A Thousand Sisters (33 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“What was his name?”

“Lucien.”

“And your husband?”

“Claude.”

“How did you meet your husband?” I ask.

“My husband was ill, and he came to the hospital where I was a nurse. In treating him, the love began between us. I loved him first because he was handsome. Second, because he gave me advice. After the treatment, he left the hospital, but after two days, he came back to visit me. In one week, he came back with his father to bring a hen as a sign of thanks. After that, he began the habit of visiting. He did this for two years. After two years, he decided to come see my parents.

“There was a great ceremony. My husband's family brought my parents two cows and six goats. We went to the priest so he could bless us. Afterward, we organized a big party.”

“What was he like as a person, a man, a husband?” I ask.

“The type of husband I dreamed of since I was a child. Someone very tall, who's not a drunk and doesn't smoke. When I met him, he had all these qualities, and I said, âThis is the man.'

“As a husband, he was responsible. As the father of my children, he was responsible up to the end of his life. He had a habit. When I was very tired he would say, âToday, it is not your chore. I will prepare food for the whole family. ' He prepared eggs and rice. That was his dish. This created a problem with his family. They said, âHow can a man prepare food for his wife? This must be a problem of witchcraft.'

“But there was no witchcraft. Only love.

“We say when you love one another very much, you don't have a long life. Sometimes I have candidates, men who come and would like me to be with them, but when I remember the love my husband had for me and I know those men have their own wives, I say, âNo. You can't give me love as given by my husband. You only want to joke with me. No. No.'”

“I have one last question,” I tell her. It has been on my mind for a year. “My father didn't die in a violent way. He had cancer. But when I think of him, the first thing that comes to mind is the way he would slowly run his finger around the edge of his coffee cup while we would talk for hours. I miss that.” His habit used to annoy me when he was alive. But when I think of it now, I remember it like the slow hum of a Tibetan singing prayer bowl. “What do you miss about your husband?”

She doesn't hesitate. “When I was pregnant, very heavy with a baby, my husband would wash my body. It was very intimate.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

Salt

WHY?

THAT'S THE

burning question I've had for years.

THAT'S THE

burning question I've had for years.

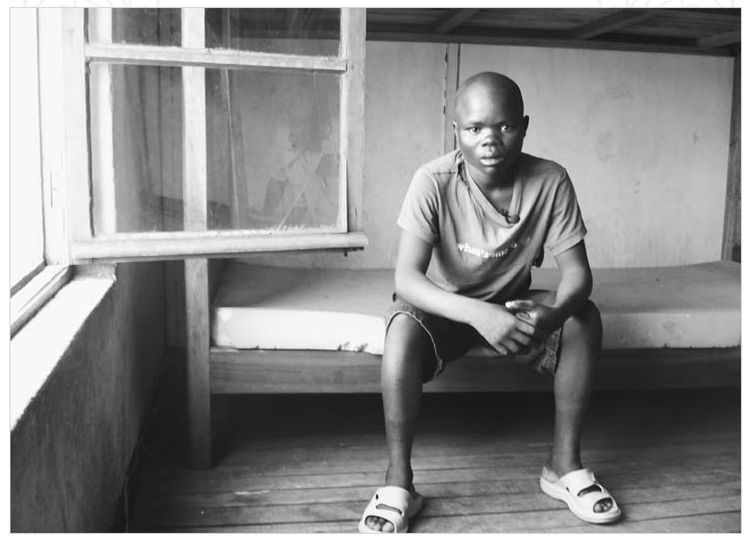

I have a unique opportunity to talk with one of the very few people who might have the answer. I'm sitting down with a former Interahamwe rebel who is staying at the child soldier rehabilitation center. André walks into the empty boys' dorm, which is lined with wooden bunk beds and barred windows. I'm surprised. He is a chubby-cheeked seventeen-year-old in jeans and a T-shirtâand he's Congolese. He carries himself with the mild, respectful manner common to boys who have been through serious military training.

In 2002, André was at school when the Interahamwe showed up to “recruit.” They forcibly took every boy in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. He was eleven years old.

André lived as a member of the Interahamwe for six years. “Life in the forest was very, very hard,” he tells me. “It was not possible to wash with soap. We had to eat food without salt. It was impossible to eat food prepared in pans, to have clothes. We had hair everywhere on our bodies. We ate tree roots. We passed many years without seeing anyone in society.”

I ask, “If Interahamwe rebels could have normal lives once they leave the militia, how many would simply walk away?”

“If you leave, you are killed. If there was really a possibility, if they had authorization to go home, maybe eighty out of a hundred would accept. Easily.”

For a boy who never finished fifth grade, he is as close to the mark as any Washington policy wonk. Those I have spoken to estimate would-be Interahamwe deserters at around 70 percent.

“The other twentyâwhy would they stay?” I ask.

“The twenty are afraid of judgment. They recognize they have killed a lot of people in Rwanda. One person may have killed more than a hundred persons in Rwanda, so they say, âInstead of going back to my country, I prefer to shoot myself and die here in the forest.'”

The Interahamwe are responsible for the most sadistic violence in Eastern Congo. But perhaps worse, this force of six to eight thousand provides the excuse for other militias to existâand terrorizeâin the name of protecting civilians from the Interahamwe. The combined presence of these militias has cost 5.4 million mostly innocent civilian lives. But how many die-hard Rwandan

genocidaires

lead the militia, while effectively holding their fellow FDLR combatants hostage? I'm not often shocked, but I'm skin-burning astonished when I learn

fewer than one hundred

set the agenda, and in turn, fuel instability throughout Eastern Congo and by extension central Africa

.

genocidaires

lead the militia, while effectively holding their fellow FDLR combatants hostage? I'm not often shocked, but I'm skin-burning astonished when I learn

fewer than one hundred

set the agenda, and in turn, fuel instability throughout Eastern Congo and by extension central Africa

.

Fifteen years into this mess and the international community still has no plan to deal with the Interahamwe.

But there's still something I don't get. I ask André, “Why kill the villagers? Why torture them? One woman I know, they cut off her leg and fed it to her children. They cut out villagers' eyes or nose. Why? What's the logic?”

André bites his lip. “What you heard about, it is true. This is only to show the hard conditions in which the Interahamwe live. Even a child of ten years oldâor lessâwas raped. I saw with my own eyes victims of cuttingâbreasts, nose, mouth. It is only to show the Interahamwe are no longer persons like us. They are like animals.”

“It's because Interahamwe are bitter for being stuck in the forest?” I ask. “It's like revenge on humanity?”

“That's it. A kind of revenge. How can some people spend a good life when others spend a bad life in the forest?”

“How many people do you think you've killed?” I ask him.

“When we talk in terms of killing, I was under orders. We were sent to ask for money. To ask for salt. Because salt was precious. Whenever you do not have salt and you do not give us money, I have orders to kill you. And really, I killed.”

Because salt was precious.

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

The Hidden Face

ALEJANDRO GREETS US

anxiously. He has been calling around, trying to track down the only UN guy who was stationed here in Kaniola at the time of the massacre. But it's turned out there is no such person; none of the foreign UN officials stationed in Walungu at that time is still in Congo. So Alejandro has taken the initiative of asking local UN staffers if they know anything about it. Frankly, I'm not sure it's worth the effort. I'm only looking for a few details that weren't included in the report, plus the names of anyone affected. Alejandro has run into another roadblock. “Everyone is acting very strange. Even the cleaning lady, when I ask her, is like this.” He imitates her by hemming and hawing, avoiding our eyes. No one will talk.

anxiously. He has been calling around, trying to track down the only UN guy who was stationed here in Kaniola at the time of the massacre. But it's turned out there is no such person; none of the foreign UN officials stationed in Walungu at that time is still in Congo. So Alejandro has taken the initiative of asking local UN staffers if they know anything about it. Frankly, I'm not sure it's worth the effort. I'm only looking for a few details that weren't included in the report, plus the names of anyone affected. Alejandro has run into another roadblock. “Everyone is acting very strange. Even the cleaning lady, when I ask her, is like this.” He imitates her by hemming and hawing, avoiding our eyes. No one will talk.

“Of course, I want to help you,” he says. “But now I want to know why everyone is acting this way!”

Alejandro calls for another UN staff member, Joseph. He is a short local man, reserved and precise, who speaks better English than almost any Congolese person I've met. He worked closely with Major Vikram and Major Kaycee. I chat him up about Major Vikram, mentioning the emails we exchanged about that day. Joseph is evasive. “I think I remember something like that in 2005.”

“No, this was in May.”

“I don't know. Talk with others maybe.”

“If Major Kaycee and Major Vikram went to the site of that attack, you would have gone with them,” I say. “Right?”

“I would go with them, of course.”

“Surely if you were there, if you saw seventeen dead bodies, you would remember, wouldn't you?”

“Maybe,” he answers. “I don't remember when exactly. Maybe if you look at the daily security reports. . . .”

When did this turn into an interrogation scene? I didn't come here looking for intrigue. I just want to know if the people I met that day are okay. “I don't understand why this is so secret. It was an international news story. So what's the big deal? I just want a few more details about what happened.”

“Do you have clearance?” Joseph asks.

“Of course,” I tell him. “The Pakistani Battalion is taking us to Kaniola.”

Alejandro jumps in. “I have told you, you are free to talk with them.”

Joseph sticks to his guns. “Do you have

written

permission?”

written

permission?”

“No,” I fess up.

Alejandro pushes him. “You are free! Help these people help your country!”

Joseph is growing frustrated. “Look at the report. I think you will find . . . especially in that spotâ”

Alejandro cuts him off. “Yes, but as we say in my country, these are cold words. You are a living, breathing person! You were there!”

Poised to burst, Joseph spits out, “I have plenty to say.”

He reins himself in, retreating to a more officious tone. “Read the report and you can ask me questions.”

The UN doesn't turn over the report. It's classified.

Â

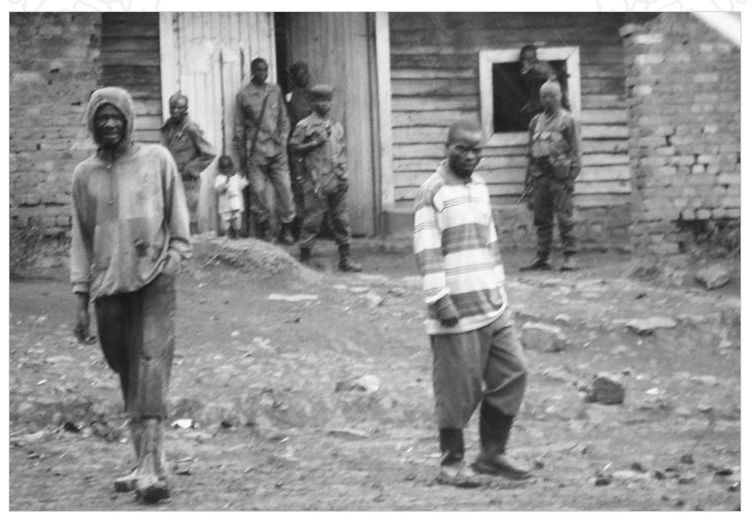

WE GO TO Women for Women's Walungu center, where a few participants from Kaniola agree to talk with us. “The family with seventeen people killed are my neighbors,” says a young woman with a red dress and cornrows. “The

Interahamwe came, started cutting people, killing them and burning houses. We spent the night here in Walungu. In the morning we went back to Kaniola. There were government soldiers there already. We felt safe and remained. They were burning dead bodies.”

Interahamwe came, started cutting people, killing them and burning houses. We spent the night here in Walungu. In the morning we went back to Kaniola. There were government soldiers there already. We felt safe and remained. They were burning dead bodies.”

“You saw that?”

“Yes.”

“When was the last attack in Kaniola?”

Another woman offers, “February, when they took my two nieces.”

They're all in agreement. It's been three months since the last attack. And that's actually an improvement, compared to the twice-weekly attacks that were happening before.

“It's the government's Commander X who masters security in Kaniola,” someone says. “Whenever he's there, nobody dares attack because he is strong. When he goes to Bukavu to visit his family, attacks happen.”

I present my white binder, as though I'm conducting a one-woman war tribunal and each blurry, pixilated eight-by-ten video print will immortalize its subject. They crowd around the white notebook, flipping page by page, looking at their friends and neighbors. It might be a silly exercise. Watching them scan the pages, I realize that I have no idea what I want to

do

with my notebook full of fuzzy video printouts. I just need to know.

do

with my notebook full of fuzzy video printouts. I just need to know.

“Do you know that little boy?”

They shake their heads.

“I know four of the children,” another woman says. “The militia killed their grandfather.”

“What about these little girls?” I ask.

“

I recognize that one,” another woman answers. “They got into her compound, killed her father, and burned people in the house next door. Burned them alive. About a year ago.”

I recognize that one,” another woman answers. “They got into her compound, killed her father, and burned people in the house next door. Burned them alive. About a year ago.”

They point to a photo of a man on the roadside, waiting next to the children with the plastic water tubs. “He disappeared. It's as if he was killed. His sister went a year ago to the bushes for sex slavery.”

“This one died,” a woman says, pointing at another man. “The Interahamwe killed him nine months ago.”

The women gather in closer. They are pointing at someone, discussing her among themselves. It's the first woman I passed on my Sunday walk in Kaniola; she was on her way to church. She wore a beautiful dress and had pretty hair and makeup.

Other books

Havok: A Bad Boy Mafia Romance by Riley Rollins

There Is No Otherwise by Ardin Lalui

Final Scream by Brookover, David

A Family Reunited by Jennifer Johnson

Eternal Melody by Anisa Claire West

The Boys Start the War by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor

An Earl Like No Other by Wilma Counts

The Ice King by Dean, Dinah

Homespun Bride by Jillian Hart

Rose by Jill Marie Landis