He was waved through after an Eastern Airlines manager noted “something to the effect that Mr. Coleman was a representative of the Warren Commission,” Slawson wrote later.

Coleman was nervous throughout the visit, fearing his life was in danger because of the secrets he knew from the commission. He had known threats of violence in the past—they were common for anyone prominent in the civil rights movement—but it was more frightening to face that danger in the streets of a foreign capital. If there had been a conspiracy to kill Kennedy, it seemed possible to Coleman that some of Oswald’s coconspirators were still in Mexico, eager to kidnap him and force him to share what he knew. “If the Mexicans were involved in the conspiracy, maybe they would kill me,” he worried. That first night, he had trouble sleeping in his room at the Continental Hilton Hotel, especially after he heard a mysterious rustling.

“About three o’clock in the morning, I could hear scratching at the windows, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, somebody’s come to kill me,’” Coleman remembered. “I’d better get the hell out of here.… I was scared as hell.”

The next day, he asked a CIA official standing outside the hotel if there had been any threat. No, the CIA man assured him. “Don’t worry, we watched you all night.”

That morning, the commission’s delegation arrived at the sprawling American embassy compound on Paseo de la Reforma, where they were introduced to Winston Scott, the CIA’s station chief, and to the newly arrived ambassador, Fulton Freeman, who had been in the city only two days. At a meeting with Scott and the ambassador, Coleman explained that the commission lawyers planned to meet with Mexican officials and hoped to conduct depositions, especially with Duran. Freeman had been briefed enough to know how important Duran was, and how delicate a subject she was for the Mexican government. The ambassador said that “seeing Silvia Duran would be a highly sensitive matter and that it should be discussed fully” before anyone approached her, Slawson recalled. Freeman said he would give his approval for an interview with Duran “so long as we saw her in the American Embassy and made clear to her that her appearance was entirely voluntary.”

Slawson and Coleman met separately with Anderson and his FBI colleagues in the embassy. Although Anderson would concede years later how limited the bureau’s investigation in Mexico City had been, he left his visitors that day with the impression that the FBI had been aggressive in following up on leads about Oswald. Anderson gave off “a very good impression of competence,” Slawson wrote later.

The commission lawyers asked Anderson what he made of Duran. He said he believed she was a “devout Communist” who, while married and the mother of a young child, had a reputation for a scandalous private life. As Anderson put it, she was a “Mexican pepperpot” and notably “sexy.” He agreed with the ambassador that a request to interview her would be a “touchy point” for the Mexican government, although he said he would try to help. He had good news for them about Duran—just that morning, the FBI had finally obtained a copy of her signed statement to her Mexican interrogators about Oswald, a document the commission had previously known nothing about. Slawson and Coleman said they wanted a copy as soon as possible.

*

The two lawyers spent much of the afternoon with Scott, and they found that the CIA station chief lived up to his reputation for unusual intelligence. He impressed Slawson with his milky, southern-bred charm, and the two men bonded over the discovery of their shared love of math and science. Both talked about how they had almost ended up in academia—Slawson trained in physics at Princeton, Scott in mathematics at the University of Michigan. “It was common ground,” Slawson remembered. “There was something simpatico between us.” (Since Scott operated undercover for the CIA, identified officially to the Mexican government as an employee of the State Department, Slawson removed all references to his real name in his later reports about Mexico City, replacing it with the single letter “A.”)

Slawson and Coleman were impressed when Scott took them downstairs in the embassy to a soundproof safe room for his initial briefing about Oswald. “It was way down in the basement—it may have even been in a subbasement,” Slawson remembered. “Everything that was told to us in the safe room or shown to us was considered top, top secret.” During the briefing, which was also attended by the embassy’s number-two CIA officer, Alan White, Scott turned on a small radio; he said it would muffle the sound of their conversation, a precaution in case someone was trying to listen in. “It was all very cloak-and-dagger,” Slawson said.

As he began the briefing, Scott went out of his way to convince the visiting lawyers that he and the agency intended to cooperate fully with the commission and that he intended to hold nothing back, even at some risk to the CIA. He said he understood that the lawyers had “been cleared for Top Secret and that we would not disclose beyond the confines of the commission and its immediate staff the information we obtained through him without first clearing it with his superiors in Washington,” Slawson recalled. “We agreed to this.”

Scott then described, in detail, how Oswald had been tracked in Mexico using some of the CIA’s most sophisticated surveillance technology, including wiretaps of almost all phones at the Soviet and Cuban embassies, as well as with the banks of hidden cameras mounted outside the two embassies. The exhaustive surveillance had begun, he said, within hours of Oswald’s first appearance at the Cuban embassy. He then described how the Mexico City station had responded to the assassination, immediately compiling dossiers on “Oswald and everyone else throughout Mexico” who might have had contact with the alleged assassin. He pulled out the transcripts of what he said were Oswald’s phone calls to the Cuban and Soviet embassies. The lawyers raised Duran’s name, and Scott acknowledged that she had been of “substantial interest to the CIA” long before the Kennedy assassination because of her affair with a senior Cuban diplomat, Carlos Lechuga, while he was Cuba’s ambassador in Mexico; Lechuga had gone on to become his nation’s ambassador to the United Nations in New York. After the assassination, Scott said, the CIA had worked closely with Mexican authorities, “especially on the Duran interrogations.”

Slawson was impressed by how comprehensive this briefing was. But as he listened to Scott, the young lawyer also found himself alarmed to realize how much of this information he had never heard before. Scott offered details about Oswald’s visit to Mexico that his colleagues back at CIA headquarters had never passed on to the commission, despite the agency’s recent effort to reassure the investigation that nothing was being held back. Other information that had been previously shared by the CIA was filled with “distortions and omissions,” Slawson now knew. He and Coleman had brought along their own chronology of Oswald’s activities in Mexico, intending to show it to Scott for his comments. “But once we saw how badly distorted our information was, we realized that this would be useless.”

Slawson asked Scott why, given the elaborate photo-surveillance system, the commission had not yet been provided with photos of Oswald. Unfortunately, Scott replied, there were no photos. “Photographic coverage was limited by and large to the daylight weekday hours, because of lack of funds and because there were no adequate technical means for taking photographs at night from a long distance without artificial light,” he told the lawyers. The answer was clearly evasive, Scott’s colleagues would say later. Oswald was not known to have visited the embassies at night, and the Mexico City station was one of the best-funded and -equipped in the CIA. But Slawson and Coleman accepted Scott’s explanation, if only because they had no good way of challenging it. Slawson remembered being surprised to learn that there were no photos. “I remember being puzzled, I guess, but I was too innocent to think they would deliberately hide stuff,” Slawson said later. “I think I was naive.”