A Thousand Sisters (22 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

He stops to socialize with the aid workers already filling up the chairs nearby. I can't say why he catches my eye every time I scan the terrace. Or I catch mine catching his, leading to an exchange of glances that's a little too obvious for comfort. He is not my type. I've maintained a longtime preference for quirky, pensive, super-smart artists, so the regal, uberhandsome persona is like steak and eggs to a vegan. Not my thing. I dive back into my notes, trying to end this most-inappropriate man-interest. It's not on my Congo agenda.

The safari crew takes over the remaining chairs surrounding me, so I know he's not long behind. Within a few minutes, he joins his group in what I still choose to think of as my seating area. I try to concentrate on my notes, but

can't thanks to Mr. Wonderful's companion, a wild-haired, wild-eyed, bandanna-wearing fellow who seems to me like a modern incarnation of Henry Morton Stanley, the kind of bloodthirsty disaster tourist you might expect to land on the shores of Lake Kivu. He loudly drones on with manufactured sophistication, critiquing the cheap knock-off African masks sold at Orchid's front gate as though he's discussing the finest of wines. I give up. Abandoning my attempt to write, I pull out my earphones and interject myself into their conversation. “What brings you all to Congo?”

can't thanks to Mr. Wonderful's companion, a wild-haired, wild-eyed, bandanna-wearing fellow who seems to me like a modern incarnation of Henry Morton Stanley, the kind of bloodthirsty disaster tourist you might expect to land on the shores of Lake Kivu. He loudly drones on with manufactured sophistication, critiquing the cheap knock-off African masks sold at Orchid's front gate as though he's discussing the finest of wines. I give up. Abandoning my attempt to write, I pull out my earphones and interject myself into their conversation. “What brings you all to Congo?”

His companions fill in the blanks. They are a conservation group that's just spent the day in Kahuzi Biega Park. Though decked out in trekking gear and prepared for hours of off-trail bushwhacking in search of great apes, they stumbled across a gorilla after a ten-minute stroll. As I'm introduced to D, he makes it clear he is only tagging along on this group's trip; he is not part of their organization. He hands me his card: founder and CEO of an environmental nonprofit. His voice, with indistinguishable accent, seems so familiar. I'm convinced I know him. I must have heard him speak. Maybe in a video podcast from one of those global-ideas forums? He asks me to join them for dinner.

“That would be lovely,” I respond.

“Yes, that would be lovely,” he says.

Uh-oh.

We take a seat. D leans over at every opportunity, offering me his tomatoes and bread as we try to talk over Modern Stanley, who sits between us. Conversation turns to the subject of risk. D points to me as an example. “You see, Lisa, your being here in Congo is a major risk, but you must get something out of it. Something bigger than your potential regret for staying at home.”

D gets a call and excuses himself for a moment. Modern Stanley leans over to me, unable to conceal his pride as he informs me how truly Big, Important, and Rich their traveling companion is. He lists D's credentials: his stint teaching in the Ivy League, his role as founder and CEO of a multinational software corporation that serves half of the world's banks, the number of zeros in his bank account. Mr. Stanley's boasting makes me cringe with

embarrassmentâhe is grasping for status by osmosisâbut I am even more pained for D. Though we have never exchanged a private word, as D returns to his seat and briefly looks at me, his bulletproof persona seems transparent. I know what people say about him when he leaves the room. When I look into his eyes, the weight of isolation seems clearer to me than their color.

embarrassmentâhe is grasping for status by osmosisâbut I am even more pained for D. Though we have never exchanged a private word, as D returns to his seat and briefly looks at me, his bulletproof persona seems transparent. I know what people say about him when he leaves the room. When I look into his eyes, the weight of isolation seems clearer to me than their color.

He tells me about befriending malnourished kids in a village today. They were hungry, so he bought them eggs. Then more kids wanted eggs, so he bought eggs for them too. Then everyone wanted eggs. He bought every last egg the sellers had and before you know it, kids were laughing and eggs were flying, falling on the ground and cracking. Beautiful egg chaos. Here's a guy who would seem more in his element skiing in Vail or sailing the Mediterranean, but he's in Congo buying eggs for hungry kids. I think of his Egg Kids to my Peanut Girl, and I can't help but smile and remark, “That's the kind of thing I would do.”

Still, I do what any rational woman would do upon meeting an intriguing man in an exotic locale; I excuse myself and go back to my room. Sitting on the edge of my bed, I hold the phone in my hand. I contemplate a call to Ted to tell him about my night with the Mai Mai. I wonder if it is worth the leap.

I dial.

Long calls from the Congo to the United States would eat up all my phone card credits in no time, but they have special rates for calls from the States to the Congo. So if I want to talk to someone back home, I always ask them to call me back. Ted picks up, so I say, “Hey, can you call me back?”

I'm met with silence. Finally, with a distance far greater than any crackling phone line, Ted says flatly, “I'm working.”

All I can eke out is, “Oh.”

We are quiet for a long time.

In his English way, he cuts it off. “I need to get on and do.”

Â

THE NEXT DAY, I join D's group for dinner again as they go out on the town for their last night in Congo. We drive across Bukavu to a restaurant that sits

above the lake, sprawling and empty. In the old days this place must have been grand and happenin', complete with swimming pool, but tonight it is obvious those days are long past. We are the only group in the restaurant all night. The power goes out, leaving the worn room to be lit with dim, buzzing florescent lights powered by a generator; we wait two hours for curried mush. In the meantime, D gives a talk to the group, explaining his vision for future projects in Congo. As he returns to the seat next to me, he quips, “Now you know the truth. I'm just a glorified used-car salesman.”

above the lake, sprawling and empty. In the old days this place must have been grand and happenin', complete with swimming pool, but tonight it is obvious those days are long past. We are the only group in the restaurant all night. The power goes out, leaving the worn room to be lit with dim, buzzing florescent lights powered by a generator; we wait two hours for curried mush. In the meantime, D gives a talk to the group, explaining his vision for future projects in Congo. As he returns to the seat next to me, he quips, “Now you know the truth. I'm just a glorified used-car salesman.”

We talk with ease. He mentions he's heading to Zanzibar after they leave Congo tomorrow. With a vague recollection of flipping through Africa guidebooks many months ago, I say, “I meant to do something like that when I was here.”

“Why don't you join me?”

Run away to Zanzibar with a man I just met in Congo? I laugh.

Modern Stanley steers conversation towards the Mai Mai, making boisterous jokes about their strange rituals, from wearing sink-plug necklaces to raping farm animals. Tonight, even lighthearted mention of the Mai Mai makes me uptight. I squirm, then interrupt him, as if firing a warning shot. “I just had a campout with the Mai Mai.”

The table quiets down, perhaps due to my tense, shut-the-fââ-up delivery. Almost uncontrollably, I blurt out the whole story of my night on the peninsula. An uncomfortable silence settles over the table. D leans over the table, looks me in the eyes and says, “You're very brave.”

We sit next to each other on the ride home, cramped in the back of the SUV as it bounces and shifts along Bukavu's crumbling streets, around bends and past hills dotted with kerosene lanterns glowing on top of streetsellers' wooden crates.

With surprising insecurity, D asks, “Did you have a good time tonight?”

“Yes.”

“Really? You're sure?” His hand creeps over and touches my arm, then retreats.

“I had a great time.”

For the rest of the ride back to Orchid, he holds my hand.

I'm staying in a cottage on the far edge of the Orchid compound now and my nightly walk back to my room is creepy. So when D offers to walk with me, I don't hesitate to accept. His company is a comfort on the dark, lonely trek. We barely speak as we pass the guestrooms with armed men lurking out front, the gate marked PRIVATE: NO ENTRY, the Last Belgian's private porch, the ax-wielding security guy, guard dogs, and a hanging orchid garden. We arrive at my cottage, the last on the edge of the compound. The only barrier from the outside world is a rotting bamboo fence, with its own little terrace perched on a cliff above Lake Kivu. He kisses me.

The whole walk across the compound, I was thinking,

Whatever the question, the answer is yes.

So imagine my surprise when I hear myself telling him, “I need to say goodnight.”

Whatever the question, the answer is yes.

So imagine my surprise when I hear myself telling him, “I need to say goodnight.”

He launches a fresh campaign for me to join him in Zanzibar, but I decline.

A dog's rabid growl comes from behind the cottage. We scramble inside my room.

“It's dangerous for you to be here,” I say. “I like you more than any guy I've met in a long time.” I might be trying to convince myself as much as him as I offer reasons why he can't stay. “I'm just not a casual-hookup kind of girl.”

“I didn't think you were.”

Good answer.

I add, “It's just that I don't know you very well.”

“In fact, you don't know me at all,” he says. “You've only heard me give a speech.”

We look at each other for a moment, an unspoken exchange. What are the odds, the momentary chances in life? He doesn't push; he politely asks to trade numbers and leaves. I go to bed churning.

Did I really just dismiss him? Am I out of my mind?

Did I really just dismiss him? Am I out of my mind?

I don't see him again in Congo.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

Mama Congo

GENEROSE'S LANDLADY MEANT

every word of her threats. She has confiscated all of Generose's things and thrown the children out. They are scattered god-knows-where. With friends? Relatives? Generose doesn't know. She is distraught and dazed from the post-op medication when we briefly visit Panzi. My only comfort is a little secret. My mom has put out the word back home and we've raised US$1,500 to buy her a house. We say goodbye and head out to house-hunt.

every word of her threats. She has confiscated all of Generose's things and thrown the children out. They are scattered god-knows-where. With friends? Relatives? Generose doesn't know. She is distraught and dazed from the post-op medication when we briefly visit Panzi. My only comfort is a little secret. My mom has put out the word back home and we've raised US$1,500 to buy her a house. We say goodbye and head out to house-hunt.

Real estate shopping in Congo proves to be the strangest business experience I've ever had.

We start with the basics: Location, location, location. Maurice and I have brainstormed and narrowed our search down to the Panzi neighborhood, next to the Women for Women ceramics studio. Houses here should be in our price range, and Generose will already have welcoming friends and neighbors since several from her women's group live nearby. It's close to the hospital and, best of all, it is right next to a UN compound. As we get out of the car, I notice sandbag watchtowers on the periphery of the UN property, which overlooks a field and the neighborhoodâyou can't beat twenty-four-hour security. Maurice

asks around about houses for sale. After a few minutes we have a lead: a house for US$1,200.

asks around about houses for sale. After a few minutes we have a lead: a house for US$1,200.

We follow a narrow path away from the road. I'm already sure this place isn't going to workâGenerose can't navigate the path on crutches, especially the footbridge made of tree branches and tire rubber. But we will at least look for the sake of comparison shopping.

The little house with blue shutters sits in a tidy enclave of mud huts surrounded with gardens. We greet the owner, a woman about my age who's surrounded by a flock of young children who are just different enough in size to make me imagine this Mama has been nonstop pregnant for the past ten years. Maurice says, “They are selling because they do not have the means to survive.”

We duck inside and tour the dark, smoky cottage. In the living room, wood-framed couches draped with crocheted orange doilies, photo displays, and a tattered buffet give the place a make-do dignity that would make any Midwestern homemaker proud. The kitchen is filled with smoky pots and piles of ash. The bedrooms are simple.

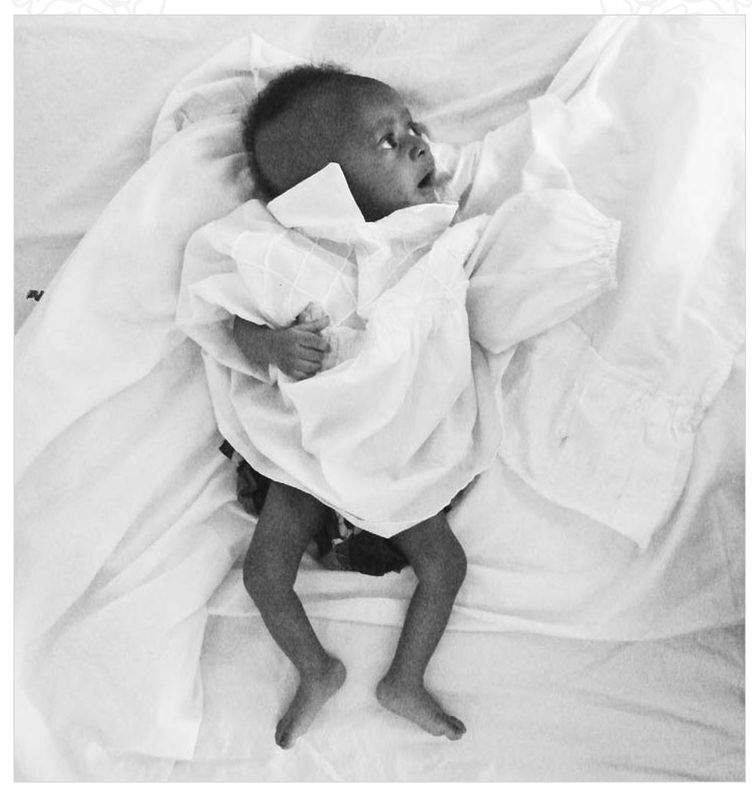

When I peek my head in the bedroom door, I barely notice a bundle of rags resting on the bed and a skinny, pale baby swaddled in them. I move to get a closer look at him. He's awake and quiet. Frail. But I know the look in his eyes, the way he's floating in and out; it's the familiar half-light of someone who is dying.

I feel the pull back to business, back to the hallway to talk with Mama about the house, to continue with the task of the day. It's sad, but it's not my problem. I'm busy enough today.

I look back at the baby.

It's like seeing a dog panting, sick and desperate, inside a sweltering car with the windows closed tight. You can look in at him and think, Well, it's none of my business . . . the owner will probably be back in a minute.

He's dying.

You can't save every baby in Africa.

Yeah, well, I'm not in the room with every baby in Africa. I'm in the room with this baby.

I have plans today.

I picture the identical scene playing out in suburban Minneapolis or Salt Lake City or San Diego, with a family going about their daily business unfazed while a baby is dying in the back bedroom. Unacceptable. Emergency.

But this is not the suburbs. It's Africa. It's the way things are, right?

I have plans.

I walk into the hallway and ask Mama, “Are you worried about the baby?”

“No, it's only the problem of illness.”

“What did the doctor say about the baby being so small?”

“The doctor didn't say anything.”

“That's a surprise,” I say. “Is it normal for Congolese babies to be that small?”

Maurice jumps in. “It is not normal.”

We move into the living room. His name is Bonjour. I rest him in my lap. He sweats, wearing a little polar fleece tracksuit. “Don't you think he's hot?” I ask Mama. Without waiting for permission, I peel off his pants, then his sweatshirt. It gets stuck on his head.

Other books

RUSH (Montgomery Men Book 1) by C.A. Harms

Vigil by V. J. Chambers

The Time Capsule by Lurlene McDaniel

Damia by Anne McCaffrey

The Unconventional Maiden by June Francis

Deadly Dues by Linda Kupecek

The Stag and Hen Weekend by Mike Gayle

The Bone Triangle by B. V. Larson

Dave at Night by Gail Carson Levine

Gravediggers by Christopher Krovatin