A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (77 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Although Scheffer issued a relatively tentative and-according to the genocide convention-accurate finding of"indicators of genocide," editorialists, nongovernmental advocates, and others criticized the Clinton team for using the term. They saw that hundreds of thousands of Albanians were being expelled but :not murdered. Since most equated genocide with fullscale extermination, they accused the United States of exaggerating the Serb terror in order to justify both the NATO bombing mission and the civilian casualties caused by it. Certainly, some of the frustration with the administration was warranted. It was not a coincidence that having avoided the g-word regarding Bosnia and Rwanda when it wanted to avoid acting, the Clinton administration applied the label proactively only in the one intervention for which it was trying to mobilize support. In this case, a finding of "genocide" would not shame the United States; it would enhance its moral authority. Still, a straight reading of the genocide convention did capture the kind of ethnically based displacements and murders under way. Milosevic was destroying the Kosovo Albanian populace.

U.S. officials were also faulted for their supposedly exaggerated estimates of the number of Albanians killed. In fact, records reveal that most were cautious about suggesting figures. At a State Department press conference on April 9,1999, reporters pressed Scheffer for a numerical estimate of Albanian deaths. "I think it would be very problematic to speculate at this time on a number," Scheffer said." I fear [any estimate] would be too low if I did speculate. I think we have to wait to find what the death count is."" On April 19, State Department spokesman James Rubin declared, "There are still 100,000 men that we are unable to account for, simply based on the number of men that ought to have accompanied women and children into Macedonia and Albania." Rubin reminded reporters of Serb behavior in the recent past. "Based on past practice," he said, "it is chilling to think where those 100,000 men are. We don't know.";" Rubin was right. Nobody could then know.

Rubin's formulation became the model for other U.S. officials. Most noted that military-aged men were being systematically separated from refugee columns. They reported concrete cases of mass executions and individual murders, estimated at 4,600. But although they may have assumed the worst, they did not leap publicly to conclusions. They distinguished the number of those Albanians they believed were already murdered and those who were simply unaccounted for. On May 7, 1999, for example, Defense Department spokesman Kenneth Bacon also said:

100,000 military-age men are missing. We reckon that over 4,600 have been killed in mass executions in over 70 locations.... This could well be a conservative estimate of the number who have been killed in mass executions. Some may have been used to dig graves. Some may have ... been ... forced to support the Serb military in various ways. We have reports that some have been used as human shields. Some may have died in the hills or working. We just don't know, and that's one of the mysteries that won't be resolved until this conflict is over.

As reporters continued to grill him, Bacon seemed to lose patience. Sounding like Claiborne Pell during the 1988 Kurdish crisis, he reminded his audience of the obvious: "The fact that they're missing means that we can't interview them and find out exactly what's happened to them"'°A few days later Secretary Albright told Americans that there would necessarily be many open questions until independent investigators gained full access. "Only when fighting has ended and the people of Kosovo can safe ly return home will we know the full extent of the evil that has been unleashed in Kosovo;' she said. "But the fact that we do not know everything does not mean we know nothing. And the fact that we are unable to prevent this tragedy does not mean we should ignore it now.""' Albright was breaking from past U.S. practice by relaying what she thought to be the morbid truth even though she knew it would likely increase the pressure for the United States to intervene with ground troops.

In the year following Milosevic's surrender, investigators began digging up mass graves in Kosovo. In September 1999 a Spanish forensic team claimed that it had uncovered war cringes' victims, but far fewer than it had expected. The chief inspector in a Spanish unit, Juan Lopez Palafox, declared, "We were told we were going to the worst part of Kosovo, that we should be prepared to perform more than two thousand autopsies and that we should have to work till the end of November. The result is very different. We uncovered 187 corpses and we are already hack." Spanish investigators broug:at new expectations to their reporting in Kosovo. "In former Yugoslavia," Lopez Palafox continued, "there were crimes, some of which were undoubtedly horrific, but nevertheless related to the war. In Rwanda we saw the bodies of 450 women and children, heaped up inside a church, and all of their skulls had been split open.""The Rwanda genocide had set a whole new, modern standard for genocide. Body counts were compared, and the Kosovo tally was said not to measure up.

In November the UN war crimes prosecutors announced that some 4,000 buried bodies had been found. Journalists took this "low" figure as proof the U.S. government had lied. "The numbers are significant, but nowhere near what U.S. officials had indicated during the fighting," CNN's Wolf Blitzer said. "That's 7,000 short of the 11,000 that had been reported to the U.N. after the war." Blitzer's report made no mention of the more than 300 sites that had not been probed at all or of the Serbs' notorious tampering with evidence. Instead, he quoted a former Bush administration official who described the governmental "temptation to take poetic license with the data.

The truth of what Serb forces did to Albanians between March 24, 1999, and June 10, 1999, is of course still emerging. As of November 2000, the UN war crimes tribunal at The Hague confirmed the 4,000 bodies or parts exhumed from more than 500 sites.'' Officials stressed that not all of those executed or beaten to death in Kosovo had been buried in mass graves at all. Many were dumped into roadside ditches, wells, and vegetable gardens. Some Albanian victims who were initially piled into pits for burial were removed. Bulldozers arrived to cover the Serbs' tracks by scattering body parts in multiple sites or by incinerating the bodies in bonfires or factories. In the village of Izbica, for instance, Albanian villagers buried some 143 bodies after a Serb massacre before they fled in early April. Spy satellite images confirmed the existence of 143 graves. But by the time tribunal investigators arrived in June 1999, the only sign of vanquished life that remained were earthmovers' caterpillar tracks, which crisscrossed the area. The bodies had vanished.

Careful scrutiny of American and refugee claims reveals that U.S. government predictions and refugee descriptions proved remarkably accurate. Despite the frantic dash most refugees made to the border and the terror of the experience, Human Rights Watch has confirmed some 90 percent of what its investigators were told. The UN prosecutor at The Hague also found that four out of five Kosovar refugee reports of the number of bodies in the graves were precise.

The bodies keep turning up. In 2001 some 427 dead Albanians from Kosovo were exhumed in five mass graves that had been hidden in Serbia proper. An additional three mass grave sites, containing more than 1,000 bodies, were found in a Belgrade suburb and awaited exhumation. Each of the newly discovered sites lies nearYugoslav army or police barracks.54

Some of the wildest rumors that circulated during Serbia's deportation operation have been confirmed. While NATO was still bombing, essayist Christopher Hitchens received a letter from a former student in Serbia that a friend of his, a truck driver, had been ordered by the Yugoslav army to pick up Albanian corpses in his refrigerated vehicle and drive them into Serbia. Hitchens, a staunch backer of NATO's intervention, did not publicize the letter because even he deemed it "weird and fanciful." He was leery of wartime "rumors."" But in July 2001 Zivadin Djordjevic came forward to confirm the rumors. Djordjevic was a fifty-six-year-old diver in Serbia who made his living plunging into the Danube River to rescue vehicles and drowning victims. In April 1999 he was asked to examine a white Mercedes freezer truck found bobbing in the Danube near the town of Kladovo, 150 miles east of Belgrade. Believing it was just another unlucky vehicle, Djordjevic donned his wet suit and swam up to the back door of the truck. When he opened it, he discovered a ghastly cargo of men, women, and children. He first saw what lie said was "a half-naked, beautiful, black-haired woman with great white teeth"Then he discerned two boys "no older than 8 years old.-The tangled corpses slid into his arms. As he wrestled one back into the truck, another would slither out. "It was the first and only time in my life I have been confronted with such horror," the diver later said."'

Two days after NATO began bombing in 1999, we now know, Milosevic ordered his interior minister,Vlajko Stojilkovic, to "clear up" the evidence of war crimes in Kosovo. Stojilkovic used all available refrigeration trucks to remove corpses from execution sites in Kosovo and to destroy or rebury them in Serbia. According to witnesses, some of the corpses were incinerated at furnaces in Bor, Serbia, and Trepca, Kosovo. Milosevic's government thus not only permitted, encouraged, and ordered its security forces to murder the Albanians, but it also tried to cover tip the crimes. The UN tribunal has received reports that some 11,334 Albanians are buried in 529 sites in Kosovo alone.''

As high as the death toll turned out, it was far lower than if NATO had not acted at all. After years of avoiding confrontation, the United States and its allies likely saved hundreds of thousands of lives. In addition, although prospective and retrospective critics of U.S. intervention have long cited the negative side effects likely to result, the NATO campaign ushered in some very positive unintended consequences. Indicted by the UN war crimes tribunal for Serbia's atrocities in Operation Horseshoe and defeated in battle, President Milosevic became even more vulnerable at home.The Serbian people realized that a Milosevic regime meant corruption, oppression, death, and a future of international isolation and economic desola- tion.When a Serbian economics professor, Vojislav Kostunica, ran against Milosevic on a platform of change in Serbia's September 2000 election, Milosevic was roundly defeated. When Milosevic attempted to contest the results, the country's miners, workers, police, and soldiers joined with Belgrade's intellectuals and students to end his deadly thirteen-year reign. In March 2001 the Kostunica government arrested Milosevic and in June 2001, in return for some $40 million in urgently needed U.S. aid, Belgrade delivered him to The Hague. The political turnover finally enabled Serbia's citizenry to begin reckoning with Serbian war crimes, a prerequisite to any long-term stability in the region.

The man who probably contributed more than any other single individual to Milosevic's battlefield defeat was General Wesley Clark. The NATO bombing campaign succeeded in removing brutal Serb police units from Kosovo, in ensuring the return of 1.3 million Kosovo Albanians, and in securing for Albanians the right of self-governance. Yet in Washington Clark was a pariah. In July 1999 he was curtly informed that he would be replaced as supreme allied commander for Europe. This forced his retirement and ended thirty-four years of distinguished military service. Favoring humanitarian intervention had never been a great career move.

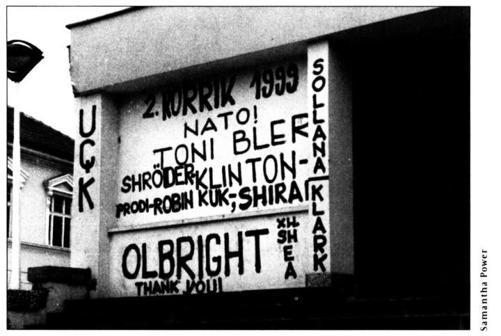

Graffiti tributes to Western leaders scrawled in Pristina by Kosovo Albanians after Serbia's surrender.

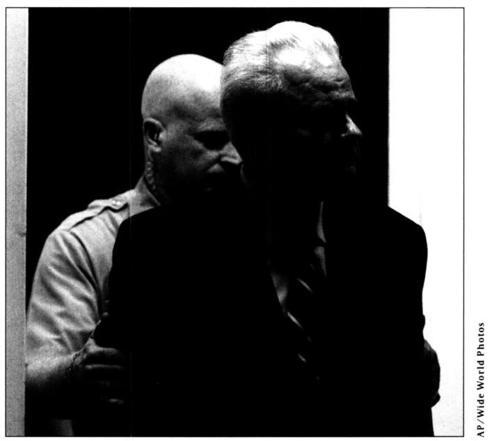

Former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic escorted by a UN security guard into the courtroom at The Hague, duly 2000.

Chapter 13

Lemkin's

Courtroom Legacy

Courtroom Dramas

When Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic arrived at the International War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague, he was the thirty-ninth Yugoslav war crimes suspect to end up behind UN bars. He was initially indicted only for crimes against humanity carried out in Kosovo, but the UN prosecution later broadened the indictment to charge him with genocide in Bosnia. His wife and political accomplice, Mirjana Markovic, condemned the tribunal as a "concentration camp with gas chambers for Serbs" In his initial courtroom appearance, Milosevic lashed out at the "false tribunal" and refused to accept legal counsel. When asked if he wanted to hear his fifty-one-page indictment read to him, he snorted, "That's your problem."' At a subsequent session he elaborated: "Don't bother me and make me listen for hours on end to the reading of a text written at the intellectual level of a 7-year-old child, or rather, let me correct myself, a retarded 7-year-old."'