A Thousand Sisters (14 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“Do you remember the very first time you met Adrien?”

They argue with each other before Sifa answers. “He came just like a guest. He was hunting birds. When he went back to Europe, he came back the second time with a weapon. He started shooting elephants. The white

man was killing elephants and gave us meat, so we had to go in the village to Zairians, to exchange it for a cluster of bananas so we can also eat food like common people. Then he said the park had become his own property. He told us there was a potential war. That we would escape or we would be killed.

man was killing elephants and gave us meat, so we had to go in the village to Zairians, to exchange it for a cluster of bananas so we can also eat food like common people. Then he said the park had become his own property. He told us there was a potential war. That we would escape or we would be killed.

“He said he would look for another big piece of land where we would stay, so we would leave him the park. We left in 1972. Cecile already had two children. We crossed two big mountains to join the other people. Our grand-fathers and fathers died. They didn't see the land as promised.

“We came here. The Zairians refused for us to squeeze them. They wanted us to stay in the bushes. We were given this place to live.

“We beg you to help us so our voices can be heard by other people. Your presence helps us think we are remembered, that other people care about us. It raises our hope.”

I turn off the camera. I tell them about my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, George Harkins, who was chief of the Native American Choctaw tribe in 1831. At the time of the Trail of Tears, the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” abandoned their homelands and walked more than a hundred miles to newly formed reservations. My ancestor wrote a famous letter of protest. I describe it to Sifa and Cecile from memory in paraphrased shreds.

“We, as Choctaws, rather chose to suffer and be free than live under the degrading influence of laws, which our voice could not be heard in their formation. . . . We found ourselves like a benighted stranger, following false guides, until he was surrounded on every side, with fire and water. The fire was certain destruction, and a feeble hope was left him of escaping by water. A distant view of the opposite shore encourages the hope; to remain would be inevitable annihilation. Who would hesitate, or who would say that his plunging into the water was his own voluntary act? Painful in the extreme is the mandate of our expulsion. We regret that it should proceed from the mouth of our professed friend. . . . The

man who said that he would plant a stake and draw a line around us . . . was the first to say he could not guard the lines, and drew up the stake and wiped out all traces of the line. . . . Let us aloneâwe will not harm you, we want rest . . . and, when the hand of oppression is stretched against us, let me hope that a warning voice may be heard from every part of the United States, filling the mountains and valleys . . . and say stop, you have no power, we are the sovereign people, and our friends shall no more be disturbed.”

man who said that he would plant a stake and draw a line around us . . . was the first to say he could not guard the lines, and drew up the stake and wiped out all traces of the line. . . . Let us aloneâwe will not harm you, we want rest . . . and, when the hand of oppression is stretched against us, let me hope that a warning voice may be heard from every part of the United States, filling the mountains and valleys . . . and say stop, you have no power, we are the sovereign people, and our friends shall no more be disturbed.”

I can see their minds churning: This has happened before, they are thinking, in other places, to other people. They're curious. Trying to digest the new information, Sifa asks, “Were there Pygmies on this walk?”

“No.” I find a photo of a Tibetan woman that's saved on my camera and tell her, “Native Americans look a little more like her than like you or me. It's just that white people have behaved the same way all over the world. But then my great-great-great-great-great grandfather's daughter married a white man, then her child married a white person, then their child married a white person and so on. So now, I'm white. That was all before I was born. But you're not alone. In the United States, we did exactly the same thing to Native Americans: We gave them land surrounded with nothing, gave them nothing.”

Astonished, they nod emphatically. “It's just like we were treated.”

They study me for a moment, pensive.

Sifa adds, “It is as if we are the same.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

A Friend from Far Away

LIKE A BRIDE

on her wedding day, I peek out of the second-story window of the Women for Women office in Bukavu, watching fortheguests window of the Women for Women office in Bukavu, watching for the guests to arrive. Today is my first meeting with my sisters! As women trickle into the courtyard, I don't recognize anyone and I'm not sure I will, since all I have is a tiny photo of each of them. I return to the coffee table piled with bright green gift bags, each stuffed with carefully selected trinkets: stickers, sparkly pencils, balloons for the women's kids, pastel-colored plastic head-bands, little journals. I look to Maurice for reassurance. “Do you think the gifts are silly?”

on her wedding day, I peek out of the second-story window of the Women for Women office in Bukavu, watching fortheguests window of the Women for Women office in Bukavu, watching for the guests to arrive. Today is my first meeting with my sisters! As women trickle into the courtyard, I don't recognize anyone and I'm not sure I will, since all I have is a tiny photo of each of them. I return to the coffee table piled with bright green gift bags, each stuffed with carefully selected trinkets: stickers, sparkly pencils, balloons for the women's kids, pastel-colored plastic head-bands, little journals. I look to Maurice for reassurance. “Do you think the gifts are silly?”

“No,” he says. “It is only to show you are happy to meet them for the first time. You send them money every month, so they'll be happy.”

I get up and go back to the window again. Three women in the courtyard look at me, point, and wave.

“Is that them? Are they my sisters?”

“Yes,” a staff member says.

I can't wait. I rush downstairs to embrace them. Within a minute, I am surrounded by Women for Women participants, all getting in on the group

hugâeven though most are not my sisters! I give them each a warm embrace in honor of their sponsors who will never make it to Congo.

hugâeven though most are not my sisters! I give them each a warm embrace in honor of their sponsors who will never make it to Congo.

My sisters and I slip inside a meeting room. Much to my surprise, I recognize them all from their photos. We show each other the letters we've kept and together survey their sponsorship booklets, which contain passport-size cards that list their names, monthly slots where they sign for their money, and a line that reads, “Sponsor: Lisa Shannon/Run for Congo Women.”

The woman sitting next to me has a baby strapped to her back. “Who's your beautiful little one here?” I ask.

Maurice translates her answer. “When she bore the child, she was on the rolls here. She named her after you. The child's name is Lisa.”

I take the baby from her mom and hold her on my lap. This little Congolese Lisa was not named after me because of Run for Congo Women, but simply because I wrote her mom letters from America when she was pregnant.

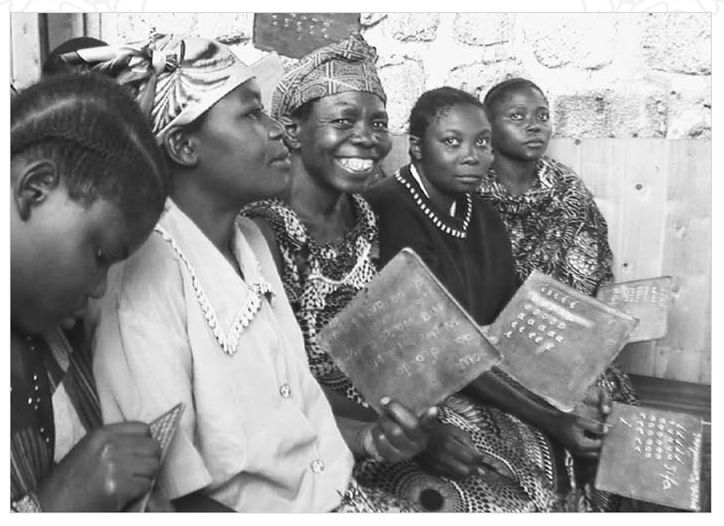

These twenty women have just finished the education part of the Women for Women program and await vocational skills training. They are all from Bukavu. The first sister introduces herself. “I became a seller of firewood, but the children were ill, so I spent all my money on medicine.”

I ask her, “So you had to stop selling wood, but now that they're better you can sell wood again?”

“Yes, I can start to sell wood again. If I have money. . . .”

“You have nothing left from your sponsorship funds?” I'm concerned, and it shows.

And so I've opened the door, setting the tone for the remainder of the meeting.

“With eight children, I was selling maize flour and wood. But now it's difficult after paying the hospital bill,” she says. “Now it is difficult selling wood also, because my children got ill. I paid sixty dollars and that was all the money I had. Now I have no income.”

Oddly, every sister seems to sell firewood or fish or clothes, and every

sister just spent her sixty dollars in graduation seed money on emergency medical care for her kids and can no longer work . . . unless she gets more seed money. Ugh. This is not what I was expecting to hear.

sister just spent her sixty dollars in graduation seed money on emergency medical care for her kids and can no longer work . . . unless she gets more seed money. Ugh. This is not what I was expecting to hear.

I'm sinking. As we go around the room, the conversation is all about angling for more money. I realize I've failed to meet a basic expectation. The term “American sponsor” seems to imply “unlimited source of cash.” But with more than two hundred sisters, I can't afford even five bucks each. I know it was naive to expect otherwise, but I did, even after one policy wonk in D.C. warned me, “Don't go there expecting it to be all sunshine and roses.”

Plus, corruption is baseline here. Suspicion is ubiquitous. The feeling that you're being ripped off is as inherent in the Congo as are women carrying loads. Why wouldn't it be? The Congolese people have been ruled in a nearly unbroken lineage of kleptocracy. After the Belgians left, in 1965, Mobutu Sese Seko, the quintessential corrupt African dictator, came into power. Mobutu siphoned off at least US$5 billion from Zaire into his personal coffers during his rule from 1965 until 1996. People here don't trust those with power or pass codes to big bank accounts. That includes charities.

The pervasiveness of suspicion here registered the other day when I had tea with Jean Paul, my friend from the UN. He leaned in close and announced, “I would love for you to expose Women for Women!”

Bewildered, I asked, “Expose them for what?”

“The sponsors send a hundred dollars each month. But the women only get ten dollars! It is being stolen! It's criminal!”

Jean Paul is wonderful; he's naturally passionate about his country and protective of his people. But I had to stop him right there. “No American sponsor sends US$100 per month to one sister. Women for Women is transparent about funds. Sponsors give twenty-seven dollars per month. Each sponsored woman gets ten, which is confirmed by signatures of two staff members and the participant. Then five dollars a month is put in a savings account, so that she gets sixty dollars when she graduates. The remaining money is used for her education, the letter exchange, and program costs. There are no secrets or intrigue.”

Jean Paul was quiet for a moment. I changed the subject and the conversation drifted to the Interahamwe, where he continued down that slippery slope of zero-credibility conspiracy theories. He claimed one of the top Interahamwe leaders was his good friend when they were both students in Rwanda. They stay in touch. While Jean Paul railed against the Chinese, I got the funny feeling he actually thinks the Interahamwe are A-OK. “The story of the Rwandan genocide as it is told is not what I saw,” he says.

If he is leading up to saying that the Interahamwe are the victims of the Rwandan genocide, well, I'm not joining him for a stroll down that country lane. I cut the meeting short. The next morning, I ask Maurice, “Is Jean Paul sympathetic to the Interahamwe?”

“Yes, Lisa. Very sympathetic.”

Sweet.

So I've hired the brother of an Interahamwe-sympathizing Women for Women hater. I'm off to a great start. . . .

So I've hired the brother of an Interahamwe-sympathizing Women for Women hater. I'm off to a great start. . . .

I'm taking nothing for granted, so I decide to keep an eye on Maurice, to make sure he's not showing any bias.

Â

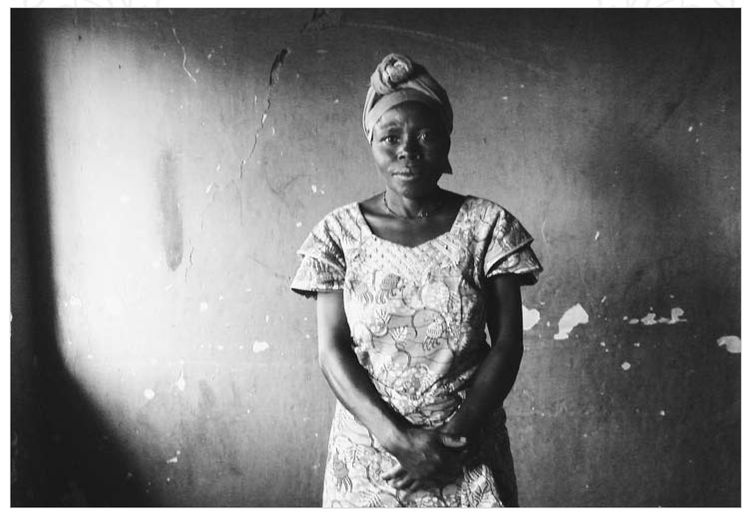

A SISTER, FURAHA, slips into our meeting late, the last to arrive. She hasn't picked up on the tone of the meeting, the cues to join the campaign for more cash. She begins to talk, but starts weeping. “I came from Ninja, a village eighty kilometers from Bukavu. They killed most of my family. It was done monthlyâone month they come and kill some members, another month they come and kill other members. The last member was killed in November, three months ago.”

“Furaha,” Maurice says, noting the irony in her expression of devastation. “In Swahili, it means joy.”

I had imagined that presenting gifts bagsâmostly for my sisters' childrenâwould be a fun, lighthearted moment. But I feel only dread as I drag out the green gift-sacks adorned with stickers, cringing as I make excuses. “I wish I had more to give you.”

They smile and dance with gratitude. I give each of them a big hug and we say goodbye.

I ask the four sisters that my mother is sponsoring to stay after the meeting. We call my mom in America at two in the morning, her time. She picks up, foggy but delighted. We put each of her sisters on the line; in an awkward attempt to connect, they speak into the language-barrier void. Maurice steps in to translate. A heavyset, earthy grandma, who looks remarkably like my mother, takes the phone. She repeats something emphatically, keeping it clear and basic with one word. Maurice does not translate. I ask what she's saying.

He translates, “Money! Send more money!”

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

My Own Private Sister

I HAVE A

confession to make. During the first year my first sister Therese was in the program, I did not write her. I was so busy running and speaking and trying to build a movement, I let it slide. Maybe it was because I had only received one letter from her. Maybe it was because I assumed the important part was putting a check in the mail. Maybe I just didn't know what to say. Since I've been in Congo, I've learned that the assumption “They don't care if I write” is dead wrong. In my spare moments, waiting in the Women for Women courtyard, I regularly find myself surrounded by participants who dig out plastic pouches from around their necks or under their blouses that are stuffed with letters from their American sisters. They shove their sponsorship booklets and letters my way, asking, “Do you know my sister?”

confession to make. During the first year my first sister Therese was in the program, I did not write her. I was so busy running and speaking and trying to build a movement, I let it slide. Maybe it was because I had only received one letter from her. Maybe it was because I assumed the important part was putting a check in the mail. Maybe I just didn't know what to say. Since I've been in Congo, I've learned that the assumption “They don't care if I write” is dead wrong. In my spare moments, waiting in the Women for Women courtyard, I regularly find myself surrounded by participants who dig out plastic pouches from around their necks or under their blouses that are stuffed with letters from their American sisters. They shove their sponsorship booklets and letters my way, asking, “Do you know my sister?”

Other books

Soul Deep by Pamela Clare

Trapping a Duchess by Michele Bekemeyer

Ever Unknown by Charlotte Stein

The Murder of a Queen Bee by Meera Lester

The Vanishers by Heidi Julavits

A Wreath Of Roses by Elizabeth Taylor

La Matriz del Infierno by Marcos Aguinis

The Tweedie Passion by Helen Susan Swift

Contagious by Emily Goodwin

Hard to Be Good (Hard Ink #3.5) by Laura Kaye