A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (23 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

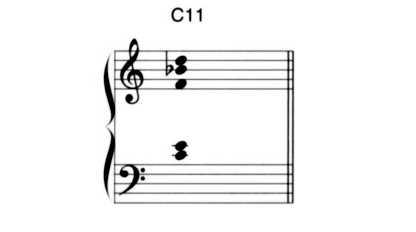

Figure 6-12. An assortment of 9th, 11th, and 13th chord voicings. Using these voicings as a starting point, it's a useful exercise to try adding, omitting, octave-transposing, or altering various chord tones to find other voicings that are pleasing to your ear.

Figure 6-13. When the first chord in Figure 6-6 is revoiced a bit, it becomes surprisingly pleasant. Perhaps this is because the clash between the major 3rd and the natural 11th is less disturbing to the ear when they're in the same octave.

Placing the augmented 9th in a lower octave than the major 3rd is probably a bad idea, because the ear will interpret the 9th as a minor 3rd. The augmented 9th can be played in the same octave as the major 3rd, however, producing a half-step major-minor dissonance.

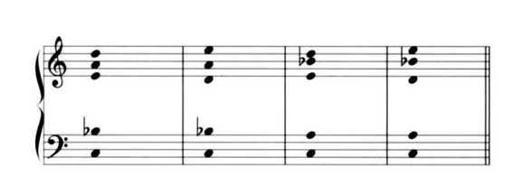

Figure 6-14. Normally, the higher functions of a chord are placed higher in the voicing, but this principle can sometimes be violated with good results. The first C13 chord is in a "normal" configuration, with the 13th and 9th at the top. In the second chord, the 3rd and 9th have switched places. In the third chord, the 13th and 7th have switched places. In the last chord, both swaps have taken place. The third and fourth voicings are darker and more mysterious, but not bad at all. Try playing these voicings on the keyboard a few times, alternating them until you can hear the sounds as interchangeable.

Fourth, as more notes are added to the voicing, the potential for harmonic confusion grows. This can be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on the musical context. To begin with, let's note that most extended chords contain all of the notes of one or more triads other than the triad built on the root of the chord. Look, for example, at the chords in Figure 6-12c, 6-12e, and 6-12h. In each case, the notes in the treble clef form a triad - A minor, G major, and D major, respectively. These triads clash with the underlying C tonality, but in an interesting way.

If we swap the right-hand notes in Figure 6-12e into the left hand and viceversa, we get the awkward chord in Figure 6-15. What is this chord, harmonically speaking? It's hard to say. It has the same notes as the Cmaj9 in Figure 6-12e, but the sound of the G triad now dominates the voicing. The ear simply doesn't interpret this voicing as a C chord. Yet it doesn't sound functionally like a G chord either, because of the prominent E-C interval. At best, we could call it a bitonal G/C chord. This is not to say that the voicing is useless - but if you play it when the chord chart calls for a Cmaj9, your fellow musicians will give you a few funny looks.

Figure 6-15. This chord was created by swapping the left- and right-hand notes in the chord in Figure 6-12e. Although the notes are the same, moving the G major triad to the bottom gives us a voicing that is no longer identifiable as a C major chord. Its harmonic identity is not at all clear.

Figure 6-16. This chord was created by swapping the left- and right-hand notes in the chord in Figure 6-12g. The original voicing was bitingly thick, but could still be perceived by the ear as a C dominant. When the 13th, sharp 9th, and flat 5th are dropped down to a lower octave, the result is harmonic sludge.

Still not convinced? Try swapping hands with the voicing in Figure 6-12g, moving the diminished 7th component down to the left hand, as shown in Figure 6-16. It's a harmonic train wreck.

When choosing the notes for a chord voicing, then, you need to be sensitive to internal combinations of notes (usually triads, tritones, or dissonant minor 2nds and minor 9ths) that may convey harmonic ideas you don't want. As long as you're following this principle, however, harmonic clashes can be a good thing. Consider the right-hand voicing in Figure 6-17. It's clearly a C dominant chord, at least to my ears. The A major triad (enharmonically spelled with a D6) is masked by the B6 and E6, and doesn't create much ambiguity. The ear focuses mainly on the clashing half-steps.

Figure 6-17. Dissonance doesn't always create harmonic ambiguity. If you don't play the C root in the left hand, the upper notes are not readily identifiable as a C voicing, but they don't imply any other root either. Note that the split accidental notes (E6 and Eq) are intended to be played at the same time. They're offset purely because of the limitations of our notation system.

AMBIGUOUS VOICINGS

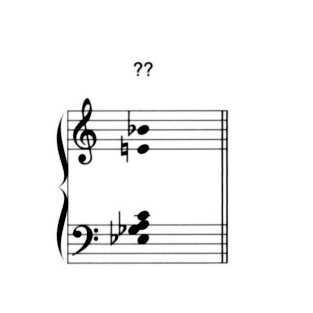

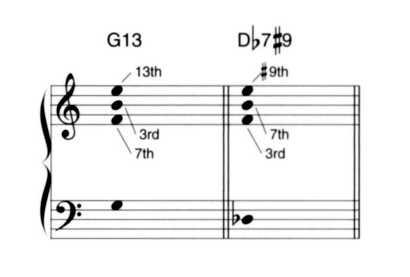

In spite of the potential for confusion discussed above, harmonic ambiguity is not, in itself, a bad thing. On the contrary. Take a look at the right-hand voicing in Figure 6-18. This is an important voicing, one you'll hear often - but what is it? If we play a G in the root, it's clearly a G 13 chord (though there's no 9th). If we play a D6 root, on the other hand, the voicing is just as clearly a D67#9. Figure 6-19 makes this clear.

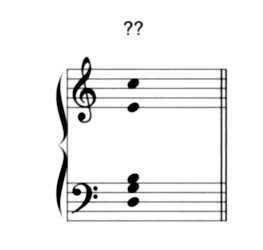

Figure 6-18. Can you identify this voicing? Hint #1: It doesn't contain a root or a 5th. Hint #2: The tritone between 8 and F indicates that you're looking for a dominant-type chord.

Figure 6-19. The voicing in Figure 6-18 can function either as a G 13 or as a D67#9. (In the latter case, the 7th of the chord is spelled enharmonically as a eq rather than as a C6, which would technically be the correct spelling.)

In Chapter Five, we introduced the idea of the tritone substitution, in which a dominant-type chord is replaced with a different dominant-type chord whose root is a tritone away from the original root. To review, please glance back at Figures 5-26 and 5-27. In Figure 6-19, we've stacked a perfect 4th above the tritone, and then used tritone substitution to replace a G 13 chord with a D67#9. Yet if we play a rootless voicing, as a pianist or keyboard player would typically do, leaving the root for the bass player, the two chord voicings are identical.

This fact is worth exploring further. In Figure 6-20, a couple of variations on the voicing from Figure 6-18 are shown. In each case, a note has one identity in the G chord and a separate identity in the D6 chord, yet none of the notes creates any undesirable harmonic ambiguities in either chord.

The world of jazz harmony is full of ambiguous chord voicings that work well. Another simple example is shown in Figure 6-21. Are these notes part of a C9 chord? A B6maj7? Or are they extracted from a Gm9? The answer is, "All of the above" They could be part of an F#7#9#5, for that matter. Take a look at how these notes are used in the riff in Figure 6-22. The A, 136, and D don't change when the root moves from G to C. They work in both chords. (There's a bit more movement in measure 2. I've added this measure purely to show how such chords might appear in an arrangement.)