A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (81 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

The Hague court has grown beyond anybody's expectation. The very same institution that had a budget of $11 million in 1994, spent more than $96 million in 2000. The detention center initially housed only the relatively low-ranking Tadic; by November 2001 it held forty-eight inmates. And the one-person staff that originally consisted of only deputy prosecutor Graham Blewitt topped 1,000 in 2001, including some 300 on the prosecutor's staff. A court that once occupied a few rooms of the Dorint Insurance building was bursting at the seams of the sprawling complex and on the verge of annexing additional neighborhood property. With three functional courtrooms, a visitor to the Krstic trial could also hear the concentration camp guards from Omarska testifying in their own defense or listen to the wrenching reminiscences of an elderly Muslim woman testifying about the massacre of her family. After a slow start, the Clinton administration played a key role in helping the institution grow. During Clinton's second term, the United States provided the tribunal with more financial support than any other country, as well as senior personnel. Most significant, the United States turned over technical and photographic intelligence that greatly facilitated trials like that of General Krstic. Of course, Clinton also left office while the Bosnian war's three leading men, Mladic, Karadzic, and Milosevic, remained at large.

When it came to rounding up top suspects, the UN court for Rwanda was more successful than its better-publicized and better-resourced counterpart at The Hague. In Bosnia, because the gains of ethnic cleansing were preserved in the Dayton deal, suspected war criminals were able to take shelter, and even prosper, in territory that after the war continued to be controlled by their ethnic group. In Rwanda, by contrast, the ethnic Tutsi who began governing the country after the genocide threatened to arrest and execute killers who dared return. Most of the genocide suspects thus fled to neighboring African countries, where they were apprehended and extradited to the UN court in Arusha.The fifty-three held in custody at the Arusha detention center included many of the highest-ranking officials of the Hutu-controlled government and key planners and inciters of the genocide, including not only ringleader Colonel Bagosora, but the prime minister, the director of Radio Mille Collines, and the leaders of the various machete-wielding militias.

Despite its impressive record of locking up the once-fearsome geno- cidaire, however, the court has struggled. Early on, lawyers and judges were hampered by intermittent phone service, the absence of internet access, and scant research support, so that the prosecution staff often could not communicate with investigators in the field. But even after the logistic headaches eased, the court was plagued by corruption, nepotism, and mismanagement. Squirreled away in east-central Africa in a jumping-off spot for safaris and trips to nearby Mount Kilimanjaro, many staff members lazed about Arusha on cushy UN salaries. The court was so dysfunctional that a few of the early court reporters were found unable to type.

Although some of the corrupt early employees were fired, the tribunal still had not gained its stride by late 2001. International observers continued to fault the snail's pace of the proceedings. Repeated delays exasperated Rwanda's survivors. In addition, human rights advocates began noting the severe due process ramifications to locking up defendants for years on end without trial.

Courting Attention

Despite the presence of high-powered defendants in UN custody, none of the early trials had the effect on survivors that the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official in charge of Jewish deportations, for instance, had on Israelis. Citizens in Rwanda and Bosnia paid almost no attention to the court proceedings. Israelis recall the days when they huddled around their radios to hear for the first time the details of Nazi horrors, whereas Bosnians and Rwandans just shrug when the courts are mentioned. They are deemed irrelevant to their daily lives. Ignorance is rife.

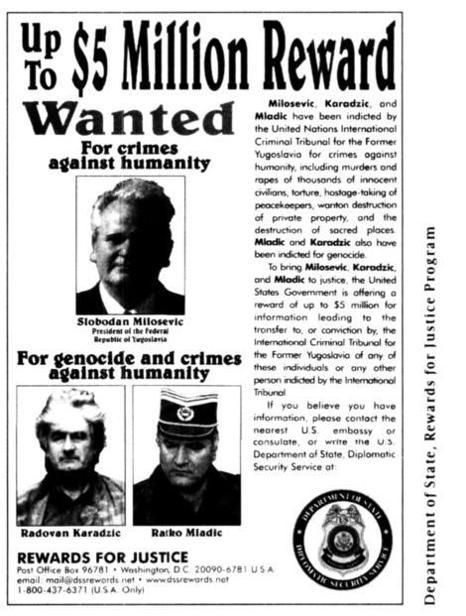

In 1999 the State Department issued a $5 million ransom for information leading to the apprehension of Yugoslavia's three leading war crimes suspects. U.S. forces in the Balkans were not ordered to arrest the indictees.

For their first six years of existence, the tribunals themselves did virtually nothing to reach out to the countries on whose behalf they were doing justice. The courts thus missed opportunities to deter, to legitimate victim claims, and to establish individual (as opposed to collective) guilt. Although almost every Bosnian had a television set, the trials at The Hague were not broadcast live back to the region. Indeed, shockingly, the UN Press Office did not translate its press releases into Serbo-Croatian until February 2000. Only a few of the indictments were available online. Judges and lawyers accustomed to working within national judicial systems that needed no promotion had spent their careers assiduously shying away from the press; they had no experience attracting attention, as they needed to do if they were to engage Bosnians or Rwandans with the proceedings.As one senior lawyer in the court registry at The Hague put it:

In Western countries courts automatically have a certain respect. They are recognized in the community. People understand their role; they are covered in the press; citizens may serve in juries. They simply don't need to promote themselves. But if you are doing what we are doing, hundreds of miles away, in a different language under a different system, you have to do things that courts don't ordinarily do.... If you just sit here and hear cases, you simply won't get the job done.

The trials also moved so slowly that local interest was hard to sustain. Conducting complex investigations in foreign lands through interpreters years after the crimes and without much pertinent international legal precedent was no easy chore. Courtroom participants had to adjust to the hybrid nature of the law itself. The tribunals' statute took its adversarial nature and rules of evidence from the Anglo-American tradition, but, as in continental Europe, it denied trial by jury, allowed hearsay, and permitted the questioning of defendants. As precedents were set and the tribunals began to establish a jurisprudential, historical record of the war, the trial pace began to quicken somewhat.

But the slowness could not be blamed on the novelty and complexity of the process alone. Tribunal courtooms in the The Hague and Arusha were more often vacant than full. Judges allowed innumerable breaks in the pro ceedings and rarely challenged the relevancy of the counsels' frequently rambling lines of inquiry. Defense counsel earned in excess of $110 per hour, an unremarkable rate in the United States and Western Europe but a monthly wage, or windfall, for Balkan or African lawyers. The incentive structure thus invited prolix posturing, as defense lawyers stalled trials in order to be able to bill more hours.

In late 1999 the Hague tribunal finally launched an outreach program designed to help the trials reach citizens of the fornier Yugoslavia. This small office of five was set up to conduct educational seminars, arrange visits for courtroom personnel to the Balkans, and attempt to generate local media coverage. Although it was a tall order to win (or open) the minds of a skeptical Bosnian audience, the new outreach office made a few early inroads. With its help, Mirko Klarin, the same independent journalist who in 1991 had recommended the establishment of an international war crimes tribunal and who had covered the Hague court's proceedings since they began, prepared fifteen-minute weekly television summaries of the tribunal's activities. Only Bosnia's independent television networks picked them up, but this at least meant some viewership. One more daring proposal was to stage actual portions of the UN trials on Balkan soil. Some groaned at the mammoth security risks of hauling defendants, lawyers, and judges to a volatile region. Others argued that the money could be better spent on investigations or that the gimmicky nature of a road trip would necessarily make the proceedings seem more like show trials than trials. The greatest boon to interest in the tribunals will be the Milosevic trial, which will start in 2002.

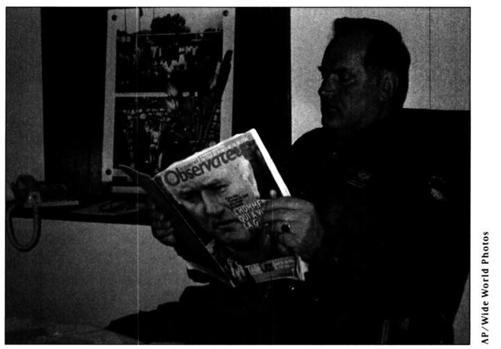

Indicted by the UN war crimes tribunal for war crimes and genocide in 1995, Bosnian Serb army commander General Ratko Mladic remained at large as of December 2001. Mladic here relaxes in March 1996 at one of his command posts.

Radio is Rwanda's media outlet of choice. But although the UN tribunal prosecuted well-known, high-level suspects right from the start, few Rwandans listened to the proceedings. In 2000, Internews, an entrepreneurial American NGO, prepared a documentary in the Rwandan language on the UN trials in Arusha. New York producer Mandy Jacobson arranged town-hall-style screening sessions throughout Rwanda. The Rwandans who gathered had never before seen trial footage and gasped at the sight of their tormentors in the dock.

Truth-Telling

For all of the imperfections of the two courts, one reason many tribunal staff were converted to the idea of moving portions of trials to the Balkans and Rwanda was that they thought the proceedings were increasingly delivering messages essential to reconciliation. For the first time, the perpetrators of genocide and crimes against humanity were being forced to appear before a court of law, where their self-serving arguments could be formally challenged. If Serbia's Slobodan Milosevic and Rwanda's Theoneste Bagosora once insisted that "uncontrolled elements" were carrying out the killings, the prosecutors at the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals had the opportunity to dismantle these claims, showing that these men were very much in control.The evidence proved that what were once called "failed states" were in fact all too successful in implementing their designs.

In order to achieve their truth-telling aims, prosecutors presented damning visual and oral evidence, including documentary paper trails and hundreds of witness interviews. The very same defendants who claimed to be "out of the loop" were proven repeatedly to be central to it. The lawyers spelled out the elaborate command and control arrangements within each of the factions, demonstrating that military and political leaders were in close contact with the forces committing atrocities.

In the Srebrenica trial, for example, General Krstic said that General Mladic, the true villain, had already dispatched him to Zepa when Mladic began killing the men around Srebrenica." Krstic said this alternative assignment was "no accident" because General Mladic would never have had the nerve to order the murder of so many men in his presence.Yet the prosecution presented evidence that placed Krstic at the scene of the crime and that recorded his directives. They showed Bosnian Serb leader Karadzic later hailing Krstic as a "great commander" and decorating him for his heroics in "planning and implementing the Srebrenica operation.""

In both the Yugoslav and the Rwanda tribunals, the self-serving defendants have aided the prosecutors. In the hopes of securing lighter sentences, the suspects have frequently turned on one another. This has facilitated the prosecution of several perpetrators and enabled the courts to establish certain "facts" by broad consensus. Krstic, as mentioned, implicated General Mladic and five more junior officers, describing them as "mad" and responsible for "anything that might have gone on""

The trials have also belied a second claim made by the perpetrators (and, incidentally, by Western policymakers)-that the "ethnic" violence simply exploded spontaneously. Mounds of detailed evidence have demonstrated sophisticated planning and organization behind the bloodiest operations. Elaborate requisitioning of men, vehicles, ammunition, and remote locations were indispensable to most large-scale massacres. The Rwanda trials have shown how lists of Tutsi victims were prepared and systematically distributed down the chain of command, from the state level, to the regional level, to the prefectures, to the communes, and then to the individual hamlets, or cellules. That perpetrators and planners were so few in number and so identifiable indicated that they also could have been stopped.

In the case of the Yugoslav tribunal, although perpetrators clearly committed their crimes cn ethnic grounds, the climate in the detention center that houses war crimes suspects has revealed the limits to much of the ethnic passion in the Balkans. The ruddy-faced, chain-smoking Irishman named Tim McFadden who runs the UN prison configured the facility to mandate mixing among prisoners of all ethnicities. None of the prison floors are segregated by nationality. Those dedicated to killing members of rival ethnic groups have thus been forced to watch television, take English or pottery classes, or lift weights with their onetime foes. The inmates have not become security risks to the guards or to one another. Ironically, as the trials have progressed and indictees of the same ethnic group have begun implicating one another in an effort to mitigate their own sentences, severe intra-ethnic security risks have arisen. McFadden is now concocting schemes to separate members of the same ethnic group who once conspired.