A Thousand Sisters (18 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“The security is good,” she says. “No problem.”

“What about the Mai Mai?” I ask.

“I've had seven trips to Baraka with no problem,” she tells me. “The Mai Mai are very kind. We will see them on the way. The general is a good man, taking care of them properly. They do not bother people.”

The Mai Mai don't bother people? They must have a stellar spin machine, because that's not what I've heard in the conversations I've had with former child soldiers. Initially formed as a community-based defense force to fight foreign rebel groups, the Mai Mai are widely known for mass atrocities against the very people they claim to defend. As one Congolese told me in strict confidence, “The Mai Mai do everything any other militia does. But if you speak against them, they will come to your home at night and kill you and your family.”

At present, the Congolese government is attempting to engage the Mai Mai in what's known as “brassage,” a process of demobilizing combatants and integrating them into the Congolese Army. But tensions are brewing as some among the militia's leadership grow agitated at being left behind in Congo's emerging post-election political scene.

The Mai Mai do have one unifying thread: their use of witchcraft. The translation of “Mai Mai” is literally “Water Water”; the name comes from their belief that if they douse themselves with an herb-infused potion prior to battle, no bullet can penetrate them. By magic, whatever they encounter in battle will pass through them like water. Codes of Mai Mai behavior are based on traditional beliefs and range from wearing lucky sink plugs, to maintaining abstinence or committing rape prior to battle, as a source of power.

The pro-Mai Mai sentiment strikes me as more of a cultural courtesy. I've noticed Congolese rarely criticize other Congolese.

Maurice and I slip away to the market to stock up on Marlboros and a case of beerâemergency love offerings. We divide the cigarettes between us and tuck them away in our bag so they're ready in the event that we have to make quick friends.

Hortense sees the beer and shrugs. “I don't understand why you think of problems.”

We hit the road about four hours late and cut over the border into Rwanda to borrow a good stretch of road. Meanwhile, Moses blasts Shakira's “Hips Don't Lie.” I can think of very few songs that are less Congo-appropriate. Thank God they don't understand the English lyrics. When it's over, he rewinds and plays it again. And again.

A couple of hours later, we cross back to Congo and a different landscape: miles of flat, wide-open plains covered in grass and shrubs, with cloud-capped blue-green mountains in the distance. Tiny children spot us and leap to their feet, delighted. They run after us pointing, waving. To four-year-old Congolese kids, every white person must be with the UN. They

scream,

“MONUC-ay!”

which is the children's name for MONUCâthe French acronym of the UN mission in Congo.

scream,

“MONUC-ay!”

which is the children's name for MONUCâthe French acronym of the UN mission in Congo.

They also yell,

“Muzungu!”

“Muzungu!”

“What does

muzungu

mean?” I ask.

muzungu

mean?” I ask.

“White person,” Kelly says.

“Sometimes you can also call a Congolese a

muzungu

,” Hortense adds.

muzungu

,” Hortense adds.

“What is a Congolese

muzungu

like?” I say.

muzungu

like?” I say.

“They are an important person like your boss,” she says. “Someone who will take care of you, give you money.”

When we are outside the city of Uvira, we pass our first militia. The Mai Mai attempt to flag us down for a lift. Fortunately, this is a common issue with a common solution. All charitable vehicles display a special stickerâa gun with a red

X

through it, like a No Smoking sign, but with a gun instead of cigarette. It is a universal symbol indicating that the vehicle is for humanitarians only. No guns, and hence no militias, on board. It is surprisingly well respected. We breeze straight past the hitchhikers. Within a few miles, I lose count there are so many Mai Mai around. We make it into a road trip game, watching out for them like wildlife, trying to guess who is Mai Mai and who is Congolese Army.

X

through it, like a No Smoking sign, but with a gun instead of cigarette. It is a universal symbol indicating that the vehicle is for humanitarians only. No guns, and hence no militias, on board. It is surprisingly well respected. We breeze straight past the hitchhikers. Within a few miles, I lose count there are so many Mai Mai around. We make it into a road trip game, watching out for them like wildlife, trying to guess who is Mai Mai and who is Congolese Army.

“What about that one?” I ask.

Maurice and Hortense alternately answer, “Congolese Army.”

“What about those guys?”

“Mai Mai.”

I don't have a clue as to how they can tell the difference. To me, they look exactly the same. You could argue the Mai Mai look a little scruffier and occasionally wear red, but the Congolese Army is pretty ragtag too. Even after passing more than fifty Mai Mai, I still can't tell which is which.

We pull up to a gas station in Uvira, about halfway to Baraka. It's already past four in the afternoon. The fill-up takes forever. Hortense chats on the phone.

My cell phone is out of range, and I can't say I'm sorry. My mom has

been calling twice a day, giving me anxiety-ridden pep talks, as much to calm herself as to soothe me. I've tried to keep my reports lightweight and clean, partly for her peace of mind, but also because she takes notes and likes to broadcast “what Lisa said,” peppered with editorial embellishments, to the whole Run for Congo Women email list.

been calling twice a day, giving me anxiety-ridden pep talks, as much to calm herself as to soothe me. I've tried to keep my reports lightweight and clean, partly for her peace of mind, but also because she takes notes and likes to broadcast “what Lisa said,” peppered with editorial embellishments, to the whole Run for Congo Women email list.

Hortense approaches Kelly and me with some news. “The UN advises no travel after dark,” she says. “We will need to spend the night here and make the rest of the journey in the morning.”

We check into a grossly worn-down motel with open corridors and balconies. I bypass the Presidential Suite, with its crusty patchwork carpet, for a smaller, more basic room. I peek out of the sliding glass doors to the panoramic view of Lake Tanganyika, the longest lake in Africa, which is swarming with mosquitoes. I retreat and lock the sliding glass doors. Double check the locks. Triple check the locks.

I lug my camera bag onto the bed, tuck in my mosquito net, snuggle up to my prized equipment, and spend the night spooning my camera bag.

I dream that a man breaks into the room and looms over me in my bed.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

A Separate Peace

I OVERSLEEP.

By the time I scramble to pull it together, the others have been waiting for me outside for quite some time. Today is my thirty-second birthday.

By the time I scramble to pull it together, the others have been waiting for me outside for quite some time. Today is my thirty-second birthday.

Outside of Baraka, the landscape tells the story of the past decade. It's obvious the region was abandoned for years. Villages are mostly ruins, their mud-brick huts, roofless and crumbling, are overgrown with weeds. Hortense says, “In the next village, there were only four civilian families left.”

We slow down as we drive through a village. I notice a large cement slab, painted with a mural: huts burning, soldiers hacking people with machetes. It reads: MASSACRE DE MAKOBOLA/BANWE, 20/12/1998.

Hortense points toward the hills and says, “They buried them up there.”

We pull off the main road and drive up narrow grass tracks. In a clearing above the village, a stone monument marks the site. A local villager tells us the story, which Hortense translates: “People hid along the waterways to escape war. Then those people came and called out that peace was recovered. Soldiers gathered people, telling them there was peace already. Once the people got here, they killed all of them.”

I follow Hortense behind the memorial. “They buried them here,” she says, pointing to a wild patch of yellow cosmos. “Seven hundred and two people were killed. They buried them in four graves.”

Three more mass graves, overgrown with weeds taller than I am, are just beyond the sunny wildflowers. Hortense repeats the story, boiling it down to basics. “They told the people there was no more war, gathered them, and killed them all.”

As we continue down the main road, spanking new huts on freshly cleared plots, paid for by refugee resettlement projects, are beginning to creep into the landscape.

We pull into Baraka, which has the distinct feel of a Wild West frontier town. Its wide main drag is a dirt road lined only with NGO offices. Congolese soldiers with guns linger on every corner, bored, just hanging out.

We dump our stuff at the spotless UN guesthouse. It is decorated in UN blue and white, with spare, utilitarian furniture; it feels like the kind of austere vacation cottage you might find on a Greek island. When I ask a group of UN staffers about security in the region, a young European woman answers. “The FDD [a Burundian militia] and other foreign militias are gone,” she says. “There is a Mai Mai general on the peninsula who's been making threats, but just rapes and looting for the moment. No attacks yet.”

I sit quietly for a moment in the spare, whitewashed community room, balancing my gratitude for a clean place to stay and the generosity of my hosts with the implications of what she has just dropped into our conversation. I contemplate this young, wild-haired woman, with her slightly sweaty, disheveled look and the crusty demeanor of a seasoned European aid worker. As a staff member of the UNCHR, her task is to encourage refugees to return from Tanzania. She is currently working on a video project she can use to convince people it is safe to return home.

“You don't consider rape a security threat for returning refugees?”

“Rape here is so common,” she says. “It's cultural.”

Wow.

I say nothing but allow the weight of her comment to settle in the room.

I say nothing but allow the weight of her comment to settle in the room.

Â

NEXT, WE HEAD out for our meetings.

As we pull up to the Women for Women center in a village south of Baraka, we are greeted with an archway of flowers. I'm presented with a little bouquet of marigolds, gathered in a rusty can, and a goat. A goat! That's whatâforty dollars? I've gotten lots of chickens and eggs, but this is remarkably generous. This may be the best birthday celebration I've ever had. Just one little snag: I'm a strict vegetarian.

I joyfully receive the squealing, upside-down little gal, grabbing her bound feet. I set her down. “Thank you so much for this wonderful gift! I am so grateful for your generosity, so proud of you all, that I am presenting her back to your group as a celebration of our friendship. I have only one condition. You must never hurt the goat. The goat is blessed. The goat is sacred. Never, ever kill this goat.”

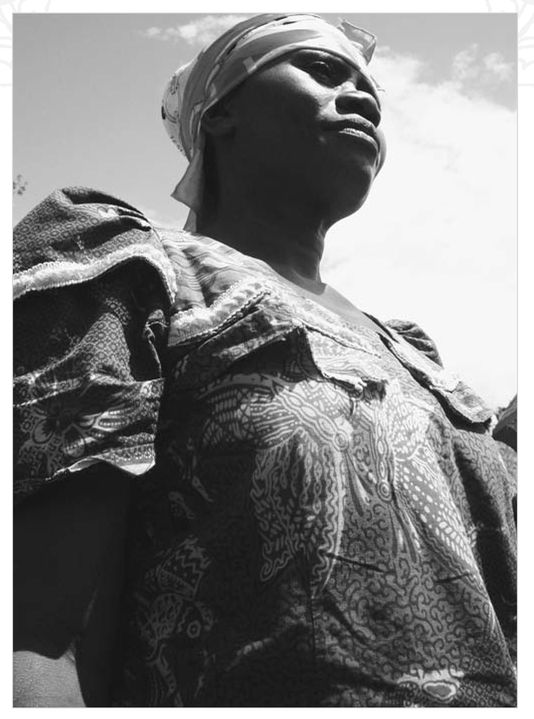

One of the participants leads the group in a cheer and dance. We settle into a large circle, shaded by ancient trees, and shoo away eavesdropping teenage boys. Almost all of these sisters have just returned from Tanzania, where they lived in refugee camps from eighteen months to ten years. Freshly resettled, the women boast about buying new plots of land every month with sponsorship funds. “We can buy a farm of twenty square meters for twenty dollars,” one says.

I've developed a quick survey to take at these meetings. How many have suffered a violent attack on their home? Had a relative killed? Lost a child? The women are always open. But I have never asked about rape directly at these forums. Maybe if I'm nonchalant, it'll put them at ease. I try to slip it in as part of my survey. “How many of you have been raped?”

A few hands go up then quickly retreat. It's a group of fifty, but only three women keep their hands raised. They stare at the others defiantly, stretching their hands higher. This is why oft-quoted statistics on rape in Congo are

ridiculously low. Even in a group that's all women, including Western women who have supported them financially, Congolese women won't talk about sexual violence in public, at least if no one else does.

ridiculously low. Even in a group that's all women, including Western women who have supported them financially, Congolese women won't talk about sexual violence in public, at least if no one else does.

Hortense shrugs. “They are hiding themselves.”

They stare at me blankly. Okay, that was tacky and insensitive. I shouldn't have asked such a personal question in a public survey. I try to rectify it, take them off the defensive. “In America, we believe if a woman is raped, it is never her fault. She has nothing to be ashamed of. So if any of you know someone who has been through this, I hope you will support her and let her know she didn't do anything wrong.”

I'm ready to call it a failed experiment. I'll just leave it alone.

We begin with “The trouble I got during war.”

Like most groups I have met with, these women are open about violent attacks. But an hour or so into our meeting, no one has mentioned rape. We land on the participant who led the singing earlier. She shifts on the edge of her wooden bench and speaks with a defiant tone. Even with the language barrier, I can tell by the others' body languageâthey are folding their arms, rolling their eyes, or adjusting their dressesâthey find her brash. Hortense translates. “When you asked about it earlier, we were not honest. Even if the others are hiding themselves, we were all raped. All of us.”

She continues with her story, motioning to her lap, slamming her fist between her legs, as she describes the attack. Some snicker with discomfort.

I thank her profusely for her courage to speak up and tell her story.

Later, others open up.

“They treated us the way they wanted. They met us in houses. They did what they needed.”

Other books

Sweetheart in High Heels by Gemma Halliday

Breed Her by Jenika Snow

Alpha Initiation (Alpha Blood #1) (Werewolf Romance) by Mac Flynn

Getting Familiar with Your Demon: That Old Black Magic, Book 4 by Redford, Jodi

Damaged by Alex Kava

To Hatred Turned by Ken Englade

Leap Day by Wendy Mass

Embracing Trouble (Trouble Series) by Bridle, Dee

Ask For It by Faulkner, Gail

Complete Short Stories by Robert Graves