A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (108 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Grant tried to limit their potential for disaster by giving Butler and Sigel mere supporting roles in his spring campaign. Their objective would be to deprive the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia of its supplies, while Grant went after Lee himself. “Beast” Butler started out first on May 3 with 30,000 soldiers, along with their horses and heavy guns, crammed into an assortment of steamboats and ferries for the two-day journey up the James River toward Richmond. As there was only a light smattering of Confederates forces south of Richmond, there was no reason why Butler could not disembark his army at one of the many landings along the river and march unmolested all the way to the capital. Grant wanted Butler to plant his forces just below Richmond, blocking every route from the south and west. If Butler had been acting solely at his own discretion, Grant might have worried. But two veteran commanders had been appointed as Butler’s subordinates to prevent him from wrecking the venture.

The 5th Battery, New Jersey Artillery, containing the English private James Horrocks, was among the units placed under Butler’s command. When Horrocks saw Butler in person he was startled by his notorious ugliness. “Imagine a bloated-looking bladder of lard,” he wrote to his parents. “Call before your mental vision a sack full of muck … and then imagine four enormous German sausages fixed to the extremities of the sack in lieu of arms and legs.”

45

Butler had been ordered to drive hard toward Richmond, smashing the rail link between Petersburg and Richmond as he went. But Horrocks did not notice any particular sense of urgency after his regiment arrived on May 5 at a deserted City Point, less than twenty-five miles from the Confederate capital.

The day was warm and sunny, far too pleasant to waste idling on the banks. “I took a walk with another fellow,” wrote Horrocks. “We passed several little shanties, and at every one the soldiers … were ransacking and taking everything worth taking.” Horrocks and his friend hurried on. “We walked on about a mile and a half and then came to a fine residence of a planter, in which about a dozen soldiers were making free with everything.” As they approached the gate, a couple of soldiers came out laden with struggling livestock. A headless lamb was slung over the shoulder of one, its neck still dripping with blood. The gray-haired owner of the house sat hunched on the doorstep, moaning as Horrocks stepped around him. Once inside, he heard screams and the crashing of wood as soldiers forced open every door and cupboard. The black house servants were cowering in the corner of the parlor while the elderly wife of the owner shouted hoarsely at the men to leave. Horrocks walked down the hall to escape the noise. “In the next room, which was extremely well furnished, was a piano. I sat down and played Home, Sweet Home! with variations.” The playing soothed him, and without another thought, he joined in the looting. “I took a flute and a package of beautiful wax candles and a piece of scented soap.” He also found a wad of Confederate notes, which he was about to pocket when the old lady entered the room and shamed him into putting them back. Suddenly, Horrocks wished to slip away as quickly as possible.

The troops were starting to move out when Horrocks returned to the landing place. No one had missed him. They marched for several hours through thick piney woods. “Every now and then we passed some poor fellow who had given out and lay on the side of the road with his knapsack and musket alongside of him and then we passed portions of their kit … scores of blankets and overcoats, and boots and shoes.” Like Frederick Farr, these men had been left behind, “thrown away,” in Horrocks’s words, “in order to lighten the load.”

46

Horrocks promised his parents that he would take the greatest care with his life; he expected to be fired at soon and was curious how it would feel. “When I have felt it, I will tell you how it is.”

47

Horrocks’s eagerness to encounter Confederate bullets was delayed by General Butler, who, instead of blocking the approaches to Richmond from the south and west, had become diverted by the nonexistent need to build fortifications and trenches, giving the Confederates enough time to insert General Beauregard’s small force of 18,000 men between the Union Army of the James and the capital. Butler’s failure to reach Richmond meant that Grant would be setting his spring campaign into motion with his plan damaged from the outset.

The Army of the Potomac began moving on May 4. If Grant’s ultimate objective was to reach Richmond, Lee’s was just as straightforward: to hold down the enemy long enough to convince the Northern public to vote for a pro-peace president in the November election. He was relieved when his scouts confirmed that the Federals had crossed the Rapidan River and were marching along the Germanna Plank Road. The route Grant had chosen passed through the Wilderness, whose dense wasteland had helped to give the Confederates their victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Instead of marching quickly through the Wilderness, the Federal commanders took a leisurely pace, so that by midnight the advance of the army was still less than halfway through. In the darkness, there was many a startled yell as an accidental kick or stumble over a mound of leaves revealed human remains beneath. Many soldiers were too frightened to sleep that night, but not the new volunteer James Pendlebury, who lay down on the ground curled up like a dog. Pendlebury had made the beginner’s mistake of throwing away his knapsack during the hot and tiring march. “In throwing away the knapsack I also threw away my cartridge box,” he wrote. During the night, his captain “came and wakened me with his foot, and, handing me a cartridge box, said, ‘Here take that, and don’t ask any questions.’ He had stolen it from one of the other men because he was so fond of me.”

48

Pendlebury’s regiment was part of General Hancock’s II Corps, one of the first to enter the Wilderness on May 4. There was no possibility he would be able to hide from the fighting once it began. “This was my first battle and I can’t say that I was a brave man, for I wished I was at home,” he wrote in his memoir. “But after I had fired a few times I began to get accustomed to the work and soon I had no fear about me.” His baptism started at 4:00

P.M.

on May 5. Lee had succeeded in placing two of his three corps inside the Wilderness even though General Longstreet was still a day’s march away. Forty thousand Confederates pitched into seventy thousand Federals. Just as Lee had hoped, the Union regiments lost their sense of direction, firing wildly into the trees and charging hither and thither. At sunset many soldiers had no idea where they were and resorted to lying behind improvised breastworks. There was nothing to see except the outlines of tree trunks. But the noises coming from the woods were terrifying. As at Chancellorsville, stray sparks lit the dry underbrush, and fires spread along the forest floor, burning everything in their path.

Yet neither army flinched. At dawn on the sixth the fighting resumed with the same ferocity. Under General Hancock’s direction, Pendlebury’s corps suddenly found its cohesion and began to overpower the Confederates. Lee was near the Orange Plank Road when he saw hundreds of troops running toward him. Realizing that the line had broken, he spurred his horse forward in a desperate attempt to rally the men himself. At that moment, the first of Longstreet’s regiments—a brigade of Texans—came storming up, having marched through the night from the Old Fredericksburg Road. The sight of Lee caused them to shout in dismay, “Lee to the rear! Lee to the rear!”

49

The Texans rushed ahead of him; but of the eight hundred who went forward, only three hundred returned unhurt.

Longstreet’s corps had tramped through little-used tracks, taking every shortcut no matter how snarled and wild in order to reach Lee, the boom of gunfire spurring them on when exhaustion threatened. Captain Francis Dawson, who had passed his artillery examination in April, was exhilarated despite his arduous ride. “You know that until I left I had never been in the saddle in my life,” he wrote to his parents, “but in sober truth the saddle is the headquarters of a staff officer and by dint of long practice you cannot fail, however stupid, to become moderately expert.”

50

Dawson was riding with Longstreet and his staff when Lee met them. Displaying none of the hesitancy that had undermined his leadership at Knoxville, Longstreet saw immediately that the woods could aid them if he ignored conventional tactics and allowed the terrain to dictate the formation of his battle line.

51

His troops ran forward, with Longstreet and his staff, including Dawson, riding ahead of the surge.

The breastworks of the Irish Brigade caught fire under the barrage of artillery, scorching some of James Pendlebury’s comrades, but the flames protected them from being overrun by the Confederate charge. But other Federal regiments turned and ran. The 79th Highlanders had been positioned at the rear of the line by General Hancock. “You have done your share,” the general told Ebenezer Wells. Relieved to be spared a fight, the Highlanders were dumbfounded when they were ordered to beat the fleeing regiments back into line. “Our men bayoneted a few,” recalled Wells, “and others of us not liking to do so to our own men, knocked them down with the butt end of the rifles.”

52

The 79th could not prevent a general rout, however, and by late morning the Orange Plank Road belonged to the Confederates. Longstreet had smashed the Federal line with a panache that recalled Stonewall Jackson’s stunning victory the previous May at Chancellorsville. Dawson trotted up behind Longstreet as the general led a small group of staff and commanders along the road. The Confederates were congratulating one another on their signal success.

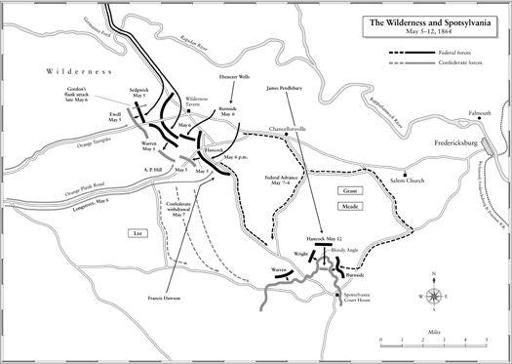

Map.19

The Wilderness and Spotsylvania, May 5–12, 1864

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Though it was a date few liked to remember, it was exactly a year and a day since General Jackson had been accidentally shot while scouting three miles farther west, near the Orange Turnpike Road. The Orange Plank Road was similarly hemmed in by trees, which made it difficult for the isolated pockets of Confederate troops on either side to see one another. “There were but about eight of us together, all mounted,” described Dawson. “

Without a moment’s warning

one of our brigades about 2000 strong, only 50 or 60 yards distants [

sic

] poured a deliberate fire into us.” “Friends,” shouted one of Longstreet’s officers, too late. Seconds later, four of the eight were on the ground. Three were dead or dying; Longstreet was slumped over his saddle, choking and coughing up blood. Dawson and two others lifted him from his horse and carried him over to a large tree. “My next thought was to obtain a surgeon,” continued Dawson, “and, hurriedly mentioning my purpose, I mounted my horse and rode in desperate haste to the nearest field hospital. Giving the sad news to the first surgeon I could find, I made him jump on my horse, and bade him, for Heaven’s sake, ride as rapidly as he could to the front where Longstreet was. I followed afoot.”

53

Dawson arrived as Longstreet was being carefully laid in an ambulance. The general had been hit by a single bullet, which passed through his neck and out his right shoulder. He was bleeding heavily but conscious. Dawson joined the silent group riding in the ambulance. They met Lee on the way to the hospital. “I shall not soon forget the sadness in his face,” wrote Dawson, “and the almost despairing movement of his hands, when he was told that Longstreet had fallen.” Longstreet’s appearance convinced Lee that the Wilderness had claimed his other most reliable commander. Visibly shaken, he rode away to assume control of Longstreet’s attack. But Lee could only guess what Longstreet had planned to do, and not all of it made sense to him. It was four o’clock when he gave the order to attack, several hours after Longstreet had intended his final assault to begin. During the delay, the Federals had regrouped and were prepared for the onslaught. The firing ceased at nightfall with neither side conceding their ground.

The following day, May 7, saw skirmishes but no real fighting. The two armies needed time to replenish their ammunition, fill places left by the dead and wounded, and eat and sleep after two days of continuous fighting. In the past forty-eight hours, 11,000 Confederate and 17,500 Federal soldiers had been killed or wounded in the Wilderness. Troops in the Army of the Potomac watched with a baleful eye as the supply wagons were hitched to horses and led toward the rear. They took it as a sign that Grant had ordered a retreat, just like Hooker after Chancellorsville and Burnside after Fredericksburg. The casualties from the battle were certainly enough to make most commanders unwilling to risk another clash with Lee; but Grant was different from his predecessors. The wagons were moving because Grant was continuing the advance to Richmond. He informed General Meade that the entire army must be on the march by midnight. Once the long lines began moving, Grant took his place at the front so that the men would know he was leading them toward, rather than away from, battle.