A Thousand Sisters (15 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

I'm so sorry. I don't know Susan Voss from Illinois or Patty Philips from Little Rock or Teisha Johnson from Atlanta. (Amazingly, in two cases I do happen to know their sisters.)

I've found myself animatedly explaining the details of American life that the women's sponsors have written about. I give spontaneous yoga demonstrations; tell them what it means to put a dormer on the house; describe

Disneyland (a place with giant, magic talking mice and roller coasters, where people pay to get scaredâfor fun!).

Disneyland (a place with giant, magic talking mice and roller coasters, where people pay to get scaredâfor fun!).

For the Congolese women, getting a letter from an American sponsor is kind of like an American woman getting a personal note from Julia Roberts. Even if she told you about her fabulous time at the Oscars, would hearing about her life make you jealous or depressed? No! You'd frame it and put it on display. Or at least tack it up on the fridge, so you could tell your friends, “Oh, yeah, Julia and I are tight. I'm totally on her Christmas card list.”

I am not the only sponsor who hasn't written. It turns out that not writing is more the rule than the exception. For every one letter sent by a sponsor, three are sent by program participantsâexactly the opposite of what I would have guessed.

A few days ago, a lone woman approached me and showed me her sponsorship booklet. “I've been in the program eleven months with no letter,” she said.

I fessed up to her. “At the beginning, I didn't write to my sister either,” I said. “But she was still very important to me.” Then I ripped off a sheet of colorful stationary (I've learned to always keep it on me for these occasions), and fired off an inspirational note to the woman standing in front of me, announcing, “You are officially my adopted sister.” I stuffed it with a couple of postcards and photos of my family.

Therese, my first sister, had noticed I didn't write. When she was just about to graduate the program, I received a batch of three letters she had posted nine months before. (The surge of new sponsors after the

Oprah

report created a massive backlog of letters.) She wrote, “I used to write to you, but you never reply. I wonder why.”

Oprah

report created a massive backlog of letters.) She wrote, “I used to write to you, but you never reply. I wonder why.”

Oy vey!

I scrambled to write her a long note in a greeting card, continued it on legal paper made folksy with flower stickers, and stuffed it in an envelope with postcards and family photos, scrambling to compensate for the months she waited for my reply that didn't come. I posted my letter to her on her last day in the program. I have no idea if she ever received it.

I scrambled to write her a long note in a greeting card, continued it on legal paper made folksy with flower stickers, and stuffed it in an envelope with postcards and family photos, scrambling to compensate for the months she waited for my reply that didn't come. I posted my letter to her on her last day in the program. I have no idea if she ever received it.

I vowed to be better about corresponding, and in the past year I've written each of my sisters four letters.

Today, I'm meeting Therese in person. I'm embarrassed, but I'm hoping the fact that I've traveled all this way will exonerate me for not writing. My meetings with women's groups have been nonstop, and no meeting has been like that first hard-charged campaign for cash, after which I slinked upstairs to the office, depressed. Jules, head of the sponsorship staff, approached to ask, “How did your meeting go today?”

I told him.

“Lisa, we could have told you this would happen,” he said. “It is why we don't pass on email or postal addresses. They are poor and they are city women. Of course they will ask you for more money. It's a matter of survival. In rural areas it will be different.”

In fact, it hasn't happened again. All of my subsequent meetings have been ebullient celebrations. I tell the women I meet about

Oprah,

my run, the movement, all the women who support them from America. Then we go around in a circle and each tells me about “the trouble I got from war.”

Oprah,

my run, the movement, all the women who support them from America. Then we go around in a circle and each tells me about “the trouble I got from war.”

The war stories are endless. But so are the success stories. And the thanks.

I've learned a couple of Swahili words, just from hearing them so much:

Aksanti,

thank you, and

Aksanti sana,

thank you so much. And again,

Furaha,

meaning joy or “I am happy.”

Furaha sana.

So much joy. I am so very happy. “We no longer rent. We got our own land. I pay them to work on my farm.”

Aksanti,

thank you, and

Aksanti sana,

thank you so much. And again,

Furaha,

meaning joy or “I am happy.”

Furaha sana.

So much joy. I am so very happy. “We no longer rent. We got our own land. I pay them to work on my farm.”

“I lost all things, burnt. I lost dignity. You dignified me.”

“I regained joy.”

“The help you are sending helps us to be human beings, really.”

“Today I can really breastfeed my baby because I am eating well.”

“If only you could open my heart to see how happy I am to see you. I am buying hens. Whenever I am hungry now, I slaughter one.”

“If I was a bird, I would fly and meet you in America.”

“If my kid grows up, it is because of support from you.”

“I don't know what measurement I can use to measure my joy.”

“I feel somehow a person in life, a woman in life. I didn't think I would feel like other women.”

“You have to continue up to the coming of Jesus.”

“Thanks, thanks, thanks.”

“May God bless and bless and bless and bless.”

“It doesn't arrive every day to be in this kind of joy. But I am really happy.”

Â

WE'VE DRIVEN FORTY-FIVE MINUTES up the long, winding road that hugs the hillsides above Lake Kivu. With Congolese military hanging around the ramshackle shops at the village crossroads, I emerge from the SUV. Squishy clay mud sucks my flip-flops under.

The women who have been waiting burst into song. The men and children stand back. It's a women's party today and they are not invited. Singing and dancing continues during their long procession to the Women for Women compound. The reception today seems almost surreal, the women in saturated colors against the lush landscape dampened with morning rain. Two women lead the group in an impromptu call-and-response chant of endless thanks.

“My kids couldn't go to school, and now they have education because of you.”

“We were hungry. Now we eat because of you.”

Twenty minutes into the reception, Hortense leans over to me and says, “The woman in yellow is your sister Therese.”

She is a modest woman, perhaps early forties. She wears a traditional African dress, crisp and precisely wrapped, in vivid yellows and purple. I tower above her. (My friends will later laugh at me in the photos. “You look like an Amazon next to her!”)

“Did you ever receive my letter?” I ask, hugging her.

“I got one letter.” She says, “I had already finished the program.”

“Did you get photos?”

“I love them,” she says. “I told my husband you were coming. He wanted to meet you too, but this place is only for women.”

“You said in your letter that your husband had been taken to the bush. Is it the same husband or did you remarry?” I ask.

“I have many, many things to tell you.”

We file into the cement classroom with eight other sisters, whom I greet individually. I kneel down next to a sister in a leopard-print headscarf and a dress with puffy sleeves and shiny embroidery. I look at her booklet.

Beatrice. Her sponsor line reads: Kelly Thomas.

Though it would have been easy to schedule this meeting on a day that fit Kelly's needsâjust a minor coordination via emailâher plans prevented her from making it today to meet her own sister. She entrusted me with a letter and photos to pass along to Beatrice. “It's probably better if you don't tell her I traveled all this way, but didn't make it to see her,” she told me.

Why on earth would I want Beatrice to know that?

Gesturing to Beatrice, I tell Hortense, “Don't mention that Kelly is in Congo.”

“Beatrice was called here to meet Kelly,” Hortense says, “I've already told her Kelly didn't come.”

Ouch

. Beatrice keeps her eyes cast downward to hide the awkward, sinking look of someone trying to hide disappointment. I pull out Kelly's packet, tied with a bow, and say, “Kelly was so sorry she couldn't be here today. She wanted to meet you so badly. She asked me to send you her love. It just wasn't possible.”

. Beatrice keeps her eyes cast downward to hide the awkward, sinking look of someone trying to hide disappointment. I pull out Kelly's packet, tied with a bow, and say, “Kelly was so sorry she couldn't be here today. She wanted to meet you so badly. She asked me to send you her love. It just wasn't possible.”

I snap a shot of Beatrice holding the photo of Kelly and her husband.

We move on with the meeting, while Kelly's sister holds a half-smile, fingering the photos and letter quietly. Still, she looks like a person who's shown up at the wrong party, like she wouldn't mind disappearing.

We begin with “the trouble I got from war,” but conversation quickly shifts when one of my sisters says, “Some children died.”

That's one of my talking points. I ask, “How many have children who have died?”

Six out of nine raise their hands.

“How many of you have had more than one child die?”

They hold up their fingers. A couple of them hold up two fingers. One of them holds up three fingers. Another woman raises four. “Four children died.”

Another explains, “The twins died, and a baby after.”

They each launch into their own one-line explanations, “The baby was tired after birth and didn't breast-feed.”

“My 13-year-old daughter died from anemia, after she had four packs of blood.”

“Two babies, both died at the clinic. I remain childless.”

Therese adds, “One child died because of bad living conditions in the bushes. We buried her in the yard.”

These stories always shock me, though they shouldn't. I've been citing the statistics for years. Congo's child death rate is twice that of sub-Saharan Africa, which is already the highest in the world. Fifteen hundred people continue to die every day as a result of the war. In fact, less than one-half of one percent of the war-related deaths in Congo are violent. The vast majority of the deaths are due to the war's aftershocks, primarily easily curable illnesses. Almost half of the deaths are children under the age of five.

We get so wrapped up in the discussion about everyone's lost children that the meeting time flies by. I hear almost nothing from Therese, who remains quiet and unassuming. When it's finally her turn to speak, she says, “I escaped with my children. It was dark, but I saw them take my husband away.”

The Interahamwe took five girls and eight other men that night. “The abducted girls escaped death, but the other eight men were tied on crosses and killed, except my husband.”

“Did your husband become an Interahamwe soldier?” I ask her.

“He was a slave, cooking,” she says.

“He was sent to get firewood the day he escaped,” she continues. “When he came back home, they sent letters. They say they will come for him one day.

My husband is a good cook, so they say they want him back because they can't find someone else who cooks like him.”

My husband is a good cook, so they say they want him back because they can't find someone else who cooks like him.”

“Can't you move to Bukavu and open a restaurant?” I ask. “Do you still live in the same house?”

“We're still there.”

Sadly, we are out of time. We take a few group photos and I give Therese a big hug. We wave to each other as I pull away, and I call back to her,

“Kwa heri!”

Goodbye.

“Kwa heri!”

Goodbye.

On the drive home, as we peel around corners that reveal soaring views of Lake Kivu, the meeting feels like a letdown, as much for Therese as for me. After her months of waiting and wondering who Lisa Shannon might be, and after my years of thinking about her fuzzy, dark photo while I ran miles on the trail, rehearsing what we might say to each other, I've met her in person. I've embraced her. But we spoke for less than five minutes. We exchanged only a handful of sentences. I know almost nothing more about her.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Gift from God

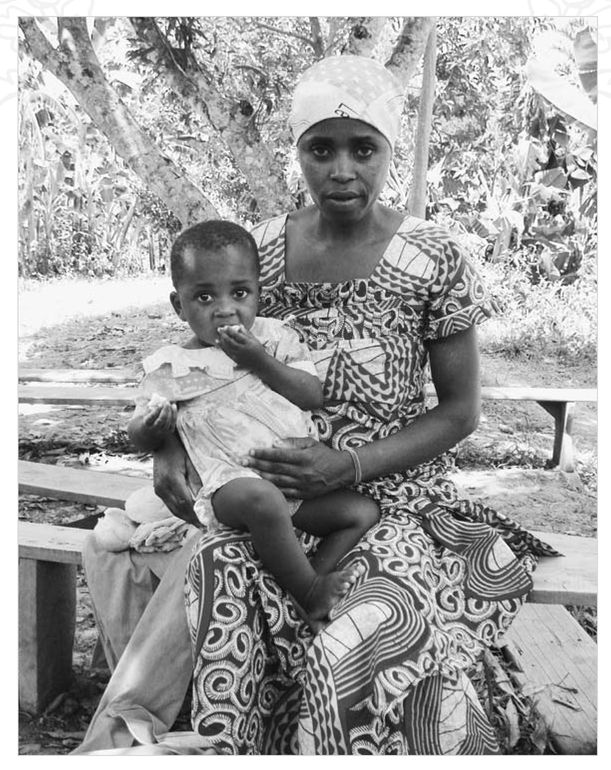

SO THESE ARE

the Walungu sisters, whose black-and-white photos radiated damage. Here in Walungu, an hour from Bukavu, the town itself is secure. It's crawling with Congolese Army and UN officials, but it attracts Women for Women participants from villages neighboring “the forest” (a.k.a. Interahamwe territory), like the notorious Kaniola, five miles down the road. That is plenty to account for the shell-shocked looks in their photos.

the Walungu sisters, whose black-and-white photos radiated damage. Here in Walungu, an hour from Bukavu, the town itself is secure. It's crawling with Congolese Army and UN officials, but it attracts Women for Women participants from villages neighboring “the forest” (a.k.a. Interahamwe territory), like the notorious Kaniola, five miles down the road. That is plenty to account for the shell-shocked looks in their photos.

Wandolyn sits close to me and weeps. She hasn't cracked a smile since we met a few minutes ago. I try to break the ice. “Did you get my letters?”

She ticks her tongue, looking away.

I show her the letters she wrote to me. “I saved them. When I was running, I had your face in my mind, sometimes for hours. I saw in your photo, in your eyes, that you've been through difficult things.”

She covers her mouth, mumbling something. Hortense says, “She remembers her difficulty. That is why she is weeping.”

“Would you like to talk about it?” I ask.

It's a smaller group today, only the four sisters, so we have the luxury of time.

“Congolese soldiers came to our village and raped me,” Wandolyn says. “At the hospital, they asked why I had kept silent. It was then I knew I was pregnant from the rape.”

I keep my hand on her shoulder.

Other books

Chained Cargo by Lesley Owen

The Hound of the Sanibel Sunset Detective by Ron Base

Loving Siblings: Aidan & Dionne by Catharina Shields

Vanquished by the Viking by Joanne Rock

SomeLikeitHot by Stephanie

Mrs. Jeffries Speaks Her Mind by Brightwell, Emily

Angelica's Smile by Andrea Camilleri

Fervent Charity by Paulette Callen

August: Mating Fever (Bears of Kodiak Book 2) by Selene Charles