A Very Expensive Poison (7 page)

Read A Very Expensive Poison Online

Authors: Luke Harding

Zakayev was the main emissary abroad of the Chechen republic of Ichkeria. By this point Ichkeria no longer existed: Russian troops had recaptured Grozny. Like Litvinenko, Zakayev was a noxious figure for the Russian government, which accused him of terrorism. By the end of the decade most of Chechnya’s independent leaders had been wiped out; Zakayev was the last man standing.

As well as Zakayev, Litvinenko became friends with a curious Italian called Mario Scaramella. Scaramella was the secretary to an Italian parliamentary commission that investigated links between Italian politicians and the KGB. Set up in 2002, the Mitrokhin Commission was politically motivated – an attempt by Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right government to smear its enemies, in particular the former and future centre-left prime minister Romano Prodi.

Scaramella claimed that Prodi was a KGB operative. To support this controversial thesis he fed fake documents to Litvinenko in London. Litvinenko certified them as genuine. Whether he did this because he believed them or simply because he was paid to do so, we don’t know. Perhaps it was a combination of both factors. In fact, the Mitrokhin archive itself – based on notes made by a KGB defector – was more damning about other Italian officials at the Moscow embassy, who came out of the investigation far worse. (There was no evidence Prodi was ever KGB, but plenty showing Italian diplomats in Moscow falling into honeytraps and scrapes.)

This was a murky business indeed. Litvinenko was apparently trading in compromising material, for which

there is always a ready market in Russia, known as

kompromat

.

Some of Litvinenko’s campaign work struck his friends as a little loopy. He blamed the 7/7 bombings – a series of coordinated bomb attacks in central London, carried out in 2005 by four British Islamist men – on the FSB. He also wrote in an article for the

Chechenpress

website that Putin was a paedophile. The incident that inspired it was certainly somewhat bizarre: the president, encountering a group of tourists in the Kremlin, pulled up the shirt of a small boy and kissed him on the tummy. Still, as Goldfarb observed: ‘Putin is probably not a paedophile.’ To Litvinenko’s critics the article was further proof of his sheer public wildness.

Asked later if Litvinenko was a bit of a conspiracy theorist, Goldfarb added: ‘Well, at the time I thought so, but with what has happened since, I have become a conspiracy theorist myself, so it’s very hard to judge.’

In July 2006, the Duma rushed through two new laws that seemed to have a direct bearing on Litvinenko. The new legislation allowed Russia’s spy agencies to eliminate ‘extremists’ anywhere abroad, including in the UK. The definition of ‘extremism’ was also expanded. It now included ‘libellous’ statements about Putin’s administration.

Bukovsky and Oleg Gordievsky – the former KGB colonel turned high-profile MI6 informant – understood perfectly what these changes meant: that state murder in western countries now had official cover. In a letter to

The Times

, they wrote: ‘Thus, the stage is set for any critic of

Putin’s regime here, especially those campaigning against Russian genocide in Chechnya, to have an appointment with a poison-tipped umbrella. According to a statement by the Russian defence minister Sergei Ivanov, the blacklist of potential targets is already compiled.’

Russia was about to host the G8 summit in St Petersburg. Western leaders should be prepared ‘to share responsibility for these murders’ or not go, Bukovsky and Gordievsky wrote. Needless to say, there was no boycott.

Litvinenko’s activities in exile were multifarious: campaigner, journalist, security consultant, investigator. In London he gave interviews and attended public meetings. The common thread that linked these personas was Litvinenko’s hatred of Putin, the man who had put him in jail, and of the FSB. He was the Russian president’s most persistent and ebullient critic.

One important activity, however, remained hidden.

*

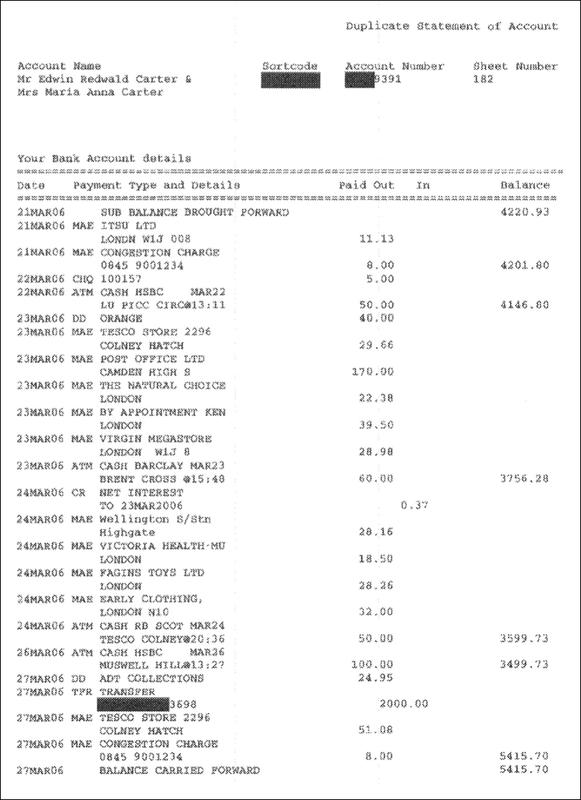

The bank entries speak of middle-class normality. Shopping trips to Waitrose and Sainsbury’s, direct debits for Sky Digital, and London’s congestion charge. The account is with HSBC. Its holders are ‘Mr Edwin Redwald Carter & Mrs Maria Anna Carter’. The balance in 2006 fluctuates between £969.02 and £8,076.36. The Carters don’t appear to be especially well-off. Nor are they broke.

In fact, Litvinenko’s bank statements tell us a lot. They give a picture of a typical, health-conscious family (purchases from The Natural Choice), with one child and a car. The Litvinenkos were living at 140 Osier Crescent, a terraced house of yellow brick with a small balcony and

a parking spot. The modern estate is in Muswell Hill, in the north London borough of Haringey.

The bank statements root the Litvinenkos in their area. There are debits of £5.40 from Transport for London in East Finchley and Highgate – Litvinenko’s regular off-peak travel-card. Visits too to The Children’s Bookshop in Muswell Hill. And Japanese food: Yo! Sushi at Gatwick Airport and Itsu, Litvinenko’s favourite restaurant in Piccadilly Circus. The odd small sum of money comes in from time to time – a £75 payment from the David Lloyd centre, where Marina taught a kids’ class in ballroom dancing.

One regular credit entry is unusual, though.

On the 26th of each month, Litvinenko received an anonymous payment. It appears on the statement simply as ‘Transfer’, from an unnamed bank account. The account ends with the digits ‘3698’. The sum in sterling is always the same: ‘2000.00’. The paying organisation appears – one might think – to be rather bashful.

The sum of £2,000 found in among the groceries and trips to Tesco came from the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), also known as MI6.

British intelligence didn’t recruit Litvinenko in Moscow. Nor was he ever a spy in Russia: his career in the KGB and FSB involved detective work against criminals, not intelligence. When he arrived in the UK at the end of 2000 seeking political asylum, Litvinenko told Home Office officials truthfully: ‘I didn’t work in intelligence and I didn’t work against England.’ He added: ‘I have as yet had nothing to do with British intelligence.’

According to Marina Litvinenko and Alex Goldfarb, Litvinenko began working for MI6 in 2003, some two years after he fled to London. The secret service agency put him on its payroll the next year. In Britain, he was never a full-time agent.

Instead, Litvinenko worked for the agency as an expert adviser. MI6 consulted him on Russian organised crime in Europe, with Litvinenko travelling to various European countries, especially Spain, but also to the Baltic states, Italy and Georgia, assisting their law-enforcement efforts. He spent more time away on ‘business trips’. He continued his journalistic work but kept a lower profile.

In line with its long-standing policy, the British government has neither confirmed nor denied that Litvinenko was an MI6 employee. Its file on Litvinenko hasn’t been made public. We don’t know who hired him. Or if Sir John Scarlett – MI6’s prickly then chief, known by the initial ‘C’ – ever perused Litvinenko’s personnel record.

Scarlett knew about Moscow agents. He had been involved in the operation to recruit Gordievsky, the UK’s most prized defector. Scarlett was fluent in Russian and lived in Moscow in the 1970s. In 1994, Scarlett, by this point Moscow station chief, was expelled from Russia in a political row.

Marina Litvinenko says she knew of her husband’s undercover job. After all, she says, how else might Alexander explain the mysterious £2,000-a-month payments? She didn’t know details. She was uncertain if Litvinenko worked for MI5 or MI6, the numbers a source of confusion.

MI6 gave Litvinenko the tools of the trade. He got a British passport for trips abroad – not in his name, of course, but under an as-yet-unrevealed pseudonym. MI6 also assigned him a handler, codename ‘Martin’, and he was given a dedicated encrypted phone for calling him. Since Litvinenko’s English was spotty, ‘Martin’ was almost certainly a Russian-speaker.

The pair would typically meet in coffee shops in London’s West End, including in the basement of the Waterstone’s bookshop in Piccadilly – an inconspicuous spot for a rendezvous, with a backdrop of novels and historical biographies. ‘Martin’ drank coffee; Litvinenko ate pastries. A Russian oligarch, Alexander Mamut, later bought the Waterstone’s chain and launched a dedicated Russian-language section upstairs.

According to Goldfarb, MI6 spies were nice guys – a procession of well-bred Johns and Tims. Goldfarb, an expert microbiologist, says MI6 contacted him in 2003. The agency wanted to know if Iraq’s Saddam Hussein had biological weapons. He didn’t know. He met the spooks in a Piccadilly branch of Caffè Nero.

What did Litvinenko do for MI6? Litvinenko had spent ten years investigating the Russian mafia and its links with Kremlin officials, including Putin. He knew names, faces, backstories. Goldfarb says Litvinenko asked him to translate the ‘Uzbek File’, which features as a chapter in his book

The Gang from the Lubyanka.

The Blair government’s take on Russia was increasingly negative, but framed through the prism of Putin’s rollback of civil society and democracy. This was

something new – apparent evidence of how crime lords and politicians conspired to send Afghan drugs to European capitals via St Petersburg. One of those allegedly involved, directly and indirectly, was Putin. Litvinenko writes: ‘As an operative officer I have well-founded suspicions regarding Mr Putin – that he is a member of this gang.’

Like all foreign spy agencies, MI6 has a network of agents in the field. It also relies on electronic intelligence, supplied by the UK government’s monitoring station, GCHQ, in Cheltenham, and passed to government ‘customers’. In addition, the UK is part of Five Eyes, a spying alliance encompassing the US and its National Security Agency (NSA), Canada, Australia and New Zealand. It’s probable that Litvinenko reviewed intercept material gleaned from eavesdropping operations against mafia targets. Marina Litvinenko says her husband identified individuals who featured in surveillance photographs.

In Moscow, former FSB colleagues claimed Litvinenko revealed the names of Russian ‘sleeper agents’ in the UK to MI6 – another act, from the Kremlin’s viewpoint, of treason. This seems fantastical. Litvinenko never worked in Russian intelligence. So it’s unlikely he would have known the identities of undeclared Russian spies, living long-term in Britain, the US and elsewhere.

Litvinenko’s attitude towards spying appears pragmatic rather than romantic. The tradecraft didn’t interest him much. He was also very discreet. Litvinenko was frequently in contact with Scaramella, the Italian, while

helping the Mitrokhin Commission in Rome. Scaramella asked Litvinenko repeatedly if he was a British agent.

Litvinenko told Scotland Yard later: ‘During all our initial meetings he always, insistently, importunately, asked every day whether I was working for MI5 and MI6. He was the only person who asked me so often about it. I told him, Mario, what difference does it make for you? I said, you know, if I say yes you’ll think I’m an idiot because such things like this are not spoken about. And if I say no, you won’t believe me.’

Litvinenko denied he was working for British intelligence, telling Scaramella: ‘I have played spies in my life up to here. And the main thing is, I write books, why would they need me? Think yourself.’

Litvinenko’s consultancy work for Her Majesty’s Government threw up two important questions. Neither has been properly answered.

One, did the Kremlin discover that Litvinenko worked for MI6?

Two, did MI6 consider Litvinenko to be at risk from Moscow’s assassins? If not, why?

*

In addition to his work for MI6, Litvinenko began in 2005 to provide regular information to Spain’s intelligence services. In fact it was British intelligence that introduced Litvinenko to its Spanish counterpart. The Spanish security service assigned Litvinenko a Russianspeaking handler named ‘Jorge’. The £2,000-a-month retainer paid by MI6 also covered Litvinenko’s work with Spanish spooks and Spanish prosecutors. With

increasing frequency, Litvinenko began flying to Madrid and Barcelona. Marina said her husband would return from his trips to Spain with presents – a Real Madrid T-shirt, porcelain souvenirs. As an undercover spy he flew business class, on one occasion even managing to get the autograph of David Beckham, a fellow passenger, for his son Anatoly. But his reason for being in Spain was far from frivolous.

The Spanish authorities were at the time grappling with a serious and chronic problem. From the mid-1990s onwards,

vory v zakone

– in Russian, thieves in law – began to enter Spain.

Vor v zakone

was the highest rank in Russian organised crime. Spain provided a useful haven for Russian mafia bosses, as a base for operations, and a territory safer than Russia itself. Their influence grew. Their activities in Russia included contract killings, kidnappings, drug-running, prostitution and arms-smuggling. Profits in Russia, including from illegal casinos, were laundered in Spain and invested in real estate.

In 2004, Spanish prosecutors created a formal strategy to ‘behead’ the Russian mafia.