A Very Expensive Poison (8 page)

Read A Very Expensive Poison Online

Authors: Luke Harding

The biggest group active in Spain was the Tambov gang, the same St Petersburg outfit that Litvinenko investigated in the 1990s as an FSB officer. It also included Alexander Malyshev, once the Tambov’s competitor, and now its Spain-based criminal partner. The authorities began extensive investigations. They discovered the mafia had no known jobs or sources of income but were living in lavish mansions. The cash clearly came from money-laundering. The challenge was to prove this.

According to the Spanish daily

El Pais

, Litvinenko provided information on top mafia figures. They were Vitaly Izguilov, Zakhar Kalashov and Tariel Oniani. In the early 1990s, Litvinenko’s FSB department had investigated Oniani, a Georgian-born Russian citizen, in connection with a string of kidnappings. One of its victims was the chairman of the Bank of Russia. The case against Oniani was dropped after Litvinenko got a call from above ordering him not to touch him. Kalashov was a hit man. He, too, enjoyed protection from official Russian structures.

Spanish security officials launched two major operations against the Russian mafia, codenamed Avispa (2005–7) and Troika (2008–9). The first phase of Avispa in 2005 saw the arrest of twenty-eight people, twenty-two of them alleged thieves in law. Litvinenko provided the Spanish with details of locations, roles and activities of gang members. The Spanish hailed the operation as the biggest ever undertaken against a global mafia network.

In reality, the results were somewhat mixed. The biggest targets – Kalashov and Oniani – both managed to escape the country on the eve of the raids following a tip-off, most probably from the Russian security services or a corrupt Spanish official. Kalashov was arrested in Dubai in 2006 and extradited to Spain. His fortune, according to court documents, was €200 million.

A secret diplomatic cable, leaked in 2010, and sent from the US embassy in Madrid, suggests that Litvinenko was key to these Spanish operations. His main contribution

was to untangle the intimate links between the Russian mafia, senior political figures and the FSB. They were, in effect, a single criminal entity.

In January 2010, Jose Grinda Gonzalez, a special prosecutor for corruption and organised crime, met with US officials in Madrid. In a ‘detailed, frank’ briefing to a new US–Spain counter-terrorism group, Grinda said that the mafia exercised tremendous sway over the global economy. He said that Russia, Belarus and Chechnya had become ‘virtual “mafia states”’ and predicted that Ukraine – under its new Kremlin-backed president Viktor Yanukovych – was ‘going to be one’.

The special prosecutor said it was an ‘unanswered question’ whether Putin was personally implicated in the Russian mafia and whether he controls its actions.

The leaked cable reads: ‘Grinda cited a “thesis” by Alexander Litvinenko … that the Russian intelligence and security services – Grinda cites the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and military intelligence (GRU) – control organised crime in Russia. Grinda stated that he believes this thesis to be accurate.’

There was evidence that certain Russian political parties operate ‘hand in hand’ with the mafia, the prosecutor said. This evidence came from the intelligence services, witnesses and phone taps. He said that the KGB and its successors created the ultra-nationalist Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR), which is home ‘to many serious criminals’. He also claimed there were ties between politicians, organised crime and arms trafficking.

According to Grinda, organised criminals in Russia ‘complement state structures’, with Moscow employing the mafia to do whatever the ‘government of Russia cannot acceptably do as a government’. He said that Russian military intelligence, for example, used Kalashov to sell arms to the Kurds, with the aim of destabilising Turkey.

Grinda added: ‘The FSB is absorbing the Russian mafia but they can also eliminate them in two ways: by killing organised crime leaders who do not do what the security services want them to do, or by putting them behind bars to eliminate them as a competitor for influence. The crime lords can also be put in jail for their own protection.’

The evidence collected by Spanish investigators would lead to the arrest in 2008 of Gennady Petrov, the Tambov gang’s alleged boss; his number two, Alexander Malyshev; and Izguilov. Leaks to the Spanish press talked of the ‘hair-raising’ contents of wire-tapped conversations. In them, senior mafia figures boasted of their connections with Russian government ministers to ‘assure partners that their illicit deals would proceed as planned’.

*

It wasn’t until 2015 that the names of some of these ministers were revealed. Grinda, together with a colleague Juan Carrau, presented a 488-page complaint to Spain’s Central Court. The petition brought together ten years of investigative work against the Russian mafia.

According to the news agency Bloomberg, which got hold of the petition, Petrov had his own top-level government network in Moscow. It features many of Putin’s

allies. They include Viktor Zubkov, Russia’s prime minister between 2007 and 2008 and the chairman of Gazprom, the natural gas extractor and one of the world’s largest companies. Zubkov’s son-in-law Anatoly Serdyukov, Russia’s former defence minister, also features.

Other officials mentioned as being ‘directly related’ to the alleged gang leader are deputy prime minister Dmitry Kozak and Alexander Bastrykin, who studied law with Putin in Leningrad. Bastrykin is the head of Russia’s investigative committee that opens (and shuts) major criminal cases. It was Petrov who allegedly secured Bastrykin’s appointment. One other name is Leonid Reiman, a former communications minister.

Putin appears three times, including in a 2007 conversation between two Tambov operatives. (They are discussing a house in the Alicante region – and say that Putin owns a neighbouring property in nearby Torrevieja. Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s press spokesman, describes this as ‘nonsense’.)

The most intriguing name is that of Nikolai Aulov. Aulov is deputy chief at Russia’s Federal Narcotics Service. His boss is none other than Viktor Ivanov, the politician and former KGB officer who had the ear of Putin and who was the subject of Litvinenko’s 2006 report. The dossier logs seventy-eight phone calls between Aulov and Petrov and describes Aulov as ‘one of the most important persons for Petrov’. In 2008, the petition says, Petrov asked an associate to get Aulov to put pressure on Russia’s new customs chief. The mafia boss wanted to facilitate port shipments for his group.

The court document seeks to charge twenty-seven people, including Vladimir Reznik, a deputy in Putin’s ruling United Russia party and chair of the Duma’s financial markets committee. Petrov was spotted on the island of Mallorca with Reznik. Spanish police raided Reznik’s Mallorca mansion, allegedly a gift from the gangmaster.

It was an extraordinary picture – mobsters and ministers; money-washing and gun-running; the Kremlin not so much a government as a well-entrenched international crime group with truly big ambitions.

The accused Russian politicians deny wrongdoing. Reznik told Bloomberg his relationship with Petrov is ‘purely social’. Meanwhile, Spain’s prosecution of Russian mafia suspects ran into various legal snafus. The suspects would hire Spain’s best lawyers; often they got bail. The strategy to behead them, though, was working.

All of this was thanks to Litvinenko. He made clear to ‘Jorge’ that he was willing to testify in court against Putin and Ivanov, spilling everything he knew about Putin’s alleged links with the Tambov gang.

This would be some court case. And enough reason for powerful people in Moscow to want Litvinenko silenced.

‘Are you guys from the KGB?’

AUSTRALIAN HOTEL GUEST TO LUGOVOI AND KOVTUN, 17 OCTOBER 2006

There is something surreal about Mayfair. It is London’s wealthiest district, a dark-blue square on the Monopoly board and home to successive influxes of the international super-rich. Arabs rich from oil, Greek shipping tycoons, African dictators – all find a home here, washed in by a global tide of credit crises, coups and recessions.

In Mayfair’s Hanover Square, boys and girls in red uniforms play games at the end of the school day, among plane trees and an exotic palm from the Canary Islands. It’s all rather English pastoral. The girls sport straw boaters. Around the square are boutiques, florists, a library and pigeons; nannies chatting in Russian sit on park benches.

North of the square you find Grosvenor Street and a row of fashionable eighteenth-century Georgian townhouses. This was once the abode of earls, lords, admirals and the odd poet. Now there are the understated brass plaques of commerce. It’s not entirely clear what many of the businesses based here do. Hedge funds? Corporate

PR? Wealth management? The location radiates prestige, reliability, trustworthiness.

And a little mystery. If London is the spy capital of the world, Mayfair is its centre. It is the traditional home of private intelligence companies. There are casinos, luxury car showrooms and exclusive nightclubs. Nearby is Pall Mall. Here, in gentlemen’s clubs, the establishment comes together. Defence officials, spooks and ministers meet to do deals and exchange gossip. The Houses of Parliament are down the road.

Most of those who work in private intelligence have at some point been on the other side. They include exspies, army officers and former Scotland Yard detectives – sometimes ones prepared to bend the law.

Their work includes providing business intelligence, investigating employee fraud and supplying personal protection. Another lucrative market is due diligence. Companies looking to expand internationally need information on prospective partners, especially in jurisdictions with lousy records of governance, like Africa, the Middle East and the ex-Soviet Union.

Litvinenko visited Grosvenor Street often. He would arrive here on foot, walking past the Bentleys, Porsches and Ferraris, before disappearing into an entrance with an ornate classical portico and heavy oak front door. This was 25 Grosvenor Street. On the fourth floor were two companies, Titon and Erinys. Both were bespoke intelligence firms. They operated in the commercial market but also had links – never quite defined – with the world of British spying.

When Litvinenko first fled to Britain, Berezovsky was paying him a salary of $6,000 a month. The money came from Berezovsky’s New York-based International Civil Liberties Foundation. It was reduced in 2003 and again in 2006. Berezovsky told police there was nothing malicious about these cuts. They were done by mutual agreement, he said, as Litvinenko became more ‘independent’, and started working for British and Spanish intelligence.

Litvinenko was understandably upset as his income fell. And, according to Goldfarb, ‘a little bit worried’ about his financial future. He was forced to seek other sources of income. He’d hoped that MI6 might give him a full-time job. It didn’t.

The agency did, though, introduce Litvinenko to Dean Attew, Titon’s director. It asked Attew if he might help Litvinenko to develop a commercial footprint. Litvinenko would conduct investigations into Russians who were of interest to clients. In return he’d get a fee.

Litvinenko knew about the Russian mafia and therefore had something to offer Titon. He also had one good source in Moscow. This was the investigative journalist and prominent Putin critic Anna Politkovskaya. Politkovskaya visited the UK often – her sister lives in London. She would bring Litvinenko news of the latest Kremlin intrigues. Some of Litvinenko’s other contacts were in jail (like former FSB-officer-turned-lawyer Trepashkin) or out of date.

What he needed was a Russian partner. In 2005, Litvinenko had what appeared to be a piece of luck. Andrei

Lugovoi – at that time a successful Moscow-based businessman – rang him up. They had first met in 1995, when both had loosely been members of Berezovsky’s circle.

On 21 October 2005, Litvinenko had dinner with Lugovoi in a Chinese restaurant in Soho. Lugovoi said he had flown in for a match between Chelsea and Spartak Moscow. He brought someone with him: a pensioned-off Russian intelligence officer. The officer was a technical expert whose job was to place special microphones in foreign embassies and official buildings. His name remains unknown.

Recalling their conversation, Litvinenko said that forty minutes into the meal Lugovoi made him an interesting offer: ‘Alexander, if you like to work with me we can earn money together.’

Litvinenko could take orders from London-based companies seeking to do business in Russia, Lugovoi said. Back in Moscow, Lugovoi would collect sensitive information. They would be a team, a sort of mini-version of the New York-based corporate investigations and risk consultancy firm Kroll. They would make money. Litvinenko said: ‘Thank you, thank you.’

Litvinenko’s first foray into this industry with his new partner was with a company called RISC Management, run by a former Scotland Yard detective called Keith Hunter. It offered ‘security investigations and services’. Hunter specialised in Russian clients, one of them Berezovsky. Litvinenko was asked to investigate Russia’s deputy agriculture minister on behalf of a vodka company. Was the minister corrupt?

The money wasn’t huge, but Litvinenko found these corporate assignments interesting; his new colleagues good people. Increasingly, Lugovoi flew to London. The intelligence product he brought with him, as his part of the arrangement, was uninspiring. His work on the vodka assignment appeared to have been culled from the Russian internet.

Still, RISC paid $7,500 to Lugovoi’s Cyprus bank account. Lugovoi was ex-KGB, which meant a lot in Putin’s Russia. Maybe Lugovoi was the key that would prise open the door to Gazprom and other state giants.

In January 2006, Litvinenko, his Chechen friend and neighbour Zakayev, and their wives, were guests at Berezovsky’s sixtieth birthday party. It was a lavish black-tie affair held at Blenheim Palace, the ancestral home of the Duke of Marlborough near Woodstock in Oxfordshire. Lugovoi flew in from Moscow. They

shared a table and posed together for a photo in front of the palace’s entrance of classical columns. Lugovoi, standing on the left of the picture, is an ingenuous presence, his smile as ever disarming. It was the only time that Marina Litvinenko met Lugovoi.

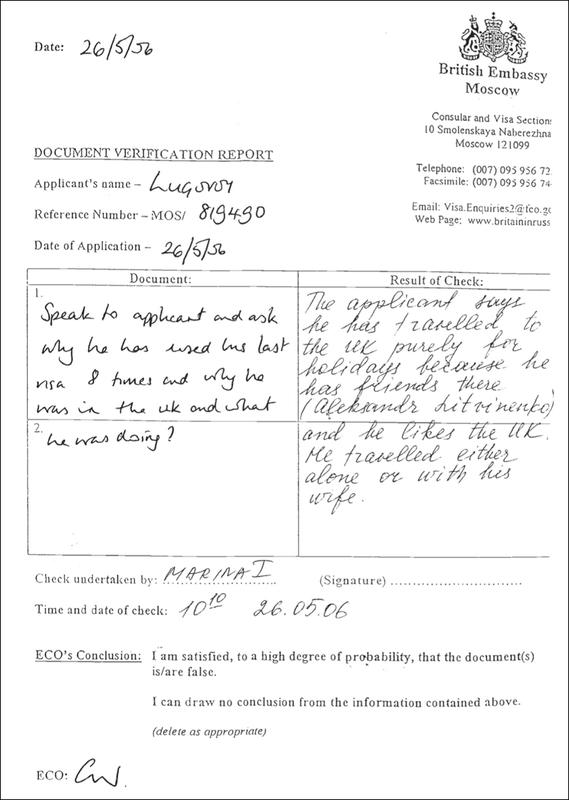

Lugovoi flew back to the UK in March, April (twice) and May (twice) and June. He was a man of means who stayed in the best hotels – in Knightsbridge, Mayfair, Piccadilly. The trips were so frequent they aroused mild suspicion. A British consular official in Moscow noted on his visa application: ‘Speak to applicant and ask why he has used his last visa eight times and why he was in the UK and what he was doing?’

Another embassy official noted Lugovoi’s reply: ‘The applicant says he has travelled to the UK purely for holidays because he has friends there (Alexander Litvinenko) and he likes the UK. He travelled either alone or with his wife.’ Lugovoi’s passport is a galaxy of Russian exit and UK entry stamps – Stansted Airport, 22 January 2006, Gatwick, 5 April 2006.

Meanwhile, Litvinenko’s dealings with Berezovsky were cooling. The dispute was over money. There was no terminal quarrel. Berezovsky continued to pay Anatoly’s private school fees, and said of Litvinenko: ‘We continued good relations.’

Litvinenko’s relationship with Lugovoi, however, continued to grow – what had started as a business alliance apparently developing into friendship. Over the summer, Lugovoi and his wife Svetlana visited Litvinenko at his home in Muswell Hill. On the walls Lugovoi saw photos

of Litvinenko with Bukovsky and Oleg Gordievsky, the former KGB colonel and station chief in London who famously defected to Britain in 1985. All three were prominent Putin enemies.

Litvinenko introduced Lugovoi to his circle of contacts, including Titon’s director Attew. The meeting took place at Heathrow Airport’s terminal one, while Lugovoi was on his way back from Canada to Moscow. Attew disliked him intensely: ‘Seven years of watching people around gaming tables and reading body language left me feeling extremely uncomfortable when I sat with Lugovoi. I didn’t enjoy the experience and was very pleased to be leaving there.’

Attew’s own status was a matter of sensitivity. Lugovoi would later claim that Attew was Litvinenko’s handler and an MI6 agent. And that Attew had tried – unsuccessfully – to recruit him as an asset for British intelligence. MI6 have not, of course, confirmed or denied this but it would not be unlikely that Attew was a former spook and he was certainly well connected in that world.

Soon after the Heathrow meeting, something very odd happened at 25 Grosvenor Street. In the early hours of the morning intruders broke down the black oak front door. They ignored the immediate offices and went to the fourth floor, taking out the entire door-frame to the Titon vestibule. They spent four or five minutes inside. Seemingly they stole nothing.

The next day Attew made a thorough search. No clues. ‘In my business, that’s a reconnaissance,’ he said. ‘That’s a recce.’ At the time Attew didn’t connect it with Litvinenko. Later the break-in made gruesome sense.

The job was done by professional agents. This was the FSB, almost certainly, scoping the ground for a future operation. Litvinenko had always warned Berezovsky that he was most at risk from people who’d featured in his past. In his keenness to make money, and to provide for his family, Litvinenko had forgotten his own rule.

*

It was a warm autumn day when the two Russian visitors arrived in Grosvenor Street. That morning, 16 October 2006, their undercover mission had almost met with failure when DC Scott, the customs officer, stopped them at Gatwick Airport. But their cover story had held up. Most importantly, the costly poison they had been given back in Russia was intact. This was polonium, a rare and highly radioactive substance. It is probably the most toxic substance known to man when swallowed or inhaled – more than 100 billion times more deadly than hydrogen cyanide.

The next task was to deploy it. They had come to poison Litvinenko.

Scotland Yard would never establish how Lugovoi and Kovtun carried the polonium into Britain. The amounts involved were very small and easy to disguise. There were several possibilities: a container with the poison administered by a pipette-style dropper. Or an aerosol-like spray. Even a modified fountain pen would do the trick. Within its container the polonium was safe. Out of it it was highly dangerous. Ingested, you were dead.

Lugovoi and Kovtun, it would become apparent, had no idea what they were carrying. Their behaviour

in Britain was idiotic verging on suicidal. Nobody in Moscow appears to have told them Po-210 had intensely radioactive properties. Or that it left a trace – placing them in specific locations and indicating, via telltale alpha radiation markings, who sat where. It was possible to identify anything and everything they touched: door handles, telephones, wash basins.

These clueless assassins left numerous trails. The most vivid was radiation: subsequently tested by forensic experts, and turned by experts from the Metropolitan Police into colourful three-dimensional graphics. Another was financial: a series of clues whenever Lugovoi paid a bill with his Bank Metropol Mastercard. One other was cellular. Phone records, retrieved by detectives, showed who called whom, for how long, and when.

And of course there were witnesses. They told a remarkable story: of two killers who, in addition to the business of murder, indulged in sight-seeing, shopping, boozing, fine dining – and flirting. During their trips to London they tried to pick up women. Without success. Surely, the KGB was better at seduction in its heyday?