A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (26 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

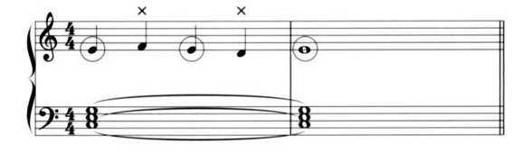

Figure 6-37. Slipping an augmented 4th (left) or a major 3rd (right) into the middle of a fourth-chord can produce some useful voicings.

What this means is that if you want a fourth-chord to be perceived as a fourth-chord, or a cluster-chord to be perceived as a cluster-chord, your options for revoicing it are limited.

Fourth-chords are a limited resource, but they're well worth experimenting with. For instance, rather than alter a single note, as in Figure 6-35, we can insert an augmented 4th or a major 3rd into the middle of the stack, and then go on adding perfect 4ths above it. A couple of possibilities are shown in Figure 6-37.

BITONAL CHORDS

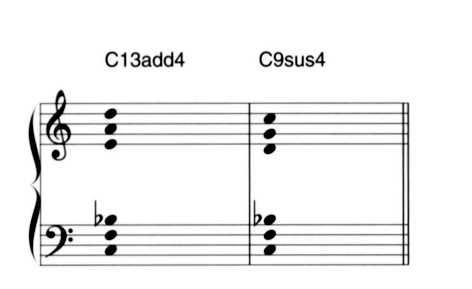

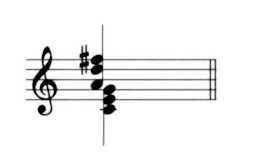

What is the chord shown in Figure 6-38? One way of analyzing it is as a Cmaj 13# 11 with no 7th. If we look at it this way, the A is the 13th of the chord, the F# the #11, and the D the 9th. But this analysis seems needlessly academic. What we're really hearing are a C major triad and a D major triad played at the same time - two separate chords, each with its own root, 3rd, and 5th. Since each triad has its own tonal center (the root), harmonic structures built in this manner are called bitonal. Bitonality is not restricted to combining triads; bitonal writing containing 7ths, 9ths, and other notes is quite practical.

The use of bitonality became important in classical music in the early 20th century, and it remains an important harmonic resource for many classical composers. Whole passages are sometimes written in which one instrument or group of instruments plays in one key, while a different instrument or group plays in another key. To an unsophisticated listener, the results can be jarringly discordant, but as you gain familiarity with bitonal sonorities, you may find it possible to tease out the various harmonic strands and thereby make a lot more sense of the music.

Figure 6-38. This bitonal chord consists of independent C major and D major triads.

Consider, for example, the bitonal riff in Figure 6-39. At any given moment, the intervals between the left and right hands are likely to be quite dissonant - the C and C# played together on the first beat, for instance. But if you play this passage a couple of times, its inner logic should become easier to hear. Each hand is playing a simple V-I progression, but the right hand is playing in the key of B, while the left hand plays in the key of F.

Figure 6-39. In this bitonal passage, the two lines are in different keys. (Note the key signatures.) The right hand plays a V-I progression in the key of e, while the left hand also plays a V-I progression with the same harmonic rhythm, but in the key of F.

This passage illustrates an important aspect of bitonalism: It's sometimes used in multi-part writing in which various instruments play passages that are not, considered in isolation, bitonal. The bitonalism is a result of the combination of parts. The parts may not be notated with separate key signatures, however. Accidentals are normally employed. Also, there's no requirement that the various parts play conventional progressions, such as the V-I progression shown in Figure 6-39. The term "bitonal" refers simply to a vertical sonority that employs two (or more) independent triads or extended chords.

Bitonal writing can become far more sophisticated than this. I'd encourage you to experiment with it on your own, and to listen to how bitonalism is used by composers like Aaron Copland.

You might expect that bitonality would be too weird or abstract to find a home in pop music - but in fact, bitonal chords are sometimes used in modern R&B. A chord chart that calls for ordinary 7th or 9th chords can sound too sweet or lacking in attitude. To create an edgier, more interesting sound, two chording instruments may play different chords, or the bass may imply one progression while a chording instrument plays a different progression.

There's no easy way to use chord symbols in bitonal writing. As noted in Chapter Five, a symbol like B6/C usually indicates a B6 major triad over a C bass note, not a B6 major triad over a complete C major triad. If the element of the symbol that follows the slash mark contains a 7 or some other indication that a full chord is intended (for instance, B6m9/C7), then it's clear that a complete bitonal voicing is being called for, not just a C bass note. But this type of symbol is hard to read, and in any case bitonality is seldom used in pop music chord charts, so you may never encounter such a chord symbol outside of a theory book.

Quiz

1. What term is used to describe a chord consisting of stacked 2nds?

2. What term is used to describe writing in which two instruments play different chords, or passages in different keys?

3. When the 3rd of a chord is replaced by a 4th, what is the chord called?

4. When a chord is described in a chord chart as an 11th, what other notes does it contain?

5. Why is there no such thing as a 15th chord?

6. What notes are contained in a Dmaj9? A B67#1 I? An Em l I? An F769#9?

7. What altered note is the same as the #11? What note would be the same as an aug 13 (if there were such a thing as an aug 13)?

8. What other chord contains the same notes as an E66? Describe the sound of a 6 chord.

SCALES

usic that consisted entirely of chord voicings would be interesting, but it wouldn't be very interesting for very long. Fortunately, there's more to music than chords. The framework provided by chordal harmonies can be expanded by adding extra notes - notes that are not part of the chord currently being played. These extra notes allow us to create music that's much more complex and expressive.

usic that consisted entirely of chord voicings would be interesting, but it wouldn't be very interesting for very long. Fortunately, there's more to music than chords. The framework provided by chordal harmonies can be expanded by adding extra notes - notes that are not part of the chord currently being played. These extra notes allow us to create music that's much more complex and expressive.

NON-CHORD TONES

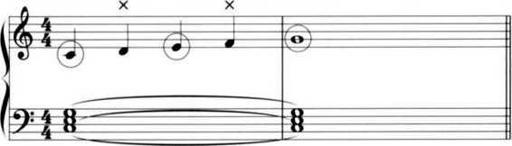

Take a look at Figure 7-1. While the left hand plays a C major triad, the right hand steps from one note to another. Three of the notes in this upper voice (the C, E, and G, which are circled in the figure) belong to the underlying C major chord. But the other two notes (D and F) are not found in the C major chord. These two notes are called passing tones, because the line played by the right hand uses them to pass from one chord tone to another.

Figure 7-2 is similar, but here the chord tones in the right-hand line are all E's, so we can't really say that the non-chord tones (F and D) are passing tones. When a voice leaves a chord tone in this manner, plays a nearby note, and then returns to the chord tone, the non-chord tone is said to be a neighboring tone. (The term auxiliary tone is also used.)

Figure 7-1. The line in the treble clef includes both chord tones (circled) and non-chord tones (marked with X's). When a line uses non-chord tones to move from one chord tone to another, the non-chord tones are called passing tones.