A Thousand Sisters (20 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“But can she list their names and how old they were when they died?” I plead again. “Just a list?”

My pushing does not strike me as inappropriate in the moment, but she is swimming in her own thoughts, not listening to me. And Hortense does not translate; I take note of her cue.

“The others . . . I don't remember their names because I never want to talk about them.”

“Is it difficult?” I ask. “Would you prefer to not talk about them?”

With a crack in her voice and desperate, evading eyes, she ekes out, “I feel grief when I talk about them.”

We sit in silence for a long while.

Then I try again. “Do you remember other names, or do you want to just forget?”

Hortense snaps. “She has already given you five names. She has forgotten the names of the others because she never wants to talk about them.”

Fitina fiddles with her hands. An exasperated, pain-soaked smile spreads across her face. She strains to say, “They were all so young.”

Another long silence. The child still hangs on Fitina, resting her head on her grandmother's shoulder, watching me like I am the enemy. Even with the language barrier, the child sees what I've missed. My push to reduce Fitina's losses to a list has shut her down completely. There is nowhere to go.

Finally, I ask, “Is there anything you would like to say to other mothers in America?”

Fitina smiles shyly. “I send my greetings. If you are strong, it is my happiness.”

CHAPTER TWENTY

Water Water

WITHIN MINUTES OF

wrapping up with Fitina, we load onto the boat. The motor revs up and we are off.

wrapping up with Fitina, we load onto the boat. The motor revs up and we are off.

Cruising along the edge of the peninsula, Maurice, Kelly, and I sit outside on the wooden benches, exhausted from the day. I ask Maurice, “Were they Congolese military?”

“Ah, no. They were Mai Mai,” he says, as he leaves to retire inside.

Fear chemicals surge through me and I start to shake as I describe the soldiers to Kelly.

The boat slows down suddenly. The skipper and first mate are throwing on their life vests. This is not a good sign. They've been barefoot and shirtless most of the day.

I look ahead. A few miles in front of us, rain pours from storm clouds onto the lake; it looks like a steel wall.

“What's happening?” I ask Hortense.

“They are turning the boat around. We will spend the night in the village.”

With our new Mai Mai friends?

I ask rhetorically, “The Mai Mai . . . Do you really think it's safe?”

She flashes a big, tension-diffusing smile. “Safer than drowning trying to cross the lake, yes?”

The canvas canopy covering the deck flaps wildly, while the first mate grasps the canopy frame, trying to keep it from flying off. He maintains a tense gaze forward, anxiously blowing a plastic whistle as if to a drumbeat. I can only imagine that he's poising himself to send out a louder, high-pitched call for help should the boat capsize without warning.

So these are our choices tonight, more only-in-Congo choices. Would you rather be raped or watch your children starve? Drown, or camp with the militia?

So be it. We're sleeping over with the Mai Mai.

I grab my camera and try to capture it all on video. By the time the boat rocks to shore, slate-gray clouds blot out the remaining evening light, leaving just enough for my eyes to adjust and glean detail, but causing my video camera viewfinder to go black. I wobble back down the wooden plank.

I notice a little girl I walked with earlier today among the handful of women waiting for us. I touch her shaved head affectionately and say hello while the others disembark and Hortense talks to the women on the beach.

“They are glad we have returned,” she says. “They knew it would rain and were concerned.” (Much later, Maurice tells me what he overheard the villagers muttering to each other. Tension between the Congolese Army and the Mai Mai is at its peak, they were saying; it could erupt into gun battle at anytime.)

I kneel on the pebbled shore and grope around putting my camera away. The first fat raindrops hit, warning that a downpour is moments away.

“We must hurry!” Hortense calls back to me, chastising me for dallying.

I don't understand why you think of problems

.

.

I look up. The others are already halfway across the beach.

The girl lingers, her reedy frame draped in a tattered white dress with a faded strawberry print, a rounded collar, and buttons up the backâthe kind of dress American girls wore in the 1950s with Mary Janes. She stares at me with her thin dress flapping in the wind.

I take her hand. We walk across the beach, squinting in the wind and pelting rain. I glance towards the lake and see another girl walking beside us. I'm not sure where she came from, but she must be my little friend's twin. I can't distinguish her features in the dark, but she wears an identical flimsy white dressâopen in the backâover her thin frame, and she has the same shaved head.

I offer her my other hand.

The rain is immediate and heavy. The instant drench of a monsoon washes over us. By the time we reach the narrow footpath that leads to the village, the others have disappeared completely.

My flip-flops slip and grasp at the mud.

I stop, lost. We've reached the main path, but everything is black and blurry with rain. I can't see two feet in front of me. I don't want to do this. I want to retreat to that familiar cocoon:

I'm an American. They won't touch me

. But then, the Mai Mai are a militia that attacked the UN. Took twenty-five foreigners hostage. It is one thing to stumble without warning across unidentified guys with guns; it's another to do so knowing who they really are. And it's quite another to know they are here, in the dark, in the rain, after they've seen me wagging my oversized camera around.

I'm an American. They won't touch me

. But then, the Mai Mai are a militia that attacked the UN. Took twenty-five foreigners hostage. It is one thing to stumble without warning across unidentified guys with guns; it's another to do so knowing who they really are. And it's quite another to know they are here, in the dark, in the rain, after they've seen me wagging my oversized camera around.

I'm still clasping two small, wet hands.

The girls continue ushering me forward. I'm at their mercy.

I take slow, hesitant steps. I imagine men with guns must be just beyond the blur, waiting. The girls walk in front, patiently guiding me. All I can see is the dim glow of their white dresses and their eyes peering back at me. Wide-eyed African angels.

A lantern appears in the distance and floats across the path, then disappears.

We follow in its direction.

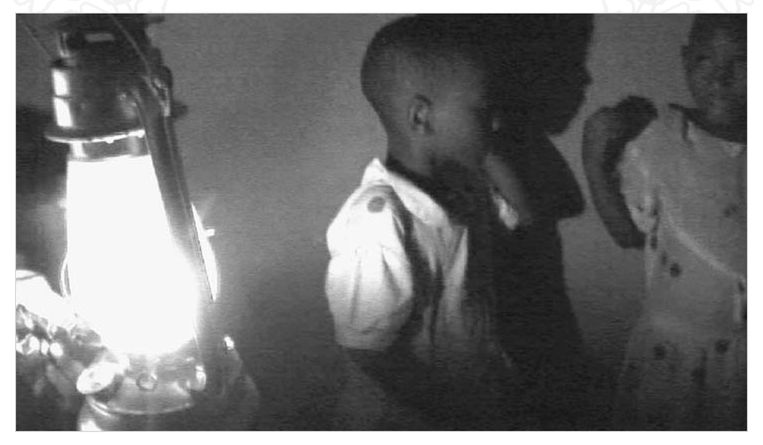

A wooden door opens and unseen hands shepherd us into a dim cement room. Maurice, Hortense, Kelly and a few villagers stand against the walls of a small storage room, weakly illuminated by a kerosene lantern that casts colossal

shadows around the corners of the space. The children stand next to me as the rain pounds the corrugated metal roof and leaks down the walls, pooling on the floor, making it impossible to sit down or lean against anything. We stand still and listen to the rain.

shadows around the corners of the space. The children stand next to me as the rain pounds the corrugated metal roof and leaks down the walls, pooling on the floor, making it impossible to sit down or lean against anything. We stand still and listen to the rain.

One of the girls inches towards me and stands close. I put my hand on her shoulder. Someone offers her a shawl. She lifts it to share, draping it around my shoulders. Am I comforting her or she is comforting me? I put the shawl back around the two children, patting their heads dry. We are waiting for the rain to subside, unsure of what is next.

But the rain continues to pour, with no signs of letting up. It feels like we've lingered here at least a half-hour. We make a mad dash outside, then run to another door. We settle into a living room, furnished with a few wooden benches, in a half-constructed cement house with no inhabitants. We dry off and the girls sit beside me. I can see their faces better by the kerosene lantern. I dig out my gift bags and divide stickers between the girls and another child. We plant big blue daisies on each other's faces, ignoring the world.

Kelly and I take underexposed snapshots of the room with our digital cameras, musing that the blurry, out-of-focus quality will give them a high-art vibe. The rain softens. An older woman comes to the door to collect the children. They go home for the night.

I would feel secure, cocooned away in this house, were it not for one problem. I need to pee. So does Kelly. The house has no toilet, so the nearest place to go is about a hundred yards away via the main path through the village.

I scramble through my bag and dig out the two flashlights Ted packed. One for Kelly, one for me. After all the resentment toward my Congo work and what it cost our relationship, he still meticulously packed my camera bag for every eventuality.

We step outside onto the empty mud path, still dripping from the rainstorm. My steps are quiet and self-conscious. I am trying not to think about the Mai Mai, or words like

exposure

or

bait.

It's like my dad used to tease me when I was a kid: Whatever you do, don't think about elephants. I try to steer

my thoughts away from calculating our risk factor in a village where 90 percent of the women have been raped. I fixate on the flashlights. They seem like the most romantic gift ever, making up for all the skipped birthdays and Valentine's Day presents. I feel the way I did after my first 24-mile training run, when I descended the last hill and saw him, my one-man cheering squad. This is love. We arrive at the outhouse on the remote edge of the village, backing onto fields and forest. I step inside. Its rough wooden slats go only as high as my shoulders. It is full of gaps and holes; mosquitoes are circling. Still, it feels like security. I turn off my flashlight and pee, imagining I'm invisible.

exposure

or

bait.

It's like my dad used to tease me when I was a kid: Whatever you do, don't think about elephants. I try to steer

my thoughts away from calculating our risk factor in a village where 90 percent of the women have been raped. I fixate on the flashlights. They seem like the most romantic gift ever, making up for all the skipped birthdays and Valentine's Day presents. I feel the way I did after my first 24-mile training run, when I descended the last hill and saw him, my one-man cheering squad. This is love. We arrive at the outhouse on the remote edge of the village, backing onto fields and forest. I step inside. Its rough wooden slats go only as high as my shoulders. It is full of gaps and holes; mosquitoes are circling. Still, it feels like security. I turn off my flashlight and pee, imagining I'm invisible.

When we return, we meet a man sitting in front of our hut, wearing rain boots and a slicker, a machete and ax at his side. Two men, husbands of program participants, have been assigned guard duty for the night.

Back inside, someone delivers foam pads for us. Somewhere in the village, a family is having a far-less-comfortable night's sleep because we are here. The run supports twelve families in this small village. Is that why we're getting special treatment? Or is this simply a Congolese welcome they would extend to any stranger stranded for the night?

We decide to sleep. I stretch a small cloth over the old foam pad, drape my sweater over my shoulders, and position myself for sleep. No one mentions the fact we wouldn't be here right now if I hadn't taken so long in the village earlier today. Instead, we listen to a squeaking bat climb around somewhere up above. Hortense assures us the animal is not inside with us. Kelly and I both know she's lying, but we prefer her version of the story and decide to go with it.

Listening to the bat squeak, I wonder what the protocol is when someone fails to return from a day-outing in Congo. I picture our UNHCR hosts filing through the buffet, lounging in the living room, nursing beers. Would they notice? Would someone say, “Where are those girls?” Would they make phone calls? I imagine the call to headquarters in D.C., or worse, to my mom, igniting hysteria: They didn't make it home.

“At least it will be a good story for the grandkids,” Kelly says from the opposite end of the room.

As though today's events weren't enough, I add in my best movie-trailer voice, “They clung to the tiny boat for their lives, as the gusty winds and waves threw them to and fro, bringing the young American girls ever-closer to the menacing rebel forces lurking beyond the peninsula's looming cliffs. . . .” We bust up laughing.

Yeah. We're fine. This is no big deal.

Yeah. We're fine. This is no big deal.

We spin embellished, melodramatic versions of the day's events, and Kelly and I laugh ourselves to sleep, or at least the pretense of sleep.

With my camera bag propped under my head like a pillow, I wait all night for the knock everyone in eastern Congo dreads: the knock of a militia outside your door.

In the middle of the night, I hear men's voices out front. I strain to hear. Someone is talking to the guards.

Who else would come calling at this hour? It must be the Mai Mai.

I brace myself, grasping the straps on my camera bag like the emergency strings on a parachute.

Who else would come calling at this hour? It must be the Mai Mai.

I brace myself, grasping the straps on my camera bag like the emergency strings on a parachute.

The voices disappear between intermittent rain and the foggy angst of an adrenaline-infused attempt at sleep. The knock never comes.

A soft, blue, early-morning light appears in the cracks under the door and around the windows. Hungry and edgy, I step out of the house. The guard still sits out front, awake. He's been up all night.

As I wipe my eyes, adjusting to the light, the Mai Mai I met yesterday, the one who wanted me to film him, saunters by with a Kalashnikov strapped to his back. He greets me with the casual air of a neighborhood shopkeeper.

“Muzungu, habari.”

“Muzungu, habari.”

White girl, good morning.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

The Long Drive Home

Other books

Stranger of Tempest: Book One of The God Fragments by Tom Lloyd

My Lord Rogue by Katherine Bone

The Coffey Files by Coffey, Joseph; Schmetterer, Jerry;

Werewolf Me by Amarinda Jones

Liverpool Miss by Forrester, Helen

Charlie's Heart: MC Romance (Burning Bastards MC Book 3) by Ryder Dane

Lone Star Valentine (McCabe Multiples) by Cathy Gillen Thacker

FALLING: The Negative Ion Series by Anthony, Ryanne

Good Behaviour by Molly Keane, Maggie O'Farrell